Egypt’s former President Hosni Mubarak is scheduled to face trial on 3 August on charges of corruption and the killing of protesters during the 18-day uprising that led to his ouster. As the prosecution and a public hungry for justice prepare for what may be Egypt’s trial of the century, there is much to learn from recent examples of deposed leaders around the world, from Indonesia to Romania to Taiwan.

Perhaps the most relevant case is that of Suharto, Indonesia’s dictator of 32 years who ruled the country with a brutal combination of oppression and corruption.

Like Mubarak, Suharto’s family enjoyed great political and economic influence and manipulated public money. The family's wealth was estimated at about US$16 billion, even as, near the end of his presidency, an economic crisis hit Indonesia.

In 1998, Suharto's economic policies were rejected by Indonesians. The same year, he re-elected himself president for the seventh time in a row.

Strikes spread around the country. University students took to the streets and announced civil disobedience. Thousands besieged the parliament in Jakarta, calling for Suharto to step down.

Like their Egyptian counterparts 13 years later, Indonesian revolutionaries did not end their demands with Suharto’s resignation. The people kept demanding that Suharto and his family face trial on charges of corruption and seizure of public money.

Suharto was remanded to trial but citing the former dictator’s "deteriorating health," it was postponed several times. He died in 2008 at the age of 87 without ever facing trial.

These days in Egypt, the possibility of a repeat of the Suharto situation looks strikingly plausible. While Mubarak’s sons are already in prison, the former president is being detained in a hospital in the Sinai resort town of Sharm el-Sheikh due to his "deteriorating health."

Egypt's most well-known touristic city is currently witnessing protests to push the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF) to transfer Mubarak to the prison's hospital or to a military hospital outside Sharm el-Sheikh, condemning the negative effect of his presence on tourism in the city.

In Romania, the situation was different. Nicolae Ceausescu ruled the country with an iron fist for 15 years. The Romanian people, with the support of the army, revolted against him in 1989, shortly after the fall of the Berlin Wall in nearby Germany.

Ceausescu fled with his wife, but the couple were pursued, caught and put to military trial. Both received death sentences after the fastest trial of a dictator during the 20th century.

The trial was broadcast on Romanian state television to assure people that Ceausescu and his wife were killed. The masses came out and destroyed statues of Ceausescu in the streets of Bucharest. In 2010, Romanian authorities exhumed Ceausescu and his wife’s remains to confirm their identities at the request of Ceausescu's family.

Mubarak could potentially face the death penalty for his role in ordering the killing of protesters, but there are few calls for a military trial as speedy as the one Romania’s deposed dictator received.

“The Egyptian revolution is not to gloat over Mubarak, but to establish a new democratic system based on law,” said Essam al-Erian, a leading Muslim Brotherhood member, in a recent television interview. “He should only be tried before a military court in a military case.”

But in a demand that echoes the Ceausescu case, many politicians and protesters in Egypt are calling for a public trial for Mubarak, along with other key members of his fallen regime. During protests in Tahrir Square in April, protesters conducted mock trials for Mubarak, headed by real judges.

The biggest concern for many in Egypt, though, is the return of the money that Mubarak and his family allegedly stole from the state. On this charge, Egyptians can look to Taiwan as an example.

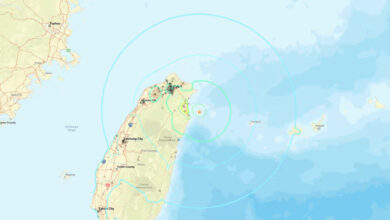

The Taiwanese did not depose president Chen Shui-bian in a popular uprising, which means his case is quite different from Mubarak’s. However, the state did successfully prosecute him for corruption.

The prosecution waited until one hour after Chen left office – and thus no longer enjoyed presidential immunity – before preventing him from leaving the country. Taiwan’s president from 2000 to 2008 went on hunger strike and claimed he was being persecuted for his anti-Beijing views by his successor, Ma Ying-jeou, who thawed relations with China.

Chen pleaded "not guilty" at the start of his corruption trial, but his son, daughter-in-law and brother-in-law all pleaded guilty to laundering large sums of money for the family.

On 11 September 2009, a Taiwanese court sentenced Chen, his wife and other relatives to life in prison after finding them guilty of corruption.The total sum of money involved in the case equaled roughly US$11 million.

Many figures from Egypt’s ousted regime, including the Mubarak family, face charges relating to corruption and profiteering. Former First Lady Suzanne Mubarak relinquished LE24 million of allegedly grafted money but was subsequently released. Yet the prosecution announced that she may still face other charges if new evidence appears.

As preparations for Mubarak’s trial continue, it is worth noting the stark contrast with Tunisia, Egypt’s North African neighbor and the first country to revolt in the so-called Arab Spring.

In Tunisia, a popular revolution overthrew Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali, who ruled the country for 24 years.

After weeks of protests calling for the fall of his regime, Ben Ali escaped on the night of 14 June in his private jet. He is now living in Saudi Arabia as a political refugee and has not faced trial, but his and his family's properties inside Tunisia have been frozen and some of his wife's relatives had been arrested. Tunisians continue to demand the freezing of their assets outside the country as well.

In the end, Egypt is unique and will not follow in the footsteps of any other country, either in Europe, Asia or North Africa.

To an extent, many Egyptians crave revenge. But moreover they crave justice. As Nasr Amin of the National Council for Human Rights recently said, “We want it a fair trial. Although being transferred to criminal court means that there is strong evidence against them, they still have the right to defend themselves.”