H5N1, also known as avian influenza or bird flu, has apparently found a perfect environment to thrive in Egypt. Since the initial onset of the virus back in 2006, new outbreaks of the flu have occurred every single year, making Egypt one of the world’s few endemic countries for the virus, along with Indonesia and Vietnam. The government, taking the threat of a pandemic seriously, has launched annual vaccination campaigns to mitigate the number of fatalities in Egypt, which made up 55 of the 159 total reported cases according to the World Health Organization.

The amount of data collected by Egyptian veterinary services and bird flu specialists on the ground since 2006 is massive, yet these scientists lack proper technology that could track the virus and identify areas where the virus could potentially strike again.

Three specialists from the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA) conducted a three-day workshop this week to familiarize Egypt’s leading researchers, vets and ecologists with Geographic Information System (GIS), a system designed to capture, manipulate, analyze, merge and present all kinds of geographically referenced data to track the bird flu virus across the country. GIS merges cartography, statistical analysis and database technology and has proven extremely useful in fighting epidemics and pandemics worldwide, giving precious help to epidemiologists who specialize in tracking viruses.

Ryan Harrigan is a postdoctoral student at UCLA who specializes in spatial modeling for avian influenza. After installing GIS software on the attendees’ laptops, he kept hopping around from one person to another to help them use the program.

“Everything we do,” he explains, “is linking cases of influenza with the environment that surrounds it. What makes a site have positive cases and another devoid of them? Farming practices, land use, density… in what type of environment does H5N1 persist in?” he asks, stressing how interesting Egypt’s case study is.

The training is financed by the US National Institute of Health and Fogarty International Center, the latter having a program that focuses on avian influenza across the world, with an emphasis on Africa.

Harrigan explains that “the reason why these health institutions have a particular interest in funding this training in Egypt is because there is a greater chance that a pandemic will develop in a country where the virus is already endemic, rather than in countries like Cameroon where an outbreak occurred once and then disappeared.”

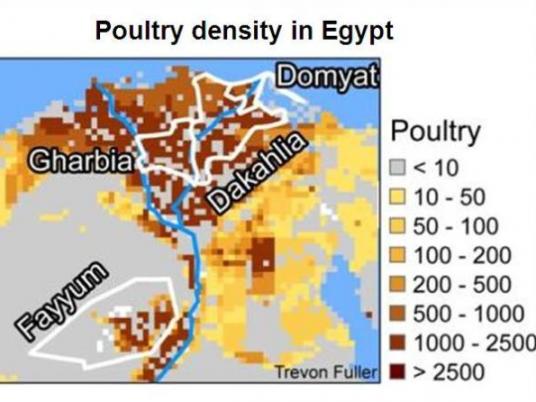

Kevin Njabo is a researcher at UCLA’s department of ecology and evolutionary biology and associate director of the university’s center for tropical diseases. His interest lies in ecology and the evolution of tropical diseases, biodiversity management and conservation. According to him, one of the many reasons explaining Egypt’s vulnerability to bird flu is “the millennial tradition of poultry breeding which dates back to Ancient Egypt.” The fact that most residents in rural areas breed chickens, ducks and geese in their houses’ backyards or rooftops creates an immediate proximity, which explains why most reported cases originate for the countryside. Another decisive factor is what he calls “the constant source of influx of the virus to the population that is increased by the commercial poultry farms selling parts of their production to open air markets.”

Trevon Fuller is the third UCLA researcher who conducted the training session. A postdoctoral researcher and expert on spatial modeling of infectious diseases, he hopes that a trialof this software will be successful, “because the amount of data collected since 2006 in Egypt on bird flu is gigantic, and having this data reflected by the GIS will give an accurate overview of how the virus spread.”

Not only this, he adds, but this modeling tool will also bring a vast array of factors together — like density, water presence and altitude of the location — and correlate them, which will help identify the most significant factors that trigger bird flu outbreaks. Njabo explains that identifying the environmental factors will help determine high-risk population centers before the epidemic reaches them because they have similar environmental characteristics as the infected areas. This would mitigate the impact of another potential outbreak.

“Awareness campaigns will have to be conducted in these potentially threatened areas, to teach people simple hygiene practices that are really efficient to prevent infection by the virus,” Njabo says.

But, Njabo feels that the main problem is poverty. Also, the blatant distrust that exists between the people and the state needs to change, so people report cases of dying birds without fearing that their source of income will be wiped out. Many farmers fear that identifying their poultry as infected will result in a government order to cull the birds without compensation.

“No one will speak when in fear of some kind of retaliation,” he says.

Harrigan also sees another aspect that needs improving to track the virus with more accuracy.

“There is a disconnect between the people collecting the data, the breeders and the modeling people, which does not contribute to giving a clear image of how the virus is developing on the ground,” he stresses.

What he is already certain of is that the entire Egyptian population being crammed onto 5 percent of the country’s land allows bird flu to spread at a fast pace.

Although the chance that the virus will mutate to become transmissible from human to human is very unlikely, Fuller insists on the importance of mastering all the data to be able to mitigate the consequences of this disastrous scenario.

Basma Sheta, one of the attendees of the training, is a PhD student from the University of Mansoura. She is an experienced field researcher who studies the transmission of the H5N1 virus from migratory birds to domestic birds. She conducted fieldwork at the beginning of the year in the Monufiya, the governorate which has been the most harshly hit by the virus so far, and she can already assert that the virus is becoming more aggressive.

“For the first time, I found a case in a wild but resident bird, which proves that the virus is in mutation,” she says.