Amro Selim is not the first Egyptian cartoonist, and he certainly does not want to be the last. In addition to his continuous creative outpouring, Selim has almost single-handedly paved the way for a new generation of cartoonists to blossom and rise to the forefront of the scene.

With the re-launch of Al-Dostour newspaper in 2005, Selim, along with the paper’s former editor-in-chief, Ibrahim Eissa, triggered a boom at a time when the state’s security apparatus tried to maintain its strong grip on all media outlets.

Here, Selim talks through the developments of cartooning in Egypt and the fine line cartoonists navigate between revolutionary positions, a controlling political regime and a culturally sensitive public.

Egypt Independent: How do you identify promising cartoonists when you first see their work?

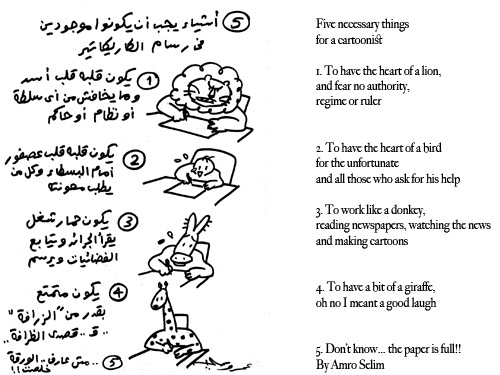

Amro Selim: Cartoons might seem like simple humorous illustrations. But pulling off a good one is no easy task. I judge a cartoon based on the strength of its concept, and how bright and witty it is, even if the illustration is not that great.

Drawing is a skill that can be developed through practice, wheras a cartoonist’s ideas might not.

A good cartoon is about the right mix: a bright idea, a lively illustration and a strong and informed political position. Think of the cartoonist as a filmmaker, who creates characters, sets and all the details to make a point and immerse viewers into the scene presented.

EI: You have often spoken of how impatient readers can be while viewing cartoons, unlike while looking at an artwork. How do you get readers immersed during the very brief encounter they have with a cartoon?

Selim: The illustration must be captivating, the lines lively, so readers do not flip the page. Readers need to feel the smoke coming out of the little chimney on the sweet potato cart in the cartoon.

What helped me a lot when I was starting off were issues of Rose al-Youssef magazine that my father brought home. The lines of Bahgat, Hegazi and al-Labbad fascinated me. They had their unique characters and sets that readers identified with.

So I often advise emerging cartoonists to familiarize themselves with the work of this older generation of Egyptian cartoonists. They are not readily available online, so people need to dig up old issues of Sabah al-Kheir magazine from 1956 until the mid-1970s to find them.

Then you develop your stock of tricks: different eyes, mouths, glasses, offices … for various characters and situations.

EI: But might not the stock of tricks make cartoonists fall in the trap of repetition, especially because political events are somewhat similar?

Selim: Well, cartoonists need to occasionally scrap their work and start anew. For a long time I was too proud of what I did and could not throw out any of my drawings. So I did not progress much. Once you have the heart to do that, things start rolling.

I also generally prefer to use a wooden pencil that is thick and less accurate. It allows for unintentional turns, new lines that might surprise me.

But the dynamic context in Egypt also helps us to constantly develop our work. Every morning, one wakes up to find an unfortunate incident to work on.

And recently, the changes have been more sweeping. We would have never imagined having a bearded president, for instance. But it happened, so we are adding beards to our stock.

EI: You are one of the few who care about grooming a new generation of cartoonists in Egypt. Why is that so important to you?

Selim: When I started working at Rose al-Youssef newspaper, only two people dominated the scene, and they tried to crush everyone else. Luckily, some cartoonists from the 1960s generation mentored me.

Over time, I felt more and more that there was a need for fresh faces and ideas. But it was not until Al-Dostour newspaper re-launched in 2005 that I got the opportunity to do something about it.

I was still working at Rose al-Youssef when I came across the work of Makhlouf and Abdallah. But there was little room for emerging cartoonists there, particularly because of the newspaper’s promotion of the political regime.

Al-Dostour, on the other hand, was a brave experiment. Editor-in-Chief Ibrahim Eissa [an outspoken opposition journalist] loved cartoons and wanted to establish a strong department. He invited me to head it. And I contacted Makhlouf and Abdallah immediately.

It was a very promising start. Then you came along Andeel, only 18 years old. You were the youngest cartoonist on board. Later, Doaa al-Adl joined, paving the way for women cartoonists in Egypt.

We also had Waleed Taher, Hany Shams and Anwar. Now, most of them head the cartooning departments at major newspapers, which is great.

If someone were to ask about my best work, I would not choose a cartoon, but the collaboration I started with early career cartoonists. Collaboration is what keeps our profession going.

EI: Do you feel that political changes between 2000–2005 helped new cartoonists to emerge in the journalistic field?

Selim: Al-Dostour emerged at a time when cartooning was dying in Egypt even at newspapers like Rose al-Youssef. Photography was taking its place. It simply felt safer for the editors working under the [Hosni] Mubarak regime. There was maybe a maximum of four cartoons published in a complete newspaper issue.

At Al-Dostour, I remember that we once counted 70 cartoons in a single issue. The following week, the editor in chief of Rose al-Youssef, where I also worked, asked me to create a cartooning department like Al-Dostour’s.

I believe that many times, Al-Dostour was selling because of the brave cartoons, and when we moved to Al-Masry Al-Youm, it was also selling because of them. Every new newspaper started considering which cartoonist it would hire, whereas before there was a time when they shunned cartoonists to avoid trouble [with the regime].

But I also differentiate between these developments and what happened in the two years of the revolution as the assaulting authorities have changed.

Before the revolution, cartoonists were either with or against Mubarak. Now there are so many new variables. You could be pro-Muslim Brotherhood or secular, a liberal or a leftist.

Having different political positions is good. I have my differences, for instance, with Tawfik, who is a great cartoonist. I like [longtime reform advocate] Mohamed ElBaradei, but Tawfik can send me a cartoon criticizing him and I publish it because it is a great illustration and the idea is done smartly. The things that should not be tolerated are racism or sectarianism.

Online committees are another recent development. When we criticized the National Democratic Party, there was rarely a public response. Now try to criticize President Mohamed Morsy, the Brotherhood, the Salafis or even draw a beard, and you come under severe attack because you are believed to be criticizing Islam.

They have become synonymous with Islam, and so has the beard and niqab. This is why it is so dangerous. Before you were against corruption; now you are fighting corruption under the guise of religion.

EI: So how can cartoonists navigate through this growing form of public censorship? We remember a few years ago Makhlouf drawing a cartoon of a young boy who stood with two women in niqab, telling them “Whoever is my mom, please give me LE1.” He was severely attacked, and it was the first time we heard the term “the atheist artist.”

Selim: We need to constantly push the boundaries whether they are set by society, the political regime or even a newspaper’s editors. If people equate your critique of a bearded political Islamist figure with atheism, then you must do it more, all the time, on purpose.

This is ground that we are gaining. It is a battle with possible lawsuits and threats. But we must continue.

We went through a lot to be able to draw the president every day. We won ground under Mubarak’s rule. At the beginning of Al-Dostour, I told them that we must shatter the god-like image of the ruler who we cannot draw.

We started drawing him from the back, and bit-by-bit we turned him around, until making a cartoon of him became the norm. Then we drew his sons, Gamal and Alaa.

We were very happy when these cartoons were published. Before that, if Mubarak were ever represented, it would be with Egypt holding him like her beloved son.

We have come a long way in a society that asked us to “respect” the ruler. Now, they want us to go back.

When you see people dying or losing their eyes and limbs, you find yourself addressing topics fiercely. When you hear about the virginity tests and find the authorities and public defending them, I feel we have to strike back with the same intensity, even if some will be offended. Society will not change unless you challenge it.

As for editorial policies, they can be navigated through a mixture of negotiations and subtlety. I believe there is a communication channel between cartoonists and readers that even editors might miss. It is amusing to experiment with overcoming censorship.

This piece was originally published in Egypt Independent's weekly print edition.