Among the photographs, videos and text pieces that make up the bulk of work in PhotoCairo 5 are six small pencil drawings hanging in a row. Each is a depiction of the same man’s face; and looking straight on, he gazes levelly at the viewer. His eyes, drawn in detail beneath equally elaborate eyebrows, are the constant, while the rest of his face, vaguer, shifts from drawing to drawing. He’s clearly undergoing a long-term program of facial surgery.

The label explains that this is artist Hanaa Safwat’s father, and that together she and he photographically documented his face during an illness.

Looking at the drawings, which are not in chronological order, you can’t reconstruct what happened, you can’t tell how much hope or tragedy there is in them. There is no specific mood.

Safwat was asked if she would like to add a picture of her father as he originally looked, or a self-portrait, but she thought better of it. “If there was a picture of him you would focus on the injury,” she says, and “there’s no denying that it’s a personal project, but adding a self-portrait would be pushing it too far.”

Once she delivered the drawings, she was offered a choice of frames and chose a simple black one. Apart from that, all she did was request that they not be hung in order — so “you can’t go forward and you can’t rewind” — then she didn’t see them again until the exhibition’s opening.

It is the first time that Safwat, 25, has exhibited her work. She studied set design for six years at Helwan University’s Faculty of Fine Arts, doing only college projects, which she reckons are the same projects that have been assigned in that department for 50 years. Everything she made there was forced, she says — with each project, the subject was dictated and numerous “research” sketches had to be produced. This taught her the value of spontaneity. Her work wasn’t well received, but she’s glad she didn't study painting, because, “I would have been turned off painting, instead of set design.”

She had one inspirational but elderly teacher, she said — Nagy Shakir, who is represented in PhotoCairo 5 by an experimental film he made in 1972, “Summer 70,” in a film program selected by Tamer El Said (which has been postponed to March 2013). Safwat thinks that he was able to see students’ work in a different way because he started at the faculty before the curricula became formulaic.

So as a painter, she’s self-taught. But she recently remembered being good at drawing as a child, having found a school report in which a teacher gave her an “O” for outstanding.

“I started remembering all the little drawings I made as a child,” she says. Born and raised in Cairo, she spent two years between the ages of 5 and 7 in Maryland, in the US, which seems to have been a golden age for her childhood art production. “I remember the first time I bragged about being able to draw,” she says, and that she proved it by drawing an older girl’s ear.

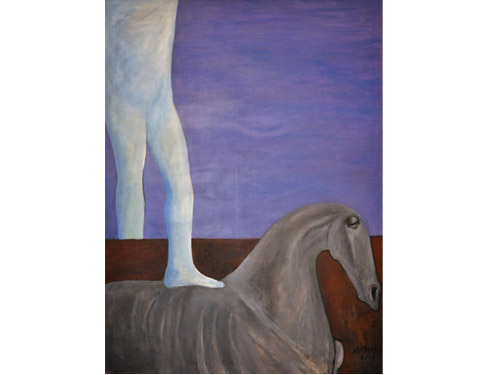

She started making her own work again during the final months of college, when she was meant to be working on her graduation project. She painted a self-portrait as an exercise, then felt ready to tackle the paintings of her father, beginning with the six sketches. Due to the revolution, which began in the middle of the series, it took her about a year to make them.

Early on, she approached Mia Jankowicz, director of the Contemporary Image Collective and curator of PhotoCairo 5, because she needed someone to look at the paintings objectively and give her feedback. “I really loved what she said,” Safwat says, explaining that Jankowicz pointed out things that she had thought about but not verbalized when making them. “It made me think, this painting thing really works!”

Some months later, Jankowicz asked to do a studio visit, and this led to the drawings being part of PhotoCairo.

For two reasons, Safwat was never interested in just exhibiting the photographs. “I didn’t want it to be a spectacle, because some of them are very graphic, and drawing or painting tones it down. Secondly, the photos were just documentation […] and I needed to take this and filter it through myself and make it a painting.”

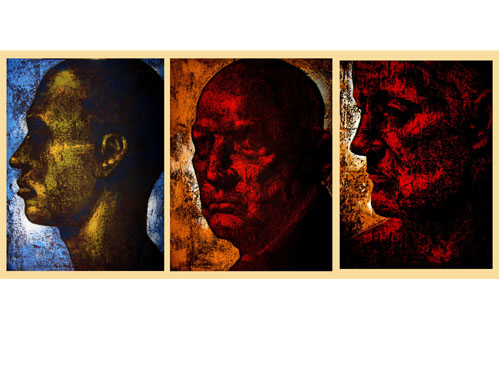

So far, one and a half paintings exist. They are as loud as the drawings are quiet, large and with bright patches of oil color on canvas. She says they are constrained by the limits of her technical ability, but that this is something she is interested in: “I wanted to leave it unlearned and the way it was.”

Recently she decided to take a break and work on a lighter, less sad project. She’s about to start photographing people’s tongues, getting them to replicate as adults the childhood gesture of sticking out one’s tongue at people. She’s still deciding exactly how she wants to present the results of the tongue project.

She has a fairly relaxed attitude toward her art career, having never been drawn to the idea of showing in the Youth Salon or in one of Cairo’s commercial galleries. “I might stop if I run out of ideas,” she says, but meanwhile works slowly and steadily on those that she has.

Concerned somehow with the revolutionary moment, PhotoCairo 5 explores shifts, transformations, the reshaping of reality. In Safwat’s six drawings, the revolution echoes on a small scale. The invasive surgery brings to mind, unlike anything else in the show, the repressive regime’s deliberately invasive impact on dissenters’ bodies, yet isn’t connected to that at all. The adjustments that the patient and his friends and family have to make during his illness, which one may wonder about when looking at the drawings, are not dissimilar to the whole damaged country itself having to adjust its outlook and its relationship with itself, come to terms with its vulnerability and yet continue to fight.

The pencil marks are alternately softly tentative and firmly confident, and overall they combine objectivity and tenderness. They are not exactly defiant, but nor do they ask for pity. They are drawn straightforwardly, and this simplicity and humanity makes them stand out in the show.