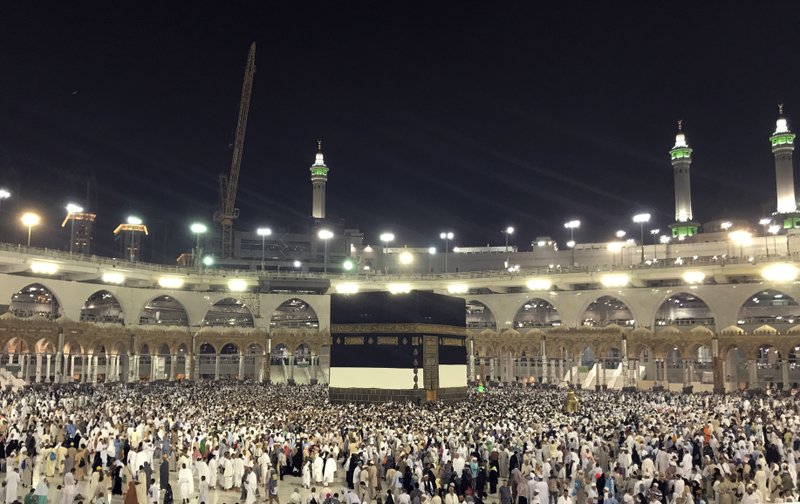

More than 1.7 million Muslims from around the world have arrived in Saudi Arabia for the start of the annual hajj pilgrimage this week. Once in Mecca, the site of Islam’s holiest place of worship, they will be reminded that the ruling Al Saud family is the only custodian of this place.

Large portraits of the king and the country’s founder hang in hotel lobbies across the city. A massive clock tower bearing the name of King Salman’s predecessor flashes fluorescent green lights at worshippers below. A large new wing of the Grand Mosque in Mecca is named after a former Saudi king, and one of the mosque’s entrances is named after another.

It’s just one of the many ways that Saudi Arabia uses its oversight of the hajj to bolster its standing in the Muslim world, and to spite its foes, from Iran and Syria to Qatar. Its archrival, the Shiite power Iran, has in turn tried to utilize the hajj to undermine the kingdom.

The hajj has long been a part of Saudi Arabia’s politics.

For nearly 100 years, the ruling Al Saud family has decided who gets in and out of Mecca, setting quotas for pilgrims from various countries, facilitating visas through Saudi embassies abroad and providing accommodation for hundreds of thousands of people in and around Mecca.

The kingdom has received credit for its management of the massive crowds that descend upon Mecca each year, and blame when things go wrong at the hajj. All able-bodied Muslims are required to perform the pilgrimage once in a lifetime.

Saudi kings, and the Ottoman rulers of the Hijaz region before them, all adopted the honorary title of Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques, a reference to sites in Mecca and Medina.

“Whoever controls Mecca and Medina has tremendous soft power,” said Ali Shibahi, executive director of the Arabia Foundation, a pro-Saudi center in Washington. “Saudi Arabia has been extremely careful from day one not to restrict any Muslim’s access to hajj so they never get accused of using hajj for political purposes.”

The Syrian government, however, says Saudi authorities continue to place restrictions on Syrian citizens looking to take part in the hajj. Saudi Arabia has no diplomatic ties with President Bashar Assad’s government and since 2012, requires all Syrians seeking to make the hajj to obtain visas in third countries through the “Syrian High Hajj Committee,” which is controlled by the Syrian National Coalition, an opposition political group.

The hajj became further entangled in politics following the fallout between Saudi Arabia and Qatar when the kingdom and three other Arab countries cut all diplomatic and transport links with the small Gulf state this year. In a surprise this month, Saudi Arabia announced it would open its border for Qatari pilgrims seeking to perform the hajj and that King Salman would provide flights and accommodation to Qataris during the hajj.

The Saudis, however, announced the goodwill measures unilaterally and did so after meeting with Sheikh Abdullah Al Thani, a Qatari royal family member who resides outside Qatar and whose branch of the family was ousted in a coup more than four decades ago.

“Bringing out a senior member of the Qatari royal family member was a political coup really,” Shihabi said.

Others have gone further, saying that by promoting Sheikh Abdullah, the Saudis were attempting to delegitimize Qatar’s current emir.

Gerd Nonneman, a professor of International Relations and Gulf Studies at Georgetown University in Qatar, says the Saudi move was “a transparent propaganda stunt”.

“Given that Qatar’s hajj attendance has inevitably been affected by the boycott, the hajj was de facto politicized — there’s no way around it,” he said.

Qatar’s government publicly welcomed the move to facilitate the pilgrimage, but also called on Saudi Arabia to “stay away from exploiting (the hajj) as a tool for political manipulation”.

Qatar’s human rights committee had previously filed a complaint with the U.N. special rapporteur on freedom of belief and religion over restrictions placed on its nationals who wanted to attend the hajj this year. Saudi Arabia’s Foreign Minister Adel al-Jubeir said Qatar’s complaint amounted to a “declaration of war” against the kingdom’s management of the holy sites, and the kingdom accused Qatar of trying to politicize the hajj.

While the hajj is a main pillar of Islam, the custodianship of its holy sites is a pillar of the Al Saud family’s legitimacy and power. Iran has consistently tried to call that into question.

Two years ago, a stampede and crush of pilgrims killed at least 2,426 people, according to an Associated Press count. Iran, which lost 464 pilgrims in the stampede, immediately used the disaster to call for an independent body to take over administering the hajj. Those calls were vehemently rejected by Saudi Arabia, which accused Iran of politicizing the hajj.

The hajj took place last year under the shadow of the two countries’ rivalry. Saudi Arabia and Iran severed ties in 2016, and as a result, no Iranians were at the pilgrimage last year.

It wasn’t the first time Iran and Saudi Arabia sparred over the hajj. In 1987, Saudi police opened fire on Iranian pilgrims protesting during the hajj, killing more than 400 people. For two years after that, Iran did not send pilgrims to the hajj.

Ahead of this year’s hajj, Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei essentially called on pilgrims to hold protests again, saying the pilgrimage offers “Muslims with a great opportunity to express their beliefs”.

“Where else, better than Mecca, Medina … can Muslims go to express their concerns regarding Al-Aqsa and Palestine?” Khamenei said, referring to one of Islam’s holiest and most contentious sites in Jerusalem.

Senior Saudi clerics were quick to respond, saying the pilgrimage should not be exploited and reminding worshippers that the ultimate goal of the hajj is “to spend all their time and effort in worshipping Almighty Allah.”