Love is a subject that has animated great poetry, novels and memoirs for a thousand years and more. Hate has been explored comparatively little.

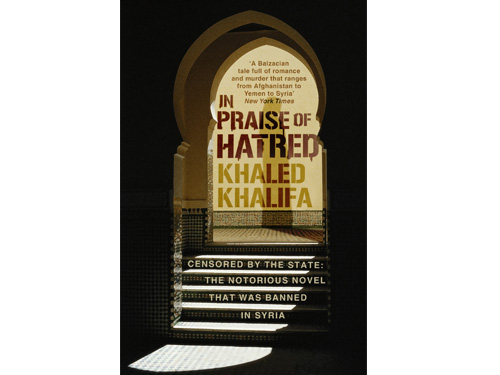

Khaled al-Khalifa’s “In Praise of Hatred,” shortlisted for the 2009 International Prize for Arabic Fiction and available in English translation in 2012, is powerfully seductive in its exploration of hate. The novel is deceptively straightforward: it is a chronological story told by a young woman who is part of a large Sunni family. Most of the action takes place in the early 1980s, when Islamist Sunnis led an uprising against the primarily Alawi Syrian regime.

The echoes with the current Syrian uprising are many. Translator Leri Price notes in her afterword that she was working on a passage about arrests and interrogations at Aleppo University when she turned on the news to hear of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s purge at the same university.

But the two situations are also, as the author has noted, very different: the current uprising belongs to a much wider swath of people. What remains the same is the nature of human hate.

The novel, which received a warm and fluid translation from Price, focuses primarily on the lives of Aleppan women. The book in some ways represents the coming of age of its nameless adolescent narrator. She is a bright young woman raised in her conservative grandfather’s home, and her uncles and older brother are leaders in the Islamist uprising. She is as clever as any of them, but restrained by her home, her clothes and her ideas; later, she is restrained by the violence all around her, and finally by prison.

The novel crams a large number of characters into each of its narrow spaces, and creates a powerful density that brings late-1970s and 1980s Aleppo to life. The narrative has a number of male characters, but focuses mainly on the lives of women.

In school, the narrator finds a sharp distinction between girls who align themselves with the mukhabarat, or intelligence services, and those who align themselves with the power of an austere Islam. The girls here have limited choices, but they are never mere pawns. Instead, they are agents in a complex landscape.

In navigating this territory, the narrator finds that hate gives her the ability to rise above it all. The narrator is charmed by her beautiful schoolmate Ghada, who is having an affair with a senior mukhabarat officer, but chooses to join the severe Alya.

“By the end of that summer,” she says, “hatred had taken possession of me. I was enthused by it; I felt that it was saving me. Hatred gave me the feeling of superiority I was looking for.”

Although she continues to desire Ghada’s companionship, the narrator can never really have her. But through hatred, she can have power.

“We need hatred to give our lives meaning,” the narrator thinks as she celebrates her 17th birthday alone. Hatred is what the narrator does to define herself, to sublimate her loneliness, and to lift herself above others.

Hatred becomes even more necessary when Aleppo is under siege, caught between two sects: the one leading an uprising and the other violently crushing it. Under the strain of constant anxiety, the family begins to break apart.

The narrator’s mother cannot bear her eldest son’s imprisonment, and is barely available. Maryam is the most severe of the aunts, and her life is largely dry and empty. Safaa has a turbulent life, married to a mujahid who allies himself with the CIA in the Afghani-Soviet war.

Only one aunt, Marwa, allows herself to fall unexpectedly in love.

Unfortunately for Marwa, she comes in contact only with the soldiers who search the family home, and she falls for an Alawi officer. When she attempts to meet her officer, her brothers order her chained to her bed.

The officer finally comes to liberate Marwa, and the two of them — the only two who attempt to reject hate — must in the end flee the city, into the countryside.

None of the characters are static. They often forgive one another and come tentatively back together. But the power of hate is seductive.

Maryam, after visiting Marwa, at first “sounded indulgent.” However, “in subsequent days all her anger came out: she spoke disparagingly of Marwa’s removal of her veil; and of my father’s alcoholism, and the fact that he cursed my mother and Bakr and our group, and praised the other sect.”

Hatred also offers a way to manage grief. When the narrator’s brother is killed during a brutal purge of one of the prisons, she “wanted to hug my mother and cry in her arms like a little child, but hatred dominated me to my very core. My extremities went cold. I felt paralyzed and indifferent. I didn’t care if I ever emerged from the dark tunnel I had entered.”

It is imprisonment, oddly, that unravels the narrator’s hate. After several years of being tortured in political prison, she finds herself thrown into a general women’s prison with Marxists, prostitutes and others. Here, she comes to love others from very different backgrounds and, “the hatred which I defended as the only truth was shattered entirely.”

The book’s English-language ending, which is revised from the original, is somewhat abrupt. But the rest of the book is richly rewarding, thickly layered and full of fresh understanding about human motivation.

The book’s density is sometimes overwhelming and stifling, but it echoes the sense of being trapped between hatreds. And while the book is very particularly about 1980s Syria, and fearlessly examines some of the nation’s most sensitive historical moments, it also transcends time and place. Just as a great love story can speak to anyone’s love, this can speak to anyone’s hate.

This piece was originally published in Egypt Independent's weekly print edition.