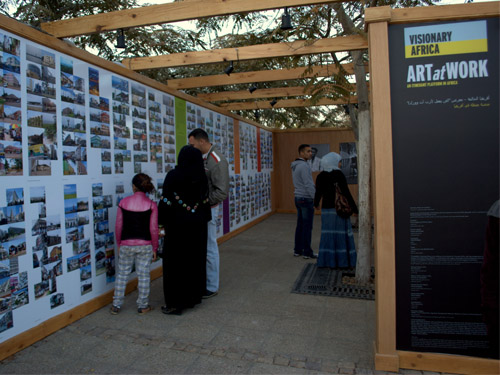

The exhibition “Visionary Africa: Art at Work” currently on display near the entrance to Al-Azhar Park is a project of high ambition, touring African capitals with the mission of bringing the cultural history of Africa straight to the people.

Plans for the project came in the wake of the Visionary Africa festival held in Brussels in 2010, coordinated by BOZAR, the Center of Fine Arts in Brussels, and now being carried out with the support of the European Commission. It is an endeavor of vast geography and multi-faceted partnerships, and for the next week, it will make its home in Cairo.

“Visionary Africa: Art at Work” began its journey in Tripoli a year ago, before making stops in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso; Addis Ababa, Ethiopia and now Cairo. After the exhibition in Cairo closes on 7 March, it will likely move on to Uganda and Cameroon, though plans are not yet firmly in place.

The main section of the exhibition, “A Useful Dream,” is a collection of African photography from the past 50 years curated by Simon Njami, a leading curator of contemporary African art, who has been involved in the Bamako Photography Biennale, as well as Africa Remix, a large exhibition of African art and photography that toured the world from 2004 to 2007, and a number of other high-profile projects.

The entire exhibition, which also includes a selection of work from Egyptian artists curated by Moataz Nasr of Darb 1718, a wall of images of the architecture of African capitals called “Urban Africa,” and a timeline of events in African cultural policymaking from the past 60 years, is housed in a temporary structure designed by David Adjaye, a world-renowned architect who is currently in the process of designing the National Museum of African American History and Culture, to be a part of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC.

Despite the big names and big plans, bearing the weight of a cultural diplomacy mission to better educate Africa about Africa, the exhibition itself is fairly modest. Adjaye’s pavilion is small but well-suited to its purpose; Njami’s selection of photographs provides an intimate if diffuse look at evolving culture and identity on the African continent. Nasr’s selection of work from local artists emphasizes, unsurprisingly, artistic responses to the 25 January revolution, with some works much better suited to the outdoor setting than others.

The pavilion is open and the works are outside in the air, a part of public space, allowing only for the display of photo-reproductions, not originals. Presentation of work is limited to printouts pasted onto the walls. “A Useful Dream” consists only of photographs, which suffer little in such a presentation. Kathleen Louw, project manager at BOZAR in Brussels, the coordinating institution behind the project, points out that this was intentional.

“Njami did not choose to include photographs of objects. … All the detail would be lost, so he just chose photography,” Louw says.

Nasr would have done well to follow Njami’s example. The work of Mohammed Monaiseer, consisting of delicate, dissolving fabric and calligraphy, is presented in printed photographs that maintain little of the detail of the original work. More carefully selecting work that can maintain its integrity in the limiting outdoor format would have greatly improved the Egyptian section of the exhibition.

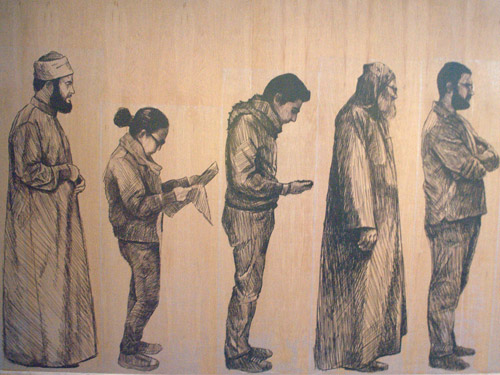

One important exception, however, is a digital reproduction of Mina Naser’s life-size drawings of Egyptians of every stripe standing in line to vote. The careful characterization of future voters, old and young, from activist to Salafi to buttoned-up banker, occupying themselves as they wait in an endless line for their first opportunity to participate in the semblance of democratic process, captures the hope and frustration of the present moment in Egypt. But more than that, the work also makes use of the public space, rather than simply existing in it.

For Njami, when planning the core section of the exhibition, convenience was not the only reason to focus on photography. The exhibition was timed in rough coordination with the anniversaries of independence of some 20 African nations from centuries of European colonization. These places, like Egypt, have long served as the subjects for visiting photographers’ searching lenses, for years represented in the West primarily through the eyes of Westerners.

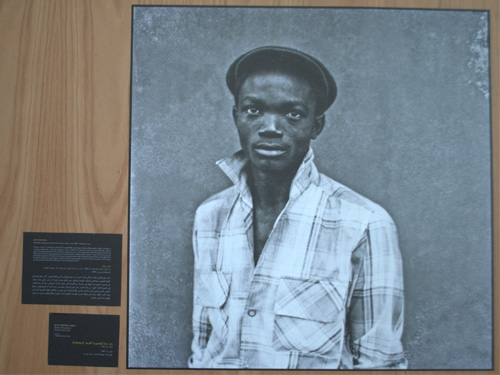

“Njami chose photography not only for its documentary quality, but also for its potential to reverse the Western gaze on Africa. … It is a reclaiming of photography that he wanted to emphasize,” says Louw.

Many of Njami’s images depict urban Africa, full of fashionable youth and cosmopolitan nightlife. Images of the 1960s to 1980s in particular show stylish, energetic youth dancing, posing and engaging with a lively pop culture. In Congolese photographer John DePara’s “Franco a la Casquette” a young man, a popular singer, stares into the camera with a look of hipster disaffection and vague melancholy. Philippe Koudjina, a photographer renowned for his images of sweaty nightclubs, was such an effective man-about-town that he managed to catch renowned Italian documentarian Paolo Pasolini and the glamorous opera singer Maria Callas by surprise as they crossed the tarmac at the airport, visiting newly independent Niger. Samuel Fosso’s self-portrait shows the artist in sunglasses and bell-bottoms, posed in the classic image of 1970s fashion and attitude.

Njami structures the exhibition chronologically, and it becomes a rough education on the recent history of the African continent, including images such as Mohammed Amin’s photograph of infamous Ugandan Dictator Idi Amin Dada being sworn in. Njami is quoted in the press material for “Art at Work” stating, “What we plan to show within this structure … are moments,” and some of those moments are dark. As Njami writes in his curatorial commentary, “Dreams turn to nightmares and illusions borne out of independence give way to a social and political mess.”

The images and individual photographers carry with them a wide range of cultural and historical associations that are explicated to some degree by the detailed texts. But their collective impression is of isolated moments within the history of a vast and diverse continent, leaving many more questions than answers. This fulfills Njami’s curatorial vision of capturing moments and also underlines the difficulty of talking about all of Africa, all at once.

“Visionary Africa: Art at Work” extends beyond the exhibition. It is set up to engage in a high level of collaboration with local institutions and artists. A workshop, an artist residency and the inclusions of the exhibition of local artists are all a part of this strategy. It is difficult, however, to accomplish so much in the scope of one project. High-profile visitors like Njami were not able to spend extended time in the city, and weak institutional support made it difficult for South African resident artist Tracey Rose to engage extensively with the local arts community.

“It was overall not easy for her,” says Louw of Rose’s experience.

But one thing is clear: Al-Azhar Park is an excellent location for an art exhibition. The park brings a large, curious audience of young people in the mood to relax and wander about, and, according to Louw, 6,000 visitors have been passing through the exhibition every day since its opening — a larger audience than most exhibitions in Cairo could ever hope to attract.