Immediately following the first 18 days of the revolution, Egyptian women around the country had greater hopes that their profile would be raised in the spirit of equality that had defined the protest movement. Women’s role in the revolution had been highlighted, and harassment had almost disappeared from Tahrir Square.

The celebrations were, however, short-lived. In early March 2011, a demonstration to celebrate International Women’s Day in Cairo was attacked, with some women sexually harassed, and dragged out of the crowd.

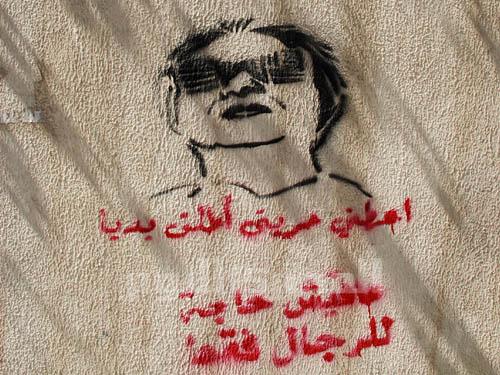

One year later, a group of young women and men, NooNeswa, launched a campaign that seeks to change attitudes toward women in Egypt. Their first project, “Graffiti Harimi” (“Female Graffiti”), aims at breaking social taboos through graffiti.

The idea is for women to reclaim public space, according to Nawara Belal, a member of NooNeswa.

“Women are not comfortable in public places,” she told Egypt Independent. “We must feel that we belong there, that it’s our zone.”

On 9 March, the group started by stenciling images of powerful Egyptian women with thought-provoking quotes around the Maadi neighborhood, right under the eye of the Egyptian police.

The designs by artists Elmoshir and Diaa Elsayed portray mostly Egyptian singers and actresses in a style akin to Paris’ Miss Tic. While the Montmartre fame is individualistic and tongue-in-cheek, NooNeswa’s messages remain positive and straightforward in their criticism of attitudes toward women.

In one design, actress and singer Shadia is shown uttering “I opened the sluice,” referring to one of her most memorable scenes in “A Touch of Fear,” a movie in which Shadia’s character saves a village from the hands of a despot leader. “A Touch of Fear” is said to have been criticizing the policies of former Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser.

“This is a very powerful, feminist figure,” said Merna Thomas, NooNeswa’s leader.

There’s also a graffiti of the legendary Oum Kalthoum, singing a line from her famous take on “The Ruins” by poet Ibrahim Nagi, “Give me my freedom, set loose my chains.”

In another design, Egyptian sweetheart Soad Hosny proclaims that “Girls are like boys,” a quote from one her anthems that shows that everyone is created equal.

The irony that most slogans and heroines date back 50 years does not escape Thomas.

“It’s sad that we have to go back to the 1960s, when the feminist movement [in Egypt] was doing better,” she said.

Thomas said she deplores the current portrayal of women in the media as weak or inferior to men. According to her, there hasn’t been a strong public female figure in a very long time in Egypt, and that’s one reason behind the project.

“We’re trying to re-inject positive ideas and images to the public,” she said.

One exception to the lack of strong women in recent history could be Widad al-Demerdash, Mahalla’s famous protest leader. In one of the graffiti works, she declares, “Egypt gave birth to women,” a deliberate typo by NooNeswa on her well-known quote, “Egypt gave birth to men.”

Graffiti has emerged as a very intoxicating form of art on the streets of Cairo in the past year. Especially downtown, walls have been turned into bulletin boards, with many political notes addressed to the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces.

There’s also the wall protecting the American University from Mohamed Mahmoud Street. Since the Port Said football protests, it has taken the shape of a flourishing fresco to the memory of those who fell. Every day, Egyptians and tourists alike come to pose with the multitude of winged portraits.

“Graffiti is so powerful. There can be so many interpretations. It’s a great way to start a dialogue,” Thomas said.

And dialogue is badly needed, according to Thomas.

“You walk around and the only message you hear is ‘Go home!’ or ‘You’re not welcome,’” she said.

Also, women’s enormous loss of political power is of great concern to her.

“Let’s be honest. Things for women might not change soon enough,” she said.