Portrait photography has long been concerned with celebrity. Early photographs aimed to capture the stature of their subjects who were limited to a privileged class, as photography was an expensive medium. In Egypt, the first use of photography was for a portrait of Egyptian viceroy Mohammed Ali Pasha in 1839, followed by photographs of the royal family. As the medium grew more accessible it remained focused on fame. Published photographs were of royalty of a different sort: boxing champion Ezzidine Hamdi, diva Om Kalthoum, and writer Albert Cossery.

Almost a century later, portrait photography in Egypt is no longer limited to the wealthy, yet some associations with prestige persist. “Local Star,” a solo exhibition by photographer Ahmed Kamel, currently showing at Mashrabia gallery, examines the historical links between photography and celebrity, as well as the increasing fetishization of self-image in mass culture. The aesthetics–poses, costumes, backgrounds–evoke the work from commercial photography studios in Cairo, a common visual which belies Kamel's complicated message.

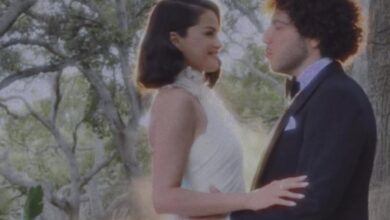

Since receiving his bachelor in fine arts in painting from the Faculty of Fine Arts in Cairo in 2003, Kamel has been exploring visual forms of self-representation, focusing on the personal, “idealized identity." “Images from the Parlor” defined families through their home interiors, "home being among the few spaces where people might express themselves freely, especially in big cities," Kamel explains to Al-Masry Al-Youm. His investigation of social identities continued with the series “Dreamy Day.” In this work, Kamel examined the pomp of Cairene wedding parties by photographing the bride and groom as they posed for wedding photographers.

“Local Star,” is a selection of twenty portraits of aspiring actors. In 2009, Kamel rented a studio in downtown Cairo, an area famous for its large community of performing artists. He advertised an open call for subjects, specifying only that they should arrive to the studio dressed “in their most splendid attire.” Over seventy people came, some with several outfits. Once there, they filled out a questionnaire, highlighting their favorite local and foreign stars, movie genres and dream roles, as well as their preferred colors. The studio was set up like a rehearsal space, encouraging the participants to perform, but the details of each photo were unknown to the subject. Kamel shot the photographs against a plain gray background, only later would he digitally construct backgrounds based on information he had gathered from the subjects. By doing this, he aimed to create what he considered to be a dream poster for each actor.

"The photographs are meant to be movie posters rather than portraits," Kamel tells Al-Masry Al-Youm. “They draw an analogy to the affectation common in the acting industry and hence are meant to emphasize the notion of a constructed image, of which the actor is an element." At first glance, the theatricality of the posters is their most obvious feature. The artifice in the body language and fake backgrounds are highlighted rather than disguised.

One subject, nine-year-old Mariam, idealizes Egyptian cinematic icon Souad Hosni and contemporary actress May Ezz Eddin, according to her questionnaire. Mariam poses suggestively, dressed in a halter top and skirt, looking at the camera with an unsettling, confident smile. Kamel has emphasized the disturbing mood by creating a gloomy violet seascape as a background for Mariam's image. Older female participants–aware of possible social stigma resulting from explicit representation of femininity in Egypt–are more subtle, feminine but playful.

Another subject, Mohamed Abdel Hamid, an actor in his twenties, impersonates a cowboy, both fierce and, through his facial expressions, humorous. Abdel Hamid's poster might normally be seen as cliche, particularly considering the mountainous desert background, but the portrait–or poster–is effectively satirical, commenting on the genre it both emulates and satirizes.

Where posters fail to strike a satirical balance, they can seem to ridicule the participating actors, despite Kamel's intention to create posters the actors can be proud of.

The photographs reflect both the aspirations of the subjects and Kamel's interpretation of those dreams through his choice of backgrounds and composition. In the course of preparing the show, he reworked the backgrounds multiple times to match the characters. His interpretation is based on cinematic roles and celebrities informed by years of close study of art and mass media. The most successful photographs link the subject to their persona while still presenting the actors as real people.

Other factors contribute, perhaps unintentionally, to the alienating effect of the photographs. Most of the subjects never saw the final posters and so could not comment on the chosen background or composition. It's unclear, too, to what degree the participants were familiar with the context of the exhibition; knowing that an element of mockery might be read into the final product, how many of them would have posed?

Is an eagerness to promote self-images potentially embarrassing or destructive, and at a time when this is widely available–made more so by social media–how much control does anyone have over how they are viewed? How is this obsession redefining celebrity in Egypt? These questions mean Kamel's photography is about much more than just the popular aesthetic he imitates, although the answers remain largely unclear.

Local Star is exhibited at Mashrabia Gallery of Contemporary Art from 19 September, 2010 until 14 October, 2010

8 Champollion Street, Downtown, Cairo

The gallery is open daily from 11 AM to 8 PM except on Fridays