Abu Dhabi, UAE (CNN) – Wednesday marks six months since the Kremlin launched its invasion of Ukraine. As Russia bombs its neighbor, what has become the biggest European war since 1945 has had an outsized impact far south, in the Middle East.

A volatile region with an array of existing problems, the Middle East was no exception to the disruptions brought on by the conflict in Europe — with food shortages and inflation causing fear of political unrest amid a tug-of-war for allies between Russia and the West.

But in other ways, some of the region’s countries have prospered immensely as the fighting rages on, adding hundreds of billions of dollars to their coffers.

Here are four ways the Ukraine war has affected the Middle East over the last six months:

Energy exporters are cashing in

The war has seen oil prices rise to as much as a 14-year high. That has resulted in soaring inflation and economic contraction globally, but for energy-rich Persian Gulf states, it’s good news coming after an eight-year economic slump caused by low oil prices and the Covid-19 pandemic.

The International Monetary Fund predicts that the Middle East’s oil exporting states will make an additional $1.3 trillion in oil revenue in the next four years, it told the Financial Times last week.

The extra money means Gulf states will have budget surpluses for the first time since 2014. Economic growth is also expected to significantly accelerate. In the first four months of this year, for example, the Saudi economy grew 9.9%, the highest in a decade. In stark contrast, the US economy shrank 1.5%.

The war has also brought opportunities for the region’s gas producers. For decades, European countries opted to import gas from Russia via pipelines instead of having it shipped from faraway nations by sea. But as Europe weans itself off Russian gas, it’s looking for potential new partners to buy from. Qatar has pledged half of its total gas capacity to Europe in four years’ time.

The EU has also signed gas deals with Egypt and Israel, both aspiring natural gas hubs in the region. And on a visit to Paris this month, UAE President Sheikh Mohammed bin Zayed al-Nahyan signed an agreement guaranteeing the UAE’s export of diesel to France.

Strongmen feel emboldened

Regional strongmen that once came under harsh criticism from the West appear to be back in favor.

Despite vowing to turn Saudi Arabia into a pariah, US President Joe Biden visited Saudi Arabia in a landmark trip last month. The move was seen as a capitulation to the kingdom’s weight in the global economy in the hope that it would produce more oil and tame global inflation ahead of the US midterm elections in November. That move largely failed, with the Saudi-led OPEC+ oil cartel opting for a modest rise in oil production, which one analyst described as a “slap in the face” for Biden.

The war has also allowed Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan to position himself as an indispensable figure in the international order. Faced with a sinking economy at home and elections next year, he has skillfully used his country’s geopolitical position to extract concessions for Turkey abroad by delaying the accession of Nordic countries to NATO. Erdogan has also maintained cordial relations with Russia while publicly opposing the war, selling coveted drones to Ukraine and even mediating between the belligerents.

Alliances are shifting

As trade routes shift with the war, so do alliances.

The UAE president’s adviser Anwar Gargash said in April that the war has proved that the international order is no longer unipolar with the United States at its helm and questioned the continued supremacy of the US dollar in the global economy. Abu Dhabi, he said, is reassessing its alliances. “Western hegemony on the global order is in its final days,” he added. The nation’s ambassador to the US said earlier this year that its relationship with Washington was going through a “stress test” after the UAE joined India and China in abstaining from a US-backed UN Security Council resolution condemning Russia’s war in February.

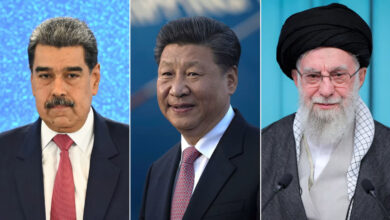

As relations with the West are reassessed, ties with China appear to be growing. The UAE last month referred to House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan as “provocative,” stressing its support for the one-China policy. Saudi Arabia has also touted China as an alternative to the US, stepping up military cooperation with Beijing and considering selling oil to it in yuan. Chinese President Xi Jinping, who hasn’t made any foreign trips since Covid-19 restrictions came into place, is expected to make a landmark trip to the kingdom this year.

“Where is the potential in the world today?” Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman (MBS) told The Atlantic magazine in an article published in March. “It’s in Saudi Arabia. And if you want to miss it, I believe other people in the East are going to be super happy.”

The US is taking note. In a Washington Post op-ed justifying his trip to Saudi Arabia, President Biden said he was putting the US in the “best possible position to outcompete China.”

Food and inflation crises raise tensions

Much of the world felt the impact of grain shipment disruptions following the invasion of Ukraine, but the Middle East was among the hardest hit.

Around a third of the world’s wheat comes from Russia and Ukraine, and some Middle Eastern states have come to rely on those two countries for more than half of their imports. War-torn Libya and economically shattered Lebanon took a hard blow from disruptions to the export of grain, along with Egypt — one of the world’s top wheat importers.

Ukraine’s grain exports resumed in late July following a UN-brokered deal between Kyiv and Moscow, and global food prices have stabilized since, but many in the Middle East are still waiting for stalled shipments.

The first ship carrying grain left Ukraine on August 1 and was initially bound for Lebanon. The shipment however changed course after Lebanese buyers refused the delivery, so it sailed to Egypt instead, according to Reuters.

Soaring inflation has also battered a number of precarious Middle Eastern economies. Rising commodity prices in Iraq and Iran have driven many to the streets in protest. And in Egypt, where just a decade ago an uprising toppled the former regime under the slogan “bread, freedom and social justice,” households of all income levels are seeing their spending power erode fast.