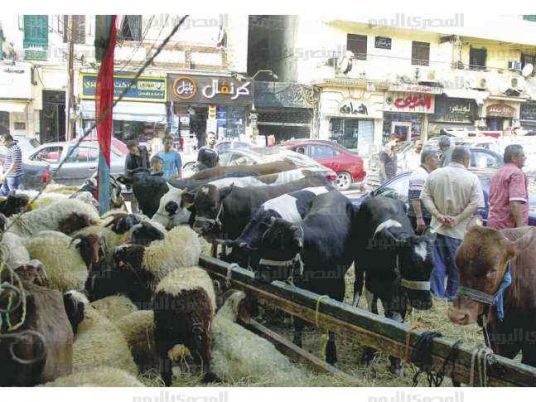

“Infectious diseases don’t care about politics or elections,” says Ahmed Abdel Hady, a farmer from Tabluha in the Nile Delta governorate of Monufiya. Abdel Hady is referring to the outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease that started in Egypt five months ago, an almost forgotten but still very pressing crisis that has been overshadowed by Egypt’s electoral hysteria.

Since its detection, the disease has infected between 70,000 and 100,000 cattle, killing more than 10,000 of them. The inability to ascertain the exact number infected says it all: the management the outbreak has been, to put it mildly, far from exemplary. Worse, the vaccination program currently underway to protect the rest of Egypt’s 6 million cows and water buffalo is already riddled with delay and controversy.

Foot-and-mouth disease is notorious for the high fevers it induces in cloven-hoofed animals, forming blisters inside the mouth and hooves. Highly infectious, it is transmitted by the saliva of sick animals but can live outside a host for long periods, spreading easily through contaminated clothes, hay and even the hands of livestock inspectors. However, eating infected meat rarely affects humans, as stomach acid normally destroys the virus behind the disease, known as a picornavirus.

Due to the novelty of this particular strain, SAT2, livestock in the region have not acquired resistance to it. SAT2 is normally limited to sub-Saharan Africa and has not been reported in Egypt for at least 50 years. A specific vaccine to match it has had to be mass produced from scratch. But since identifying the requirements for the vaccine, Egypt’s Veterinary Serum and Vaccines Research Institute, which the government tasked with producing the vaccine, has only made 300,000 units. These were dispersed to various governorates starting 19 April and have since run out.

The number is too small to curb the disease’s spread. Abdel Hady, the Monufiya farmer, has managed to vaccinate much of his livestock, though not without hounding government officials. Many of his neighboring farmers have not been so lucky, he says.

Just how lucky he is, however, remains unclear. According to Markos Tibbo, the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization’s (FAO) Near East Animal Protection and Health Officer, several emergency shortcuts have been taken in the production and testing of the vaccine, potentially rendering it ineffective, if not dangerous.

In assessing the acceptability of a vaccine, the organization requires documentation to validate the claim that production followed protocol and that vaccine batches passed quality control testing.

The requirements for such assurances are set up by the World Organization for Animal Health following international agreed upon standards. One of those standards is sending the vaccine to be tested for quality control — such as sterility, safety and potency — at a designated independent reference laboratory such as the World Reference Laboratory at the UK’s Institute for Animal Health. Instead, the vaccine was released after being tested for sterility and safety locally without undergoing remaining tests.

As such, the FAO has not been able to approve the vaccine.

“It may be perfectly good,” says Tibbo, “but we just need to make sure of that through scientific and supporting data.”

While the FAO has not approved the vaccine, it has helped train government staff in data collection, which will be crucial in determining the vaccine’s efficacy as well as ensuring its correct use. There is concern that, in a climate of intensified mismanagement, the possibility of immunizing already infected cattle is high. This can exacerbate the clinical symptoms of the disease, increasing mortality rates. More seriously, if the vaccine turns out to be ineffective, it may seriously compromise farmers’ trust in the government and further complicate the future possibility of controlling the spread of the virus.

Currently, it remains too early to tell if the vaccine is effective. The number of infected cattle was significantly dropping even before the vaccine was ready, a natural drop in the cycle of an outbreak. But without proper immunization on a mass scale, there is a real risk that the spread of the disease will pick up again in the coming winter.

“We will stop this from happening,” says Sayed Zeidan, deputy director for production at the Veterinary Serum and Vaccines Research Institute. Zeidan blames the delay in the vaccine’s production on complications in the import of newborn calf serum, a central component in the vaccine.

“This issue has now been resolved,” Zeidan says. On top of the 300,000 units previously produced, the institute has manufactured a further 400,000 units this week. “We intend to have made a total of 2.2 million units by the end of June — as stipulated in our contract.”

According to Zeidan, the institute complied with international protocols set up by the World Organization for Animal Health.

“But you have to remember this was an emergency situation. We followed the minimum requirements to at least be certain it would be safe and effective,” Zeidan says.

Just how safe and effective it is remains to be seen. In the meantime, serious concern over the spread of the disease to neighboring countries remains a priority for the FAO. The same strain of the virus was found in the Gaza Strip in April, which almost certainly spread there via cattle smuggled from Egypt in tunnels. Libya and Bahrain have also reported the SAT2 strain, though genetic analyses show the virus affecting cattle in Egypt is of a different lineage.

The origin of the disease in Egypt remains a mystery. According to Tibbo, while a similar strain was reported in 2007 in Sudan, the only way it could have come to Egypt is through the quarantine system in Aswan. But the virus was never reported in Upper Egypt and has spread mostly in the Delta region to the north. While this particular strain of the virus appears to share lineages with a virus in Chad and Niger, the way it made its way to the heart of the Nile Delta is currently a mystery.