This piece was written for Egypt Independent’s final weekly print edition, which was banned from going to press. We offer you our 50th and final edition here.

Journalism is becoming an increasingly dangerous and precarious profession in Egypt. Thousands of journalists risk life and limb on the streets while covering volatile events — often to find that their job security is also being threatened. In numerous cases, journalists are “rewarded” for their efforts by being dismissed from their jobs.

Al-Masry Media Corporation is the most recent employer to “reward” its journalists and employees with mass layoffs. Concerned with profitability, the company recently dismissed a number of its employees, with its closure of Al-Siyassy magazine in February and Egypt Independent this month.

While Egypt Independent is the most recent victim of closures and layoffs, a host of other newspapers and magazines — particularly independent and opposition publications — have also been shut down in recent years. Several of the remaining newspapers have raised the prices of their publications while cutting their budgets, and laying off employees.

Al-Siyassy and Egypt Independent follow in the footsteps of many including Al-Badeel, Al-Dostour and Daily News Egypt — the original versions — which have all been forced to shut down in recent years.

Khaled al-Balshy, Journalists Syndicate secretary and former editor of Al-Badeel newspaper, says that 13 papers have been closed down over the past few years.

“These closures have left some 350 journalists unemployed,” Balshy says.

Balshy adds that a total of 650 to 700 journalists, if not more, have been dismissed prior to and since the 25 January revolution two years ago.

“More closures are expected in the near future and more job losses are expected as a result,” Balshy says.

Burdensome profession

In Egypt and the Arab world, journalism is known as “mahnat al-mataeb” — the burdensome profession. Faced with physical danger, the threat of arrests, growing financial crises, the mismanagement of news outlets and rising unemployment — along with a host of other problems — Egypt’s journalists increasingly find themselves paying the price for these burdens with their own welfare and jobs.

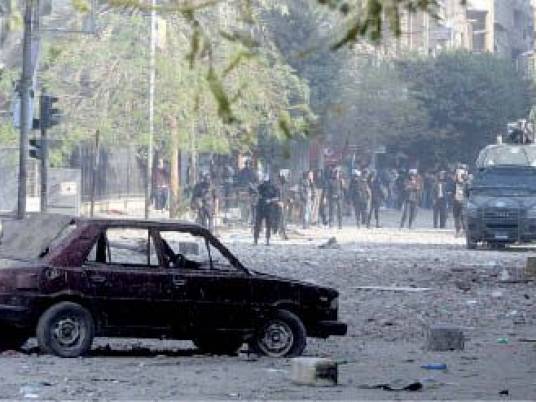

Prior to and since the revolution’s onset, journalists are continuing to risk their lives and physical safety while covering violent protests, clashes and uprisings.

Police shotguns have claimed the eyes of several journalists, while independent journalist Al-Husseini Abu Deif was shot dead outside the presidential palace in December, and journalist Mohamed Sabry faces a military tribunal for his work in Sinai.

Countless others have been beaten and arrested by security forces, assaulted by supporters of the ruling regime (outside Muslim Brotherhood offices and the presidential palace), and even attacked by the Coptic Orthodox Church’s boy scouts.

“Neither employers nor the Journalists Syndicate provide sufficient safety nets for journalists,” says Mohamed Radwan, a freelancer who used to work for Al-Dostour newspaper.

Radwan is one of nearly 100 journalists who have lost their jobs at Al-Dostour.

Egyptian journalists

The average salaries of full-time journalists in daily newspapers range from LE400 to LE2,000 per month. For internships and training, beginner journalists are typically not paid at all.

Moreover, the widespread practice of employing full-time journalists on part-time contracts serves to deny these employees their right to bonuses, promotions, insurance coverage, profit sharing (when applicable), job stability and the right to join the Journalists Syndicate.

“I’d been employed for five years at Al-Dostour, yet was not even offered a part-time contract,” Radwan says. “I was thus denied my periodic bonuses, insurance plan and end-of-service payment, along with all of my other rights.”

Only a minority of journalists are accepted into the Journalists Syndicate, Radwan adds.

“The syndicate neither serves the interests nor protects the rights of the majority of Egypt’s journalists,” he says. “The syndicate doesn’t care about our grievances, difficulties and daily suffering.”

Balshy says the syndicate has a membership of about 9,000 journalists nationwide, of which some 7,000 are still practicing the profession. Another 6,000 or more journalists are not syndicate members.

The syndicate’s bylaws are the problem, he argues.

“We must change syndicate bylaws,” he says. “It is becoming increasingly difficult for journalists to apply for membership.”

He asserts that the syndicate is supposed to protect all journalists, especially those beginning their careers and those who are denied full-time contracts.

“It should be a syndicate for all those who practice the profession,” he says.

Balshy concedes that, given present economic hardships, it may be more difficult for journalists to acquire full-time contracts.

“Nevertheless, the syndicate should strive to protect disadvantaged journalists, not merely those lucky enough to have full-time contracts,” he argues.

But administrative shortcomings, financial mismanagement and other social, economic and political factors continue to hinder the provision of full-time contracts for full-time work, Balshy says, and may lead to additional closures of news outlets in the near future.

With regard to the closure of Egypt Independent, the secretary of the syndicate states, “I generally attribute the closure to the lack of English-speaking readers in Egypt, low subscriptions, high expenses and mismanagement on the part of Al-Masry Al-Youm.”

Foreign journalists

While the average salaries of foreign journalists and Egyptians employed in foreign-language media outlets is nearly double that of local journalists, non-Egyptian journalists face numerous difficulties.

Foreign media personnel are not allowed membership in the Journalists Syndicate. Non-Egyptian journalists are can only register themselves at the state-controlled Foreign Press Association (FPA).

The FPA provides these non-Egyptians with work permits and journalist IDs, which are subject to selective renewals.

Foreign journalists who have fallen out of favor with the FPA have been slapped with travel bans, criminal investigations and, in many cases, are denied re-entry into Egypt. Foreign journalists also face a rising tide of xenophobia.

Earlier this month, Dutch journalist Rena Netjes was arrested and handed over to police, who accused her of “espionage” and “disseminating Western culture.” She was released, but later charged with not having a valid work permit.

Wael Tawfiq, founding member of the Independent Egyptian Journalists’ Syndicate, says the group accepts foreigners in the syndicate, but only as affiliates.

“They do not have the right to vote in syndicate elections nor to nominate themselves. On the other hand, the official [Journalists] Syndicate does not accept foreigners under any condition,” Tawfiq says.

Tawfiq says his independent syndicate claims a membership of some 600 people, nearly all of whom are Egyptian.

“We don’t demand full-time contracts as a prerequisite for membership, only an archive of published materials in a news outlet based in Egypt,” he says.

In what he calls an “absence of safeguards” from employers and the official syndicate, the independent syndicate stands “for the defense of journalists’ rights through all stages of their work,” and attempts to protect members from punitive measures.

However, his syndicate does not have an emergency fund, nor does it provide unemployment assistance.

The official Journalists Syndicate has filed lawsuits against both the Independent Journalists Syndicate and the Egyptian Online Journalists Syndicate, both of which were established in 2011. The official syndicate claims it is the sole association legally entrusted with representing and organizing Egyptian journalists.

Bleak outlook

Radwan says Egypt’s press freedoms and right to free expression are being “eroded” by the Muslim Brotherhood.

“Plus, we are expecting more economic problems in the media industry and in the general economy as a whole,” he says.

Radwan expects higher unemployment rates for journalists and media employees, along with fewer independent and opposition news outlets.

Tawfiq also expects more media outlets to close, due to both the Brotherhood’s attempts at “gagging” the media and the faltering economic conditions throughout the country.

“We’ve seen how President Mohamed Morsy’s supporters have besieged the [private] Media Production City. We’ve witnessed an unprecedented number of lawsuits against critical journalists, the appointment of regime loyalists to the top state-owned publications and channels, and the court-ordered closures of several satellite TV channels,” says Tawfiq.

He says he expects fewer job opportunities, lower salaries for full-time journalists and decreased rates for freelancers in the future.

Additional English-language publications and websites are expected to soon close. These closures will leave the state with a near monopoly on foreign-language news publications.