In "Heliopolis," Ahmad Abdalla’s fiction debut, a seminal scene depicts a couple gazing at each other for a moment in a noisy hypermarket sprawling with LCD screens, fans, and kitchen machines.

Their ominous gaze left viewers entrapped in a state of sudden remembrance of how the difficulties of everyday life have inhabited them so strongly that they are no longer conscious of it.

Because it is engaging on that level, "Heliopolis" is good film, but it missed the chance to make a unique proposition. "Microphone," Abdalla’s newer work (which was awarded the Tanit d'or at the Carthage Film Festival), fills this void. While still addressing certain contemporary hardships, "Microphone" is choreographed around the enchantment that unfolds with artistic practice and expression, an enchantment that serves as a point of departure and a new beginning.

Built around the stories and artworks of Alexandrian underground musicians, graffiti artists and filmmakers, "Microphone" brings itself forward as a community-based work, at the heart of which lies an interesting process of art making.

With the vast majority of the film’s actors coming from a non-acting background and a script the result of their collaboration, the film entangles itself in the layered realities that its characters come from. The result is a semi-documentary style that remains close to reality while creating a situation that embodies a dream, an imagination, a proposition.

What if we bring all these artists together?

The proposition comes from Khaled (Khaled Aboulnaga), an engineer who returns to his home city only to find his beloved planning to leave herself. While attempting to interrogate this return to a city that has undergone so much change, he immerses himself in rediscovering it through the lens of a thriving alternative art scene.

That scene is in a state of crisis for being constantly pushed to the margins by the mainstream. Abdalla orchestrates their re-positioning in his work. In "Microphone," those artists become center stage; they redefine Khaled’s character in the film. The main story with his bygone beloved subtly retreats, with Abdalla introducing that storyline via a rendezvous that moves backwards, ending at the beginning, when things were simple, pristine and hopeful.

Meanwhile, Khaled’s quest to create a collective of Alexandria’s underground art scene ascends. He identifies them, gets to know them, makes a party for them and tries to throw a street concert for them.

When security prevents Khaled and the artists from formally inhabiting the street, he puts forward a more urgent crisis, engaging with all those who have reclaimed the streets with their artwork, words or dreams. In a way, it’s a line of institutional critique that adds depth to the film’s proposition.

Abdalla puts a semi activist hat on. He says his main quest is to promote those artists he met in Alexandria and that, at the onset, he wanted to make a documentary about them. In the film itself, Abdalla interrogates the function of documentary art through a dialogue between Salma (Yousra al-Lozy) and Magdi (Ahmed Magdi), both filmmakers venturing to make a film about Alexandria’s underground artists and struggling to position themselves there.

This inspiring conversation aside, Abdalla says he shifted to fiction because he wanted the film to be more accessible and to attract a producer.

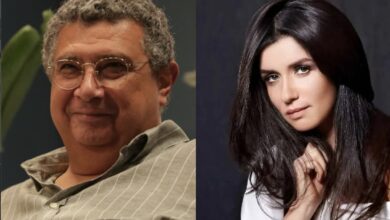

Besides attracting a co-production deal with Mohamed Hefzy and Khaled Aboulnaga, both of whom are firm believers in Abdalla’s quest to promote the artists, the picture does a good job introducing Alexandria’s lesser-known art scene.

We see Alexandrian band Masar Egbary’s rising stardom as well as Mascara, an all-girls metal band whose members wear masks when they perform in Alexandria to hide from their disapproving parents.

We're also introduced to Aya, a graffiti artist who takes to the streets as a reaction to, and protest of, her exclusion from the gallery world. “I will go to the street, do what I want there, my way, and no one will tell me how. No one would talk to me about budgets or concepts. And at the end, all those walking in the street will see my work,” she says in a line that raises a lot of questions about public art, and where creativity starts and curating stops.

The film also shows us San Stefano, Alexandria’s busy district with a community of hip-hop and break dance artists. Hip-hop is candidly used by the group Nosair in describing an everyday condition and relaying it by calling on humor.

The film opens with the hip-hop lyrics of Nosair: “Welcome to Alexandria, when you come this way, from Abu Qir to Amreya, the best for costal towns.” It moves on to praise the city and its people for being real and to celebrate their goodness, smartness and liveliness.

The words of the band are jovial, humorous and honest. But, most importantly, they speak to a persistent and lagging literature that only constructs a nostalgic image of Alexandria as a formerly cosmopolitan city that is now a much more populated, and deteriorating, city.

Besides being negative, this rather plain narrative (that also extends to Cairo), imposes a past that was not lived by the most of its people. While it’s important to remember that past, this narrative detaches itself from the realities of the present.

Nosair and others in the underground art scene in Alexandria reclaim the narrative of the city and reintroduce it in light of the minutiae of its backstreets and underground world that, rather than decaying, have become spaces for homegrown creativity that speak to power, to tradition and all what lies in between.

"Microphone" wanders into those spaces and comes back with a story worthy of your undivided attention.