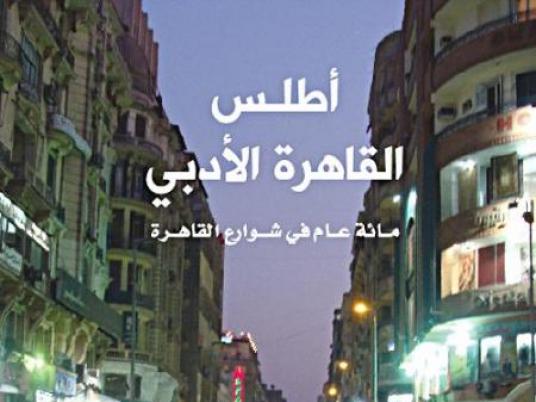

We all learn about cities through fiction, from the experiences of the stories' narrators and protagonists. Even when we live in the very same city where a story is set, we can sometimes develop new relationships with the places featured. Looking at Cairo through the lens of literature and tracing how authors wrote about the Egyptian capital in modern times is the crux of “The Literary Atlas of Cairo: One Hundred Years on the Streets of the City.” Dar al-Shorouk has recently published an Arabic translation of the book by literary critic Samia Mehrez.

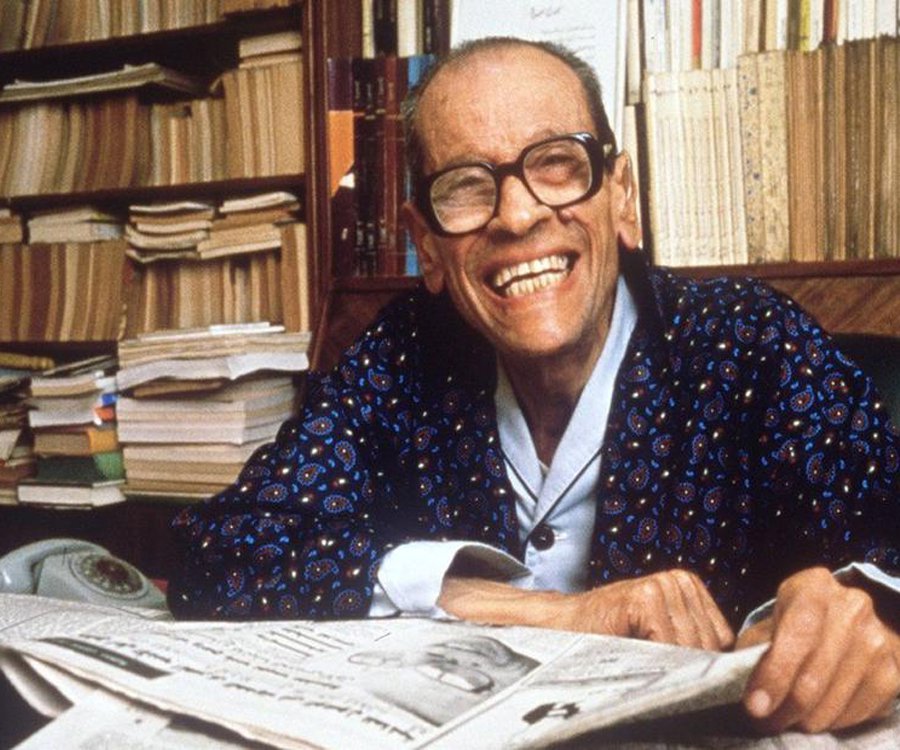

Inspired by Franco Moretti’s pioneering study “Atlas of the European Novel, 1800–1900,” Mehrez introduces the geography of Cairo’s streets through snippets from 100 novels by 58 Egyptian and foreign writers. We find stories about Cairo, its streets and the memories of its inhabitants by veterans like Naguib Mahfouz and Yahya Hakki, side by side with those of French language writers Andree Chedid and Robert Solet, and even younger writers like Ahmed al-Aidy and Mohamed Salah al-Azab. The novel as a form is always related to the city, writes Mehrez. And readers in turn easily relate to her selections, even if they have not read some of them before.

In her introduction, Mehrez cites the vision of French philosopher Roland Barthes in "Seminology and the Urban" about the city as a discourse and language that inhabitants engage with. "The city is not a physical presence that writers reproduce; rather, the city is a construct that continues to be reinvented by its inhabitants — in this case its writers — each according to his or her experiential eye and personal encounter with it," writes Mehrez.

She presents her selection through five main chapters, each exploring the relationships between the texts and the city. To introduce "The City Victorious," Mehrez uses Mahfouz's "Children of the Alley" and "The Time Travels of a Man Who Sold Pickles and Sweets" by Khairy Shalaby. The narrators in the novels, like the authors, tell the stories of their streets and alleys, luring readers in. She then starts to map the city, discussing how different authors dealt with prominent places in Cairo. Old, populous districts are presented in stories like Mahfouz’s “Midaq Alley,” and Hakki's “The Lamp of Umm Hashim.” The craftsmen who live there often fight the modern world in vain, like the munshid of the traditional coffee shop who sees the radio as his enemy. Other writers in the book take us through downtown, Heliopolis and Zamalek, and then the less affluent districts of Kit Kat or the garbage collectors' neighborhood in Hany Abd El-Moreed's novel “Kyrie Eleison.”

In the “Public Spaces” section of the book, Mehrez tries to put her hand on the landmarks of Cairo and the symbolism writers attach to them, such as the pyramids as a mystic sign in Gamal al-Ghitany's “Pyramid Texts.” The Citadel is cast as a sign of oppression in Sonallah Ibrahim “Cairo from Edge to Edge," which was built by one of Salah al-Din al-Ayyubi's aides, Qaraqush; in modern times it became a prison for political opponents. As for Anne-Marie Drosso, she takes us through "Cairo Stories" to the Mugamma building, emphasizing it as a symbol of state bureaucracy. In “Private Spaces,” we look inside the intimate worlds of Cairene characters. We see Amina’s small world as her house in Mahfouz’s “Cairo Trilogy,” and how residents deal with “The Yacoubian Building” in Alaa al-Aswany novel.

In addition to the public and private spaces that Mehrez explores, she devotes a whole section to transportation in "On the Move in Cairo." The means people use to get around their city form one of the ways they relate to it, she argues, and these methods change over time yet also exist simultaneously in Cairo, from horses to taxis, and from trams to metro lines, and now microbuses and tuk tuks. She traces the stories that happen on board: salesmen sell women’s accessories and religious booklets inside passenger carriages and microbuses play religious sermons and songs. Even sexual harassment incidents on buses are included, through Raouf Mosad's novel “Ithaca.”