“I’ve been watching this film for three days and I haven’t been the same,” said Moukhtar Kocache. “Walking in the streets of Cairo hasn’t been the same.”

The Contemporary Image Collective is currently running a series of talks and screenings called “Battles of Images” over four evenings. Curated by Palestinian artist Shuruq Harb, the series looks at news photography as one of the region’s biggest exports and examines “the visual culture resulting from shifts in photojournalism towards systems of aid.”

The first event was a screening of Dutch artist Renzo Martens’ “Enjoy Poverty” and a discussion between Kocache and Asunción Molinos Gordo. Kocache is an arts consultant and curator who was program officer at the Ford Foundation’s Cairo office from 2004 to 2012, and Molinos is an artist whose work considers the politics of global agriculture and involves incredibly precise duplications of visuals — for example, those of Egyptian fast-food restaurants for her recent “El Matam El Mish-Masry.”

Martens’ sort-of-documentary also involves a kind of duplication — not just of visuals in his case, but of the act of exploiting people in Congo. He plays a character, Renzo, who goes to Congo to determine whether poverty is its largest natural resource, and to encourage Congolese to take ownership of it. The film is angry, unflinching, obnoxious, and certainly not a comprehensive investigation into the subject.

Near the beginning of the film a World Bank representative retorts that poverty is not a natural resource, but “a shared defeat for the international community.”

But as the story develops, incidents and comments build up to show how Congo’s poverty is a massive industry whose beneficiaries are not necessarily Congo’s poor. We see the malnourished children of employees of foreign-owned plantations. An aid worker is challenged to consider why all the plastic sheeting in a refugee camp has UNICEF logos. It’s mentioned that 70 to 90 percent of some countries’ aid flows back to the donor country. An Italian AFP photographer is forced to explain somewhat ineptly why a photograph he takes belongs to him and not the people he photographs.

As well as presenting these powerful images and revealing comments, Martens self-consciously plays the white savior going down the dark river. Dressed in white, he periodically preens and sings for the camera while Congolese people carry his stuff. Kocache said afterwards that “his physique doesn’t help him — he has a sort of smart-ass look to him,” but it seems Martens positively utilizes this image — a cross between Marlon Brando and Klaus Kinski.

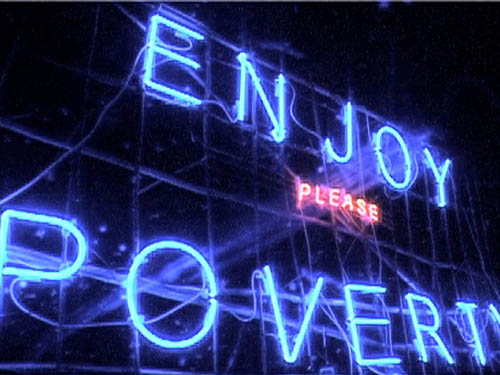

In this role of “enlightening” the locals he carries round a generator and a huge neon sign and erects it every now and then. It reads, “ENJOY POVERTY” in blue with a ridiculous small “PLEASE” flashing next to it in red. “For the audience, it needs to be English,” he explains.

Martens meets some Congolese photographers who take photos of celebrations for about US$1 profit per month. The AFP photographer, he reckons, gets US$1000 per month taking pictures of misery — or, “let’s be more specific,” he says: raped women, corpses, and malnourished children. “They’re only interested in negative stories, it’s supply and demand,” the photographer had said. “It’s a market out there.”

“The Americans know what they need,” agrees one of the men that Renzo is instructing. Renzo brings them to dying infants and dead people, encouraging them to see these subjects aesthetically, using light on jutting ribs to capture the most iconic, hard-hitting image.

The end of what Kocache called this “act of futility” — did the photographers end up worse off than they were before, he wondered — the group attempts to enter a Médecins Sans Frontières hospital to photograph patients. We see the doctor refusing to let them in, though he acknowledges that the international press corps are allowed because they are “here to make news not money.” Later, Renzo reads a letter asking the UN to revoke his press access, due to his “ill-placed” project that has “caused offence.”

Poverty attracts money, donors, charity, Renzo informs the people he meets. You’re not the only beneficiaries, but you have to be endlessly grateful. If you wait to be happy until your salary goes up you will be unhappy all your lives, because “we in Europe” don’t want cotton, palm oil, cocoa, and so on to be more expensive.

One of the powerful elements of the film was it showing the blazing anger of those people who are stuck in a situation in which they cannot feed their children to keep them alive. In the discussion afterwards, Molinos suggested that Martens is showing that people’s oversimplified ideas of poverty are wrong.

Molinos said it made her ask herself, as an image-maker, “Who are we producing images for?” and “What images are we hiding?” She pointed out that images of Egypt now seem to have one profile — gasmasks, teargas — and asked if is this a distraction from the other things going on in the political arena. She suggested we interrogate our motives, ask ourselves if we just want to be invited to biennales (which she called a “heaven of glamor”).

Harb also said, “It becomes most hard to talk about when we talk about it as art, the art market.”

Indeed, it would be easy to just critique the film’s flaws, or its form. But that would be to pretend that its basic message — that poverty is more profitable for aiders than the aided — is incorrect, or that if correct, it should stay in the realm of media studies. Perhaps it would be easier to dismiss it, more easy to just be offended by its form, if one saw it in a gallery in London, where you don’t really have to deal with poverty and representations of it every day?

Kocache pointed out that the film also comments on “the absurdity of the current art system, its priorities, the funding schemes for it.” He suggested that the art establishment now, unlike for example New York in the 1980s, is opposed to art and activism, is overly concerned with personality, would prefer an artwork to only have one function.

The film exasperated some audience members in different ways. One was angered by the portrayal of the doctor, who, he said, is risking his life. Someone else angrily pointed out that the idea that starting in Congo we go into the heart of darkness to find out about ourselves is extremely problematic — even though Martens seems to be confronting head on this tradition of Africa being used as a foil to Europe.

Another criticism put forward during the discussion, which varied in terms of contributions from trite (“It makes me sad”) to more nuanced and sophisticated, was that there is “no outside” of the artist’s vision (he is of course also hiding certain images), which is totalizing. He creates a moral landscape that is flat — like a package, as Harb put it.

For Kocache, however, the film helped him “stop pretending to be making a difference” and he said that the most important thing was that “it leaves the idea of personal responsibility hanging there.”

Kocache added that this is a time of confusion, when democratic social welfare states based on enlightenment ideas have failed all over the world, and as such is a potential moment for reformatting power dynamics. “It’s been years since I felt that so many people are willing to kick and scream,” he said — and not care that they won’t be invited to the biennales.

"Battles of Images" continues on Tuesday at 7pm with a session on the current status of documentary imagery produced about Egypt, and on Wednesday at 7pm with a lecture performance by Harb titled "In response to the Palestinian Authority." All events take place at the Contemporary Image Collective, 22 Abdel Khalek Tharwat St., downtown, Cairo.