Burundi on Monday officially joined several fellow upstream countries in an alternative Nile Basin initiative, allowing the pact to come into force without Egypt’s approval.

Tensions in the Nile Basin between upstream and downstream countries have long been a key diplomatic issue for Egypt.

Six upstream countries have so far signed on to the Entebbe-based Nile Basin Initiative (NBI), which will establish the Nile Basin Commission, a body mandated with deciding on river projects in basin countries.

“Burundi took advantage of recent political turmoil in Egypt and hurried to sign the initiative. It knows that Cairo has its hands full with domestic issues after the removal of [former president Hosni] Mubarak,” said Amany al-Taweel, an expert in African affairs at the semi-official Al-Ahram Center for Political and Strategic Studies.

After 18 days of massive protests, sit-ins, marches and civil disobedience, Mubarak was forced on 11 February to leave the office he had occupied for 30 years.

In November, after a meeting with Mubarak, Burundian Presidential Adviser Mohammad Rokara had said that his country would “never take a position that conflicted with Egypt's interests.”

Egypt's population of some 85 million draws about 90 percent of its water needs from the Nile. Officials, for their part, warn that the alternative water agreement would be unable to provide Egypt’s growing population with its water needs beyond 2017.

Critics have often blamed Egypt’s ousted president for ignoring Africa and for failing to deepen Egypt’s strategic ties with the states of the Nile Basin.

Experts also blast Egyptian foreign policy for being slow to deal with perceived threats to the strategically-important river. They accuse it of encouraging Nile Basin countries to seek alternatives to the historical agreements that have regulated usage of Nile water resources for most of the last century.

“Egyptian diplomats go everywhere except Africa. Mubarak was always in Sharm El-Sheikh while his foreign minister [Ahmed Abul Gheit] was touring Europe. There was no interest whatsoever in the African continent,” said columnist and pan-Arab political activist Ahmed al-Gamal.

“It’s time to reconsider Africa as a priority in our foreign policy. We can provide technical assistance for electricity projects and farming expertise on the basis that we are equal. There shouldn’t be a sense of Egyptian superiority,” added al-Gamal.

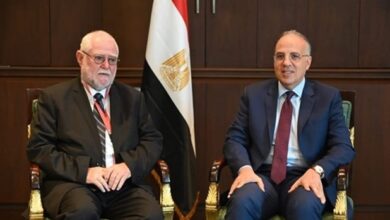

On Tuesday, Hussein al-Otaify, Egypt’s newly-appointed minister of irrigation and water resources, held an urgent meeting with other concerned state bodies.

Al-Otaify has said his ministry would draft an “urgent plan of action” in order to deal with the Nile issue, stressing that Egypt planned to take part in several bilateral projects with Nile Basin countries while calling on upstream states to preserve “Egypt’s historical rights in the Nile.”

Last year, after a decade of talks, four upstream basin countries–Uganda, Rwanda, Tanzania and Ethiopia–signed a pact allowing for what they said was a more equitable use of Nile water.

Under the Cooperative Framework Agreement, Ethiopia intends to build dams and export power to neighboring countries, while also establishing a host of irrigation projects.

Egypt and Sudan, both of which condemned the pact, have argued that their respective water supplies would be dangerously reduced if upstream countries were allowed to divert the flow of the river without multilateral consultation.

Egypt says that all Nile Basin countries must approve any initiatives involving the river to ensure that its traditional share remains unaffected, in accordance with international treaties signed in 1929 and 1959.

In 1929, imperial Britain, representing a number of Nile Basin countries, signed a deal with the Egyptian government for the distribution of Nile water. The terms of the treaty granted Egypt 55.5 billion square meters of water annually, out of the estimated 84 billion square meters that flow through Sudan every year.

East African countries have long complained about the negative effects of the colonial-era 1929 treaty, which allows Egypt to veto any irrigation or hydro-power projects proposed by upstream countries.

Under a 1959 Nile water agreement with Sudan, Egypt receives the lion's share of Nile water. Sudan, the next largest recipient, is allotted 18 billion cubic meters per year. This means that the two downstream countries account for more than 90 percent of all Nile water.

Such agreements have effectively given Egypt veto rights over all upstream projects.

“Egypt has applied a strategy that puts emphasis on the authority and validity of the traditional treaties of 1929 and 1959,” said al-Taweel.

Egyptian experts argue that disputes between Egypt and Nile Basin countries are of a "technical" rather than “political” nature. They assert that there is more than enough Nile water for all countries of the Nile Basin.

“The foreign policy of post-Mubarak Egypt will not abandon the strategy of commitment to the traditional treaties, but Cairo will show more interest in cooperating–economically and strategically–with other Nile Basin states,” al-Taweel said.

While upstream nations have refused to change the newly signed Cooperative Framework Agreement as per Cairo’s requests, the NBI scheduled an extraordinary meeting in January aimed at changing Egypt’s mind about the accord.

The meeting, however, was cancelled due to Egypt’s popular uprising, but is now slated to take place in Nairobi later this month.

Moreover, an African summit on Nile water usage, originally scheduled to be held in the Ugandan capital of Kampala in January, was also cancelled as a result of recent political turbulence.