Egypt has a rich biodiversity and a vast number of animal species found on its soil. But in spite of this richness, Egypt’s wildlife is threatened by ongoing smuggling and illegal hunting, while captive animals suffer from a range of ill treatment that goes ignored by officials.

The law for the protection of wildlife, implemented in 1994, prohibits the killing of threatened species native to Egypt. The law was amended slightly in 2009 to protect all threatened species in Egyptian territory.

A total of 28 protected areas, scattered across Egypt, protect and control the habitat of certain wildlife.

“The biggest threat for wildlife in Egypt is hunting for bush meat,” says Dr. Sherif Bahaa Eddin, an ornithologist and member of the NGO Nature Conservation Egypt. “People hunt owls, quails, whatever they can catch for food, because–we can’t deny–once plucked all birds look the same!”

“Sometimes the hunting of certain bird species is a persistent tradition,” he continues, “and then it is all the more difficult to curb the phenomenon.” Bahaa Eddin gives the example of the golden oriole, a bird that migrates through Egypt in September which locals in Bahariya shoot in great numbers.

Animal welfare activist Dina Zulfikar names falcons, foxes, turtles, oryx and gazelles as Egypt’s most endangered species. She explains that until recently, initiatives by NGOs involved in wildlife protection merely involved “taking the picture of a dead animal and then circulating it on the internet, asking for international help.”

Many people involved in wildlife conservation mention the successful initiative of the Hurghada Environmental Protection and Conservation Association (HEPCA) to protect dolphins. HEPCA signed an agreement with the Red Sea Governorate, the Egyptian Environmental Affairs Agency (EEAA) and the National Parks Authority of Egypt that resulted in the creation of the Samadai Reef protected area.

Beshoye Morise, an environmental researcher for the EEAA, participated in a project to protect the spinner dolphins in Samadai, an area 5km south of Marsa Allam also know as the “Dolphin House.”

“Before the joint intervention to limit the number of visitors allowed to the dolphin house, around 2500 people a day would disturb the dolphin community, forcing some dolphins to abandon their habitat,” says Morise.

The various areas of the offshore reef which is the dolphins’ habitat were easily accessible to the public and the dolphins had no space to rest until it was decided to set up zones to ensure the dolphins are left in peace.

“Today the number of specimens range from 80 to 112 and are not decreasing anymore,” Morise says. The three most endangered marine species among the 13 that inhabit the area are whales, dolphins and sharks.

“Since 2005 and the passing of the new law prohibiting the fishing of sharks, we implemented a patrolling system to monitor the area and deter fishermen,” explains Morise.

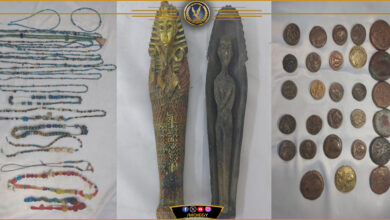

But illegal hunting or fishing for human consumption is not the only threat facing Egypt’s wildlife, as almost any animal can be obtained on the local black market.

“There is a rising demand among wealthy people, both locally and in the Gulf, for exotic animals to match their high-end lifestyle,” Zulfikar says with contempt, adding that the illegal trade of wildlife poses a huge threat to Egypt’s threatened species.

The smuggling of endangered species is thriving as the limited funding allocated by the government and international organizations for the protected areas is not sufficient to ensure the complete protection of wildlife in their habitats.

And it’s not just Egypt’s own wildlife that is at risk. Traffickers come from as far as Nigeria and Cameroon to smuggle great apes through Egypt, according to Zulfikar.

“Egypt’s location is very central and many traffickers smuggle animals through its border, from Africa to Europe and the Middle East,” she says, and briefly relates some stories that made headlines during the past few years.

“In 2001 Egyptian officials at Cairo Airport drowned an illegally transported chimpanzee and a gorilla from Africa in a vat of chemicals. Recently a lion from Libya was confiscated, and stories of passengers stuffing their bags with baby crocodiles, reptiles and chameleons are no longer sensational,” Zulfikar says.

On the other hand, the treatment of captive animals in places such as Giza Zoo, has improved–relatively–following initiatives such as the “Revitalize the Zoo” project launched in 2007 by Zulfikar.

“With professional volunteers we established a list of short, medium and long-term initiatives aiming to improve the condition of the zoo. Thus we met with various delegations from the African Association of Zoos and Aquaria (PAZAAB), as well as the World Association of Zoos and Aquarium (WAZA), in order to set our work priorities,” she explains.

All agreed on the fact that the enclosures for bears and chimpanzees required immediate attention and “a water cooling system was installed to cool the bears instead of a big block of ice that would take seconds to melt,” Zulfikar says.

The inside area of the chimpanzees’ enclosure had ropes, hammocks and fans added to it, and their grouping was rearranged after a long study by the zoo veterinarian.

“One of our long-term projects is to reduce the number of lions. A lion lives an average of nine to 15 years in captivity, and we will not replace them, because its best to have a greater variety of species and less representatives of each species,” says Zulfikar.

The main aim however was to raise awareness among children and parents when they come to the zoo.

The team of volunteers from “Revitalize the Zoo” meets every last Friday of the month from 9:30 to 11:30 AM to educate visitors on the importance of the environment by organizing sessions on biodiversity, the food chain, hunting and birds.