Many would expect that, as an organization ascending to power from political isolation, the Muslim Brotherhood would engage in a foreign policy spree of weaving new relations with both old and new partners.

Idealists would certainly expect that, as an organization coming to power following a popular revolution, the Muslim Brotherhood would enact radical changes to foreign policy.

But in practice, neither expectation has been met.

For some analysts, Egypt’s entrenched global relations are too intricate to be undone, tied as they are to questions of regional security. For others, domestic unrest, coming in multiple forms and from various sources, poses an impediment to Egypt’s development of an astute and creative foreign policy.

Initial gestures to deepen relations with non-traditional partners (since taking office President Mohamed Morsy has visited Africa twice and China once) suggested that the Brotherhood would take Egyptian foreign policy in new directions. But many observers agree, all in all, that over the last six months the Muslim Brotherhood has reproduced Mubarak-era policies, and that it will continue to do so in the year to come. Despite this continuity, Egypt’s allies are adapting to the country’s new leadership in different ways.

The Gulf

A strong bond ties Egypt to the Gulf, based on both being counterbalances to Iran’s perceived Shia expansion in the region. Yet the configuration of political Islam in Egypt, in the form of Muslim Brotherhood rule, remains disconcerting for some Gulf players.

Sultan al-Qassemi, a columnist on Gulf affairs, argues that the Gulf states, save Qatar, are concerned with the Egyptian Brotherhood’s choices and extent to which it will support regional Brotherhood offshoots in Jordan, Yemen and Syria.

For example, the United Arab Emirates is expected to put alleged affiliates of an unauthorized Muslim Brotherhood cell on trial in 2013. “How their Egyptian counterparts react will determine relations between Abu Dhabi and Cairo for years to come,” Qassemi says.

Israel

Morsy’s successful brokering of a truce between Israel and Gaza following November’s attack on the Strip was a relief to those concerned about the new Islamist leadership’s antagonistic rhetoric. Banking on the organic ties between the Muslim Brotherhood and the militant Hamas government in Gaza, Israel may believe that Egypt’s new leadership will be an even more efficient security contractor than the Mubarak regime.

But the truce leaves the right-wing Israeli government concerned about the state of the peace accords and the perceived rise in threats from militants in the neighboring Sinai Peninsula.

Despite the truce, Iman Hamdy, a professor of political science at the American University in Cairo, believes that the most Egypt can do for Gaza is provide moral support, as it did during the latest Israeli attack, and open its border with Egypt.

The United States

The US appears to be waiting to see how events in Egypt unfold, considering the unknown consequences of the passage of the constitution and upcoming parliamentary elections. For now, the state of bilateral relations remains confused.

“The Egyptian opposition falsely imagines that there is a deal between the United States and the Muslim Brotherhood. In fact, America wants to know who it should deal with,” Michael Hanna, a fellow at the New York-based Century Foundation, argues. “Even if it prefers to deal with a secular opposition, it made mistakes in the past in not dealing with Islamists, and so now it is trying to work with them.”

Traditional interests will continue to define the Egypt-US relationship, with regional security at the top of the list.

“I expect relations between Egypt and the US to continue to be driven by the principle that in politics, there are no permanent friends, only permanent interests,” says Elijah Zarwan, an analyst with the European Council on Foreign Relations.

“So long as certain conditions are met, the US foreign policy establishment seems willing to back whichever side they think will win, which for the moment remains the elected government,” he continues.

But Hanna contends that while America respects the results of the ballot box, this doesn’t mean that it is pursuing the same policies it practiced with the Mubarak regime, whereby it closed its eyes to repression of the opposition Muslim Brotherhood in return for concrete foreign policy concessions. “[The US] knows the Egyptian people will not close their eyes to repression,” Hanna says.

Similarly, Zarwan argues, “I don’t know if the Brotherhood is fully aware of the problems that await it from the US Congress…they may confuse the Obama administration with Washington.”

Turkey

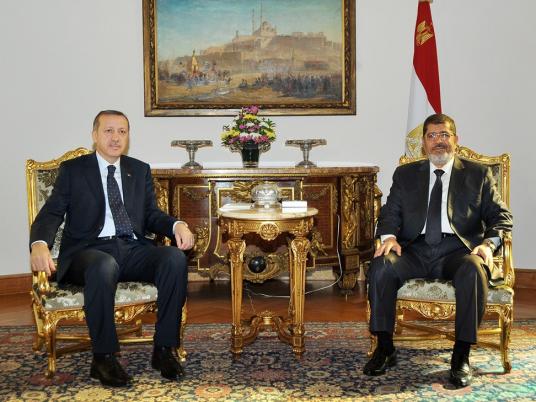

Egyptian-Turkish relations have seen the first signs of rapprochement. Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan took a positive stance toward the Egyptian revolution, and Turkey repeatedly offered assistance to Egypt, in what several Turkish scholars describe as a quest to deepen Turkey’s position and influence in the region.

Meanwhile, Turkey’s Justice and Development Party serves as a source of inspiration for Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood in the way that it is a religious party — variously described as moderate and modern — that has deployed its control gradually over the country, as well as cultivated productive foreign relations.

Mostafa al-Labbad, director of Al-Sharq Center for Regional and Strategic Studies in Cairo, says that while there is no fundamental change in Egypt’s policy toward Israel and the United States, and no serious reconciliation with Iran, the one clear change might be the consolidation of links with Turkey.

But while the warming of Egyptian-Turkish relations may seem to be a win-win for both parties, Hanna sees major ideological differences between the Justice and Development Party and the Brotherhood’s Freedom and Justice Party.

“Religion plays virtually no role in political and social life in Turkey, while religion is everywhere in Egyptian society. Erdogan’s party and the Muslim Brotherhood are different,” Hanna says.

Indeed, Erdogan’s statements during a recent visit to Cairo that secularism is the most appropriate form of government attracted stinging criticism from the Muslim Brotherhood and Salafi groups.

Given these obstacles, developments in bilateral economic relations are more likely, particularly given the expanded regional role that Turkey seeks to play and its expressed support for Islamist movements.

This piece was translated from Arabic by Sarah Carr.