When a suicide bomber blew himself up in a Cairo church a week ago, it marked a bloody escalation by Egypt’s jihadi militants, raising fears that an insurgency which for years largely focused on fighting in the Sinai and killing policemen may now turn to unleash attacks on civilians in the country’s capital.

A stepped up campaign by militants linked to the Islamic State group would be a heavy blow to a country trying to rebuild a wrecked economy and revive a vital tourism industry. The prospect is already spreading terror among Egypt’s Christians, who could be a main target.

In fact, the militants may use Christians in an attempt to enflame sectarian divisions in Muslim-majority Egypt, following the strategy of the Islamic State group in Syria and Iraq. By targeting the minority community, the group may be betting it can sow chaos and undermine the government of President Abdel-Fattah el-Sissi while avoiding indiscriminate bombings that kill fellow Muslims and bring an even more furious public backlash.

“They are framing justification for sectarian violence in Egypt in the same way they do it in Syria and Iraq,” said Mokhtar Awad, research fellow in the Program on Extremism at George Washington University.

A storm of attacks on civilians would be a frightening change for Egypt. Despite continued political unrest since 2011, Cairo and Egypt’s other cities along the Nile Valley have largely been spared such mass mayhem, even as Iraq, Syria and neighboring Libya have collapsed into chaos.

Extremists linked to the Islamic State group have been waging an insurgency in the Sinai Peninsula in brutal fighting with soldiers and security forces. In Cairo, they have carried out small-scale attacks on policemen and soldiers, as well as assassinations of officials, but rarely mass bombings.

In the past two years, security agencies succeeded in breaking up multiple militant cells outside of Sinai, aiming to keep the insurgency bottled up in the peninsula. Northern Sinai is a hotbed of militancy with plentiful weaponry. Last year, the militants are believed to have smuggled a bomb on to a Russian jet leaving the Sinai resort of Sharm el-Sheikh, downing it in an attack that has devastated tourism there.

But weapons and explosives are easily found across Egypt and can be smuggled in through the porous western border with Libya, a failed state where militias hold sway, said author and Sinai expert Mohannad Sabry.

“It’s a sprawling hub for explosives like TNT, just take a look at all the improvised explosive devices going off in Sinai and that the government claims it has seized — we are talking tons,” he said.

El-Sissi has fashioned himself as the leader of the fight against Islamic militancy in the region, portraying his crackdown on Egypt’s previously ruling Muslim Brotherhood as part of that wider battle. The new attack could be a move by militants to shake confidence in him at a sensitive time, after introducing painful economic reforms.

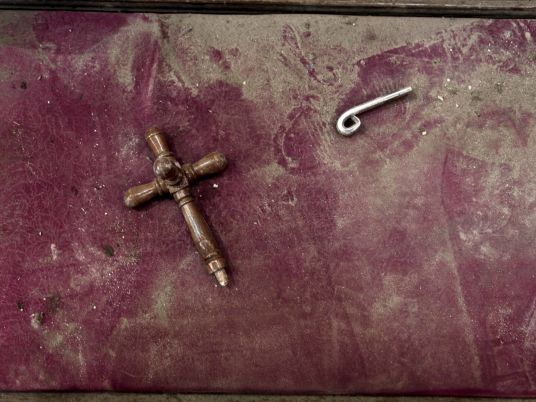

Last Sunday’s suicide bomber hit a church linked to the main cathedral of Egypt’s Coptic Christian Church, ripping through a crowd of mainly women worshippers, killing at least 26 and wounding dozens more. It was the deadliest such attack on Christians in years, recalling a 2011 suicide bombing at an Alexandria church that killed more than 20.

The government said Sunday’s bomber was a former supporter of the Brotherhood who joined militants. Later, the Islamic State group claimed responsibility.

Egyptian officials, however, have kept their focus on the Brotherhood, the Islamist political movement whose leader, Mohamed Morsi, was ousted from the presidency by the military in 2013. On Monday, the Interior Ministry said exiled Brotherhood leaders provided “financial and logistical support” for the church bombing.

Spokesmen for the Interior Ministry, responsible for police, as well as the Foreign Ministry, did not respond to requests for comment on whether they believed the bombing signaled the start of a wider campaign.

But a recent uptick in attacks has shown how violence has evolved the past two years. New groups such as one known as Hasm have emerged, launching high-level assassination attempts and attacks on security forces in mainland Egypt, including one that killed six policemen outside Cairo last week.

The militants could unleash a wider, indiscriminate campaign of violence, including against tourist sites — though tourism already is low. But they run risks in broad mass attacks. Egypt is more homogenous than Iraq and Syria, with virtually no Shiites. An Islamic militant campaign in the 1990s against the population as a whole produced mass resentment rather than turning the people against their leaders, and IS has been cautious of repeating that.

More likely, they could be trying to push the security agencies into mass arrests or abuses that could stoke resentment and further radicalize some.

In the aftermath of the bombings and at the ensuing funerals, many Christians shouted angry anti-government slogans, echoing a long-standing charge that the government’s security state is neglecting the most vulnerable segment of the population — theirs. El-Sissi himself has denied the church bombing was due to a lapse in security.

“In the present context, any attack on Egypt’s Christians is bound to both embarrass the government and its pretense to restoring law and order and erode popular support for the el-Sisi regime,” wrote Michael Hanna, a senior fellow at the U.S.-based Century Foundation. “But more importantly, those effects can be achieved while not risking broad-based backlash, with Egypt’s ingrained sectarianism insuring that outrage remains real but limited.”