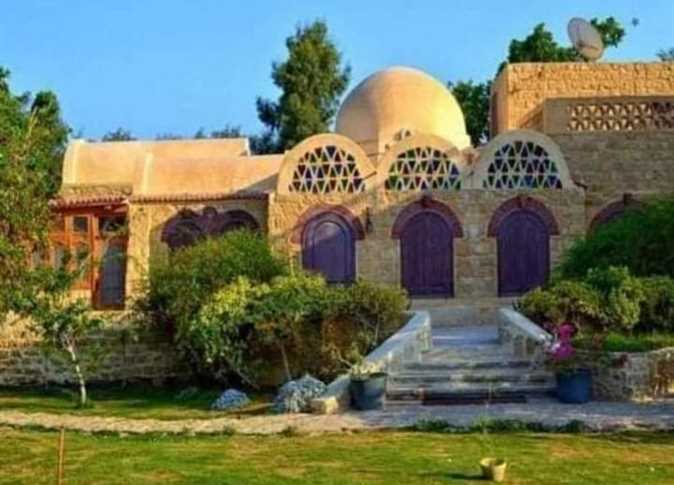

The shift from modern houses with bright and loud colors, American-style open kitchens and practical pieces of furniture, to more classic homes with Middle Eastern designs, complete with arabesque coffee corners and domed architecture, gives a glimpse of hope for a group of people whose livelihoods are on the verge of extinction.

“A new trend towards Oriental Arabic designs and decorations has appeared in newly built homes after the revolution, as it enhanced our youth’s sense of pride and belonging to our great Arabic heritage,” says Engy Bahgat, an interior designer.

“People come to us now asking to design some corners of their homes in the Islamic Arab style. This could be the life line that will save the future of dozens of craftsmen in Egypt who had begun to lose hope,” she explains.

A journey to some of the oldest workshops in Old Cairo is a chance to learn more about the stories and secrets of these forgotten people who have played a big role over the years in preserving an essential part of Islamic and Arabic identity and heritage.

In front of his workshop in Gamaleya, famous for handmade metal handicrafts, you will find Gamal Shosha working a piece of silver.

“The golden age of handicrafts in Egypt has finished; our crafts are dying,” he says bitterly. “I think the main problem is that new generations are affected by American modern lifestyles and forgot their origins and roots, although people in other Arab countries consider copper and silver artifacts a necessity in their houses.

“No one listens to us and no one understands us. It’s not too much to ask. We want to be treated like the other professions. We struggled for more than 20 years to have an association for handicrafts, a union that would enable us to have health insurance and pensions, but the government never listened. The government must help us establish exhibitions and galleries inside and outside Egypt with nominal rents to allow us to promote and market the Arabic heritage represented in our products,” Shosha argues.

“We need support from the mass media to enhance people’s awareness inside and outside Egypt about the historical and aesthetic values of handmade crafts. Simply, we need to feel that we are appreciated by our country,” he adds.

Khaled Mohamed al-Said, an owner of a workshop for carving copper, says no one thinks about Egypt or its heritage. “The revolution filled our hearts with hope and positivity and we started to feel that we finally had fresh air, but now everything is more corrupt than before,” he says.

This is why Said has decided to take a positive step by devoting his time and money to establishing a school for teaching young people handicrafts, especially metalsmithing, in order to bring up new generations that appreciate this art.

“Because the handicrafts became unprofitable, a lot of craftsmen left this career and a lot of workshops were completely closed. This rings alarm bells that require us to be alert to the dangers,” he says.

According to him, one of the two main problems facing coppersmiths is the domination of Chinese counterfeit goods in the local market. Therefore, he thinks that some restrictions must be imposed on these goods regarding their quality and prices, to give Egyptian products a chance to compete with their Far Eastern competitors.

The second issue is high prices for copper. After local copper extraction in Alexandria was prevented, craftsmen were forced to buy imported copper. “Those who were working in gold turned to silver, and those who were working in silver changed to copper, and those who were working in copper began to work with tin. We have to save our crafts from extinction!” he exclaims.

Metalsmithing is not the only handicraft that has suffered over the last few decades. The art of embroidery, which Egypt was famous for since pharaonic times, has also suffered.

Just before the ancient Zewaila gate with its two famous minarets is the tentmaker’s district, known for the embroidery of thick cotton fabric using bright colors. The craft is based either on Arab Islamic arts or pharaonic decoration, but recently natural scenes are being added to fabrics.

“The craft is dying in Egypt and a lot of people advised me to leave it, but I decided to revive it in another place where people will appreciate our skills, civilization and culture more,” says Nasser Abdel Rahman, who moved to Australia. Although he is one of the most well-known embroiderers, Abdel Rahman gave up hope after he found tourists from different nationalities coming to buy his work, only to sell them outside Egypt for thousands of US dollars. “What did Egypt give me to stay here? The officials at the Culture Ministry stole the budgets for establishing exhibitions for our art outside Egypt,” he complains.

Few strong markets for handicrafts exist outside of Cairo. Places like Akhmim, Negada, Siwa, the Delta, Aswan, Shandawil and Shalatin, which are famous for different types of remarkable embroidered clothes, silver, pottery and high-quality carpets exported to Italy, can turn into strong income sources for Egypt if they are exploited and invested in the right way before it’s too late.

“To save these handicrafts, which reflect our heritage and civilization, a group of architects and interior designers have started to visit the places best known for handicrafts all over Egypt, especially in remote areas, in order to create that absent link and connection between craftsmen and the big companies and famous designers. This will help embed the handmade products in decorations inside and outside Egypt as a new trend,” Bahgat, the interior designer, asserts.

Moreover, these designers aim to also help the craftsmen improve their crafts and products in order to be able to compete with their imported counterparts, solve their problems, teach them how to market themselves, help them export their products and increase awareness about the value of Egyptian products. Advocates will present a project to the People’s Assembly about having topics in educational curricula talking about these handicrafts and their historical importance.

One initiative, “Anamel Masreya,” was launched last year by Awtad, a non-profit organization, in cooperation with Mobinil, to provide technical and industrial school students and poor craftsmen with training. It also gives them the necessary materials to start their own small projects and help them manage them as a way to develop more handmade products in Egypt, Sherine Alam, Awtad’s head, has said.

This piece was originally published in Egypt Independent's weekly print edition.