Chapter One: The meeting

Some time during March 2008, I was one of several artists who gathered in the meeting room of Mohsen Shaalan, head of the Fine Arts Sector in the Ministry of Culture. The meeting was one of many that had started a couple of months earlier, with the aim of formulating a new constitution for the International Cairo Biennale, an aging international art event driven to a notorious decline by its previous administration.

Right before the meeting started, Shaalan looked at a multi-page memo covered with signatures and stamps and became furious. He threw the papers on the table, slammed his fists and said, “What else can I do? I have been sending official requests since 2006 to replace the security cameras and fire alarms at the Mahmoud Khalil and the Modern Art museums in Cairo, but to no avail…. Each time I send one to the minister his office responds with either low priority, or no budget, or next year, or your request is being processed.” Though his warnings about the potential dangers of outdated security systems rang hollow at the time, his concerns turned out to be well placed.

Chapter Two: The office

The Ministry of Culture’s organizational chart comprises several directorates named “sectors”. The Fine Arts Sector is one of the principal directorates for several reasons: the minister himself is a painter, as are all the successive sector heads. In true corporate style, the minister oversees the directors of all such sectors–including theater, folks arts and cinema–and delegates different levels of power to each one.

Outside this hierarchy are the Cairo Opera House and Bibliotheca Alexandrina which maintain a good deal of autonomy over their operations. It is a well-known “public secret” (everybody knows it, but nobody talks about) among cultural operators and the Egyptian intelligentsia that there is a “strong man” who exercises management terror over all sector heads: the culture minister’s consultant in charge of public affairs. He determines ministry priorities, what to show and what to hide from the minister. When problems arise, he is the ministry’s problem solver, and sometimes problem eliminator, crushing people and their careers along the way in an overt attempt to save face.

Chapter Three: The Mohamed Mahmoud Khalil villa

The museum of Mohamed Mahmoud Khalil has a story to be told. It used to house its current collection in the early twentieth century, but in 1971 it was converted into an office for former President Anwar Sadat. The estate/palace was equipped with a sealed underground bunker as well as a tunnel crossing the Nile to another presidential residence, to be used only in cases of severe emergency. The annex building complex that now hosts the Horizon One Gallery and the Fine Arts Sector belonged to secret service teams and the presidential guard, whose leader sat in the same office now used by Shaalan. The palace was only handed to the Ministry of Culture in 1993.

Chapter Four: Flashback

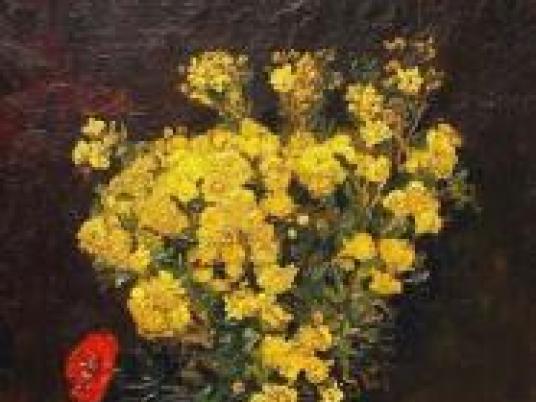

In 1978, a painting from the Mahmoud Khalil collection–kept at the time in a location different from its present one–was stolen. The painting was Van Gogh’s famous Vase with Viscaria (known in the Egyptian mainstream as Zahret al-Kheshkhash, or Poppy Flowers). It was completed in Paris during the summer of 1886 and acquired by Mohammed Mahmoud Khalil Pasha and his wife, Emiline Lock, shortly after. The stolen painting was found in Kuwait two years later, with rumors circulating ever since that what was recovered was actually just a good counterfeit. This allegation was never confirmed nor denied, as the work did not undergo any serious examination.

Chapter Five: August 21, 2010

The very same Vase with Viscaria is stolen again, almost in the same manner: slashed by a cutter blade from the canvas, with the empty frame left dangling on the wall. As an artist and a painter, it saddens me that each time the painting was stolen it lost 3-4 centimeters around the perimeter. A few more times and the canvas will soon be the size of a matchbox.

Chapter Six: Confusion and fury

The catastrophic scenario that Shaalan screamed about at the 2008 meeting has come true. What does he do? The director maintains his calm and follows the set procedures for reporting a burglary: He files a police report, contacts the necessary officials, and calls his boss, the minister of culture. They discuss the issue over the phone and agree on standard operating procedures like two responsible, well-trained and experienced professionals. The minister holds a press conference to announce the loss.

A few hours later, authorities at Cairo International Airport tell Shaalan over the phone that the stolen canvas has been retrieved and two Italian suspects detained as they were leaving the country. Shaalan relays the information to the minister, who in turn announces the good news to the press and, rumor has it, to the president himself. A few more hours later, it is reported that the news may be incorrect due to inaccurate information passing up the chain of command. The embarrassment caused by this blunder proves to be a career killer in the next two days.

Chapter Seven: Laying blame

The “strong man” apparently intervenes to solve the problem. His name appears as the official spokesperson for the ministry. He appears in front of prosecutors, he presents documents and answers questions. Shaalan’s repeated pleas to replace the degenerated security camera and alarm systems in the Mahmoud Khalil and the Modern Art Museums are suddenly forgotten. Responsibility for the theft is dumped solely on Shaalan, who is suspected of negligence and squandering public money. He is unjustly incarcerated for 19 days.

Chapter Eight: Scattered facts

The painting was stolen either on Friday or Saturday. No visual proof exists to identify the exact moment of the burglary. It was a weekend. Saturday is the least busy day for the museum. All the security guards pray together, leaving their unguarded rooms under the supervision of cameras, 37 of which do not work.

Painting thefts from high-security museums happen almost every day, and no one is incarcerated unless there is a direct accusation of burglary. No officials are detained under weak charges of negligence. Nobody is individually accused; stolen works are usually considered a shared responsibility. The detention of a museum director or a deputy minister is unprecedented.

Something is very wrong in this case. Somebody is trying to eliminate the problem, not solve it.

Chapter Nine: “I”

I have decided to serve as a witness for something I saw with my own eyes: Shaalan’s pleas either being neglected, denied or treated as low priority by careless bureaucrats who considered them unworthy of bothering the minister with.

Until a stolen Vase with Viscarias hit the fan.

Khaled Hafez is a Cairo-based visual artist, whose practice comprises painting, installation, video and photography. The photograph is courtesy of Patrick Fabre.