About 15 years ago, Turkey had just launched its first satellite TV station and was able to broadcast around the world. A very popular genre of drama series called “dizi” had been born, and it was appealing to audiences in the Middle East who yearned for something more tangible than the out-of-their-world Mexican, US or Korean soap operas.

A large swath of the 200 million television-owning households in the Middle East warmly embraced the extremely handsome and utterly romantic new Turkish TV idols, who were dubbed into Arabic, carried Arab names and acted out Islam-adherent plots. The costly-to-produce daily episodes of up to two hours dealt with romance, love, arranged marriages, large families, patriarchy and fights against obstacles in the name of justice.

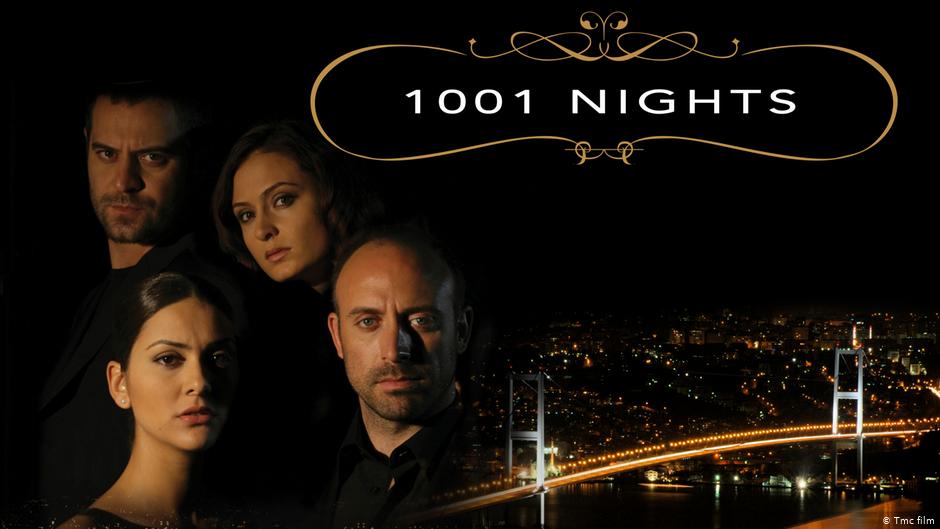

Popular Turkish dizi exports such as Noor, 1001 Nights, Magnificent Century and Resurrection: Ertugrul combine relatable plots, fancy outdoor locations and easily recognizable musical themes. But there is more to it than that.

Firstly, dizis have passed the inspection of the Turkish censorship authority, the Radio and Television Supreme Council, and are thus free of “scenes that are considered obscene and against moral values.” This covers obviously nudity, lovemaking and French-kissing — though fights, violence and guns are considered “safe.”

Secondly, they have not only been dubbed instead of subtitled, but dubbed into Syrian-accented Arabic, which is emotionally more easily accessible than Fusha, the literary and formal Arabic. Fusha, however, had been used for dubbing the previously widely watched Mexican, Korean and US soaps and telenovelas.

Thirdly, Turkish dizis can be easily adapted to and perceived as Arab content. Back in 2007, the biggest broadcaster in the Middle East and North Africa, the Saudi-owned Middle East Broadcasting Center, had bought the Turkish production Gumus, renamed it Noor, and hit its first big success, with up to 92 million viewers following the love story of Mehmet (Mohannad) and Gumus (Noor).

Shortly after followed 1001 Nights, which was sold to almost 80 countries, and Magnificent Century, an epic drama about the life and love of Suleiman the Magnificent. “Magnificent Century has been seen by more than 500 million people worldwide,” Izzet Pinto, the founder of the Istanbul-based Global Agency, which distributes the dizi, told DW. As a consequence, Arab tourism to Istanbul skyrocketed and Turkish soft power started to gain momentum.

‘Anti-Islamic, ‘subversive’ soaps

In April, just before Ramadan 2020, Prime Minister Imran Khan said Pakistan’s state broadcaster, PTV, would screen Resurrection: Ertugrul, dubbed into Urdu. In turn, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s popularity within Pakistan increased. “An Islamist-Turkey has become the role model for Pakistan,” James M. Dorsey, a senior fellow at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies and the Middle East Institute in Singapore, told DW.

Resurrection is the exception at the moment ,as new regulations to protect Pakistani content forbid dubbing. “Now, Turkish dizis are subtitled, and in turn the ratings plummeted,” Pinto said.

Five years ago, the Turkish TV-industry made $80 million a year in the Middle East; in 2020 it was a mere $15 million (€12.2 million). “Before 2018, the Middle East was our best market for export,” Pinto said. “Now there is a nonofficial boycott that led to an 80 percent decrease in revenues.”

Many major buyers have pulled out after the government of Saudi Arabia and the MBC called a halt to the acquisition of Turkish dizis in March 2018, when the Grand Mufti of Saudi Arabia, Sheikh Abdulaziz al-Sheikh, described Noor as “anti-Islamic” and “subversive” and claimed that television channels that broadcast the show are “an enemy of God and his Prophet.”

Another lost market is Egypt, where Turkish TV was banned in 2013 after the military coup against President Mohammed Morsi (who was backed by Erdogan). The support of the Muslim Brotherhood and other Islamist movements still serve as the main argument against Turkey and any broadcasting of Turkish productions.

Dizis go online

Despite the setbacks in Saudi Arabia and Egypt, Turkey’s success at exporting its dizis, and thus its image, continues via distribution platforms such as YouTube, Starzplay, Netflix, MBC and OSN.

And Turkey’s rivals are trying to get in on the trend: Kingdoms of Fire, financed to the tune of $40 million by the governments of Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, debuted in November 2019. The plot takes on Resurrection: Ertugrul by showcasing the Ottomans as “tyrannical occupiers who ravaged the Arab world for centuries,” as MBC describes.

Though the fight between the Mamluk Sultanate of Egypt and the Ottoman Sultan Selim is history, a whole new generation of Saudi filmmakers could take up the battle for influence in the coming years, as Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman has announced a $64 billion investment in the country’s entertainment sector over the next decade.

By Jennifer Holleis