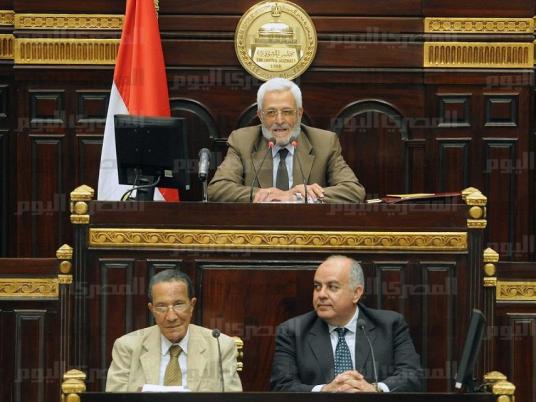

After long hours of article-by-article voting on the Egyptian constitution by the Constituent Assembly, the draft was passed on early Friday.

The current draft has been submitted to President Mohamed Morsy, who in turn will put it up for a referendum, the conditions of which remain unknown in the wake of a recent crisis between the president and the judiciary.

However, the draft follows a tumultuous and unresolved writing process, with many non-Islamist members of the assembly quitting in objection to the non-representative nature of the document. More than 22 members of the 100-strong assembly withdrew, including church representatives, liberal and left-leaning party figures and others.

Several of the articles passed have been a matter of contention. Egypt Independent attempts to identify articles that raised concerns amongst experts in the corresponding fields. On aggregate, the current draft is criticized for not bearing enough safeguards to uphold freedoms, bestows too many authorities upon the president in a way that disrupts the division of powers and generally relies on legal arrangements in critical unresolved matters to evade the lack of consensus over the current draft.

State and society

Article 4 grants Al-Azhar a consultative position after much controversy over the authority it would get in defining the principles of Sharia. The contention pertained to the fact that the principles of Sharia, which according to Article 2, are the main source of legislation, cannot be solely determined by a non-elected body. Al-Azhar’s sheikh is appointed from among the senior scholars of the establishment, and his position is protected from dismissal by the constitution. Meanwhile, the fact that the article on Al-Azhar’s role and its formation remained in the chapter on general principles is still questionable, since it could have been added to the chapter on authorities and establishments.

Article 10 has been contentious, as it gives the state the power to preserve the “genuine nature” of the Egyptian family and its moral values. Article 11 further empowers the state “to safeguard ethics, morality …” The articles give leeway to the state to intervene in private lives, monopolize the meaning of moral values that are naturally dynamic and eventually turn the constitution into a document of identity.

Article 14 limits the stipulation on a maximum national wage by stating that exemptions would be regulated by the law. Economist Ahmad al-Naggar also charges the article with not setting a standard relation between minimum and maximum wage. He also critiques the article for stipulating that wages should be connected to productivity, when productivity is also controlled by such factors like modern equipment, over which a worker should not be held accountable.

Article 15 stipulating social justice in the context of agricultural land ownership is also criticized by Naggar for not setting a ceiling to how much agricultural land can one own. These limitations seem to be glossed over in the midst of a wide belief that the constitution has some favorable allocations for both farmers and workers.

Article 26 is charged with leaving the identity of the taxation system deliberately elusive and not setting up general principles pertaining to the connection of taxes to income.

Rights and freedoms

Article 35 creates an exception to arrest, inspection and detention by the state through a court order to cases of flagrante delicto, the definition of which remains loose. Similarly, an exception to the inviolability of private homes is established for “cases of immediate danger and distress,” the definition of which also remains loose.

Article 43 has been criticized for limiting the state obligation to establish places of worship to divine religions, which exclude other faiths that indeed exist in Egypt such as Bahais. Moreover, Article 44, which prohibits the insulting of prophets, is generally considered a limitation to freedom of expression.

Article 48 has raised concerns over the level of exceptions to the freedom of the media. While it allocates for freedom of expression, it limits it to the confines of principles of state and society, national security and public duties among others things. The spirit of limitations is extended to Article 49, which imposes legal regulation over the establishment of radio stations, television broadcasting and digital media, as opposed to the establishment of printing presses, which only requires notification.

Article 53 limits the representation of trade unions to one union per profession, which counters the ongoing surge in independent unions established in parallel to official ones, which have been criticized for being controlled by the state.

Article 56 does not grant an automatic right for Egyptians abroad to participate in elections, as it is limited by legal regulation.

Article 81 of the chapter on guarantees on freedom and rights limits the definition of freedoms and rights to the principles established in the first section of the constitution titled “the state and society.” As mentioned above, this section is marred with terminology deemed elusive and its articles establish the state’s authority to intervene in private lives on the basis of its responsibility to preserve morality.

General authorities

Article 93 gives the president and the Cabinet the right to demand the secrecy of certain parliamentary sessions, which are otherwise required to be open sessions. While the article says that the assembly decides on whether the demand will be met, it doesn’t specify how this decision will come about, raising fears about executive interference in the legislative branch of government.

Article 104, which explains the dynamics of lawmaking between Parliament and the president, is generally criticized for not empowering Parliament to overturn a presidential veto on laws by limiting the vote on the vetoed law by a two third majority and not a simple one.

Article 105, which allocates for MPs’ rights to address questions and receive answers from the prime minister and Cabinet ministers, does not specify mechanisms and deadlines for the process. Similarly, Article 109, which gives citizens the right to address complaints to the Cabinet through Parliament, also does not specifically outline the process through which they can do so.

Article 114 establishes a minimum number of members for the House of Representatives, but does not establish a maximum number, which is criticized as a possible manipulation by the president’s party. The same criticism, voiced by political analysts with the think tank Democracy Reporting International is leveled at Article 128, pertaining to a minimum number of members in the Shura Council.

Article 139 threatens the House of Representatives within Parliament with dissolution if it fails to approve on the Cabinet platform presented by the president. The president would have to appoint another prime minister from the party with the most representation in the House of Representatives if the first Cabinet’s platform is rejected. In case the second one is rejected as well, the People’s Assembly will choose a prime minister within 30 days; if it fails to do so, it gets dissolved. The threat of dissolution is seen by analysts such as those with Democracy Reporting International as potentially pressuring the house into accepting the Cabinet platform.

Article 171 creates an exception to the openness of court sessions, by stipulating that the court might render a session closed to preserve “morals and public order.”

Article 176 vaguely states that "the law" would govern the appointment of the head and judges of the Supreme Constitutional Court, but also leaves open the possibility of non-judicial authorities appointing them. Similarly, Article 187 leaves governors’ selection to the law, not resolving the question of whether they would be appointed or elected.

Article 197, which establishes the National Defense Council where the military budget is discussed, does not expand upon the process of majority voting that will guide the council’s decisions. This is particularly relevant given the formation of the council, which consists of seven civilian members while the other eight members are from the military, giving it the majority by default.

Article 198 raised eyebrows after extensive campaigning against the trial of civilians before military courts. The article establishes the possibility of trying civilians before military courts if the crime “harms the Armed Forces,” the definition of which is left to the law.

Article 199 empowers the police to preserve public morality, which can potentially conflict with liberties.

Independent authorities and monitoring bodies

Article 202 expands the powers of the president by giving him the power to appoint the heads of independent authorities and monitoring bodies, which is considered executive control.

Article 215 establishes the National Media Council, the responsibilities of which include the preservation of “societal principles and constructive values,” besides its mandate to ensure the freedom of the media. Again, the elusiveness of notions of values and principles raise concerns about how they may possibly act as limitations to freedom of expression.

General principles

Article 219 has raised eyebrows and is widely described as the constitution’s compromise to the long debate over the Sharia stipulations in the constitution. The article specifies the principles of Sharia and its jurisprudential and fundamental basis as being enshrined in Sunni schools of thought (madhabs), adding additional limitations to the rather elusive Article 2, which generally sets Sharia principles as the source of legislation.

Article 231 reverses the previous Supreme Constitutional Court’s ruling on the unconstitutionality of the elections law, which stipulated that two thirds of parliament seats holders are elected through electoral lists, while one third reserved for independent candidates. A similar reversal is also established in Article 232, which reinstates the political isolation law for former regime figures, which was previously reversed by the Supreme Constitutional Court.