On the first day of the doctors’ strike, which had been called for by the general assembly of the Doctors’ Syndicate on 21 September, patients crowded into the waiting room of the Imbaba Fever Hospital.

The hospital is admitting all cases arriving from striking hospitals, even those diagnosed with diseases unrelated to fevers. Yasser Mohamed, 39, is one of those pushed to the facility.

“Doctors are staging a strike at (the nearby) Tahrir Hospital and the Imbaba Public Hospital,” he says. “I had to bring my mother here because she had suffered a surprise stomachache."

Mona Thabet, a pediatrician at the hospital, says they never recognize strikes because their hospital deals with children suffering from dehydration and high fevers, which are emergencies. “The administration, however, told us we are free to choose either to take part in the strike or work, she says. “Had it been in another hospital, I would have gone on a strike because it had been approved by the syndicate, but I cannot shun a patient.”

Meanwhile, Mohamed Salem, a fever consultant and a Muslim Brotherhood member, says cases received by the Fever Hospital are considered emergencies.

“We have to work as normal. Some doctors were confused about the strike but we convinced them that they cannot join,” he explains. “We had expected large numbers of visitors given the strike in surrounding hospitals, so we deployed as many doctors as possible in the emergency and reception departments.”

Mona Mina, board member and a member of the Doctors Without Rights movement, denounced using fever hospitals as an alternative to striking hospitals, adding that such practices should be investigated.

She and others see the use of fever hospitals as a way to weaken the strike and to raise popular resistance through overloads on these hospitals.

Outside the Tahrir Public Hospital in Imbaba, several leaflets calling upon citizens to back the strike are strewn on the ground. The documents stress that the strike aims to ensure the patients’ interests more than those of doctors. Inside the hospital, however, daily activities seem to proceed as usual.

“When we arrived in the morning, we tried to enforce the general assembly’s decision to stage the strike. We informed the ticketing office not to give out tickets to visitors,” says Mohamed Abdel Hamid, a urologist and also a member of Doctors Without Rights. He says the hospital’s director, a Brotherhood sympathizer, threatened the workers with investigation if they refuse to work. According to Abdel Hamid, some elderly doctors yielded to the threats, or attempted to balance their stance, and resume working.

Abdel Hamid says that despite the threat, some doctors insist on striking. “The hospital’s chief does not lend the least attention to the patient’s well-being. He brought doctors [with] irrelevant specializations to check on patients in the striking sectors. He should have told the patients that the specializations they were seeking were not available.”

An ICU nurse at the same hospital says doctors were not sticking to the strike because they feared patients’ reactions.

“The administration ordered the hospital’s clinics to continue to work. They brought physicians with different specializations in place of the striking workers, but there are still clinics committing to the strike,” says the nurse, who preferred to remain anonymous.

Amr al-Nawawy, the head of the hospital, said the hospital continues to work normally, adding that heads of hospitals in Giza had agreed with the governorate’s health department chief to not participate in the strike, due to lack of security at hospitals.

“Strikes should not be made at vital and strategic facilities, such as hospitals. The decision by the syndicate to take part in the strike is not binding, and doctors who refuse to abide by it will not be harmed,” says Nawawy.

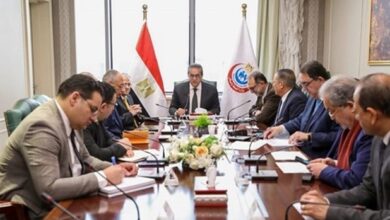

On the first day of the strike, two press conferences were simultaneously held at the Doctors Syndicate. The first was by board members elected and supported by the Muslim Brotherhood, and the second by those elected by the Doctors Without Rights movement. They reflected the divergence over the different blocs’ commitment to the strike, although both groups endorsed it.

Board member Abdallah al-Kariony, a member of the Muslim Brotherhood, said that Article 192 of the Labor Code clearly says that the board of a syndicate is legally entitled to hold strikes.

He also said that it was the young members of the syndicate who called for the general assembly that endorsed the strike, and that a statement was issued two weeks before the assembly meeting, in which the majority of the elected board suggested to adopt the strike.

“Anyone claiming otherwise would be a liar,” asserts Kariony. “Though we are keen on the success of the doctors, we must adhere to the law.” He says that Doctors Without Rights movement welcome efforts to strengthen the strike.

Meanwhile, Mina said that the general assembly chose a committee to manage the strike, and that the matter was not left for the board to decide, as the majority of its members were against it.

“Naturally, only those who are for the strike should manage it,” says Mina. She called on the media not to focus on differences, but rather on the crux of the matter, which is the doctors’ demands for better hospitals, salaries and a raise in the Health Ministry’s share of the state budget from 4.5 percent to 15 percent.

According to Mina it does not make sense to suspend the strike lest hospitals are attacked, when ensuring the security of hospitals is itself one of the demands of the strikers, who hold the Health Ministry responsible for protecting striking doctors.

Board member Ahmed Lotfy, a member of the Muslim Brotherhood, said that doctors who are not participating in the strike are not necessarily of a different political inclination, but rather unconvinced of the idea.

“Some believe that an assembly of 1,000 doctors has imposed its views on 250,000 other doctors,” says Lotfy, who denied that the strike has anything to do with politics.

Seventy percent of doctors have participated in the strike, except some in Giza, the Red Sea and North Sinai, he says. “This is why we authorized the local branches of the syndicate to handle the matter themselves, without compromising the safety of the doctors and the patients.”

He also notes that only another assembly could end the strike. “We will see what we will do once the government meets our demands.”