On Thursday afternoon, artists continued to flock to the Palace of the Arts at the Opera House grounds, eager to know whether their works had been accepted in the 22nd Youth Salon, scheduled to open tonight, showcasing the work of 252 artists. A man in his late 20s with a dark complexion and dressed in a hooded sweatshirt came all the way from his town in Upper Egypt and left disappointed.

A young mother of two, who I will call Nora, described her submitted artwork as “a large painting of a girl seated in a flowing red dress.” She tucked her two children along as she went to the palace. “I don't want to wander the galleries on the opening night, looking for my work to know if it was accepted," she explained.

The great anticipation and possible frustration are equally common feelings surrounding the annual mega exhibition, designed to scout for new artistic talents and explore the trends and themes young artists are engaging with.

When Nora came in, the salon’s commissioner, Khaled Hafez, was adding his final touches to the exhibition, tweaking the display after the selection jury added some 40 works to the salon while he was in Mali receiving a prize for his “Aha Project” video work from the African Biennale of Photography. Hafez had only worked on the exhibition for a few weeks, from deciding on the selection with the jury, to redesigning the maze-like galleries of the Palace of the Arts to host the works. Several walls were painted in bright red and blue in contrast with the artwork, and the architectural niches of the building were used to host sculptures, installations and even artist performances scheduled for the opening night.

Trying to comfort Nora, Hafez told her that he would have someone check the lists for her name, “but you must not be upset either way.”

"Whether I’m upset about the selection or not is something I cannot control,” she responded. And indeed her teary eyes upon hearing the rejection of her work reflected how much the Youth Salon means to local artists. Despite Hafez's attempts to comfort her, Nora walked away, seeming helpless rather than convinced.

Since the salon’s establishment in 1989 under the auspices of the then newly appointed Culture Minister Farouk Hosni — Hosni served in that position for 24 years before he was removed from power in the January cabinet reshuffle — it has been seen as an excellent platform to launch artists' careers.

Some of the most established Egyptian artists now exhibited at the salon early on in their careers. Amal Kenawy, who won the grand prize in the 12th Cairo Biennale last December for her installation/performance work “Silence of the Sheep,” exhibited publicly for the first time in the 1997 Youth Salon, and received the first prize. Acclaimed visual artist Wael Shawky, who won the 2012 Abraaj Capital Art Prize last month, participated in several editions of the salon in the 1990s before he won the grand prize in 1994 for a mixed media installation piece. And among the younger artists, the names are many, from Magdi Mostafa and Mohamed Allam to Islam Hassan, who won the salon’s prize for printmaking in 2010.

But despite the rising stars of some of the salon’s artists, its role has been widely contested, and the decisions of the selection and awards juries repeatedly criticized. Notions of putting together a curated exhibit were often confused with those of representing the scene and at times providing exhibition opportunities art-fair style.

Several members of the Asala (authenticity) artistic movement promoting an Egyptian identity as a defining criterion of Egyptian art accused the salon of promoting western artistic forms and themes. Others argued that “contemporary” forms were not represented enough; all this while the “young” artists mostly complained about issues of in/exclusion or the lack of clear selection criteria to the average 300 works selected for exhibition.

In 2009, the selection jury was severely criticized for accepting only 101 out of 1293 submissions. Visual artist Hassan Khan, who was on the jury, explained in an interview with Al-Masry Al-Youm that the main defining criterion should be the strength of the artworks and how they fit within the overall exhibit instead of “a vague official consensus.”

“The salon [historically] played a role in the general intellectual corruption of the time. It was a political tool … to bribe young people … Young artists would make submissions and the state, represented through the Ministry of Culture, would exhibit them. That way, everyone could feel good about themselves. It’s all part of a facade whose sum total is to actually weaken the art scene,” Khan explained.

At the opposite end of the spectrum, the selection jury appointed in early 2011 decided to accept and exhibit all submissions. Reda Abdel Rahman, the commissioner of the salon before being replaced by Hafez, described this decision as a “democratic one, celebrating young Egyptian artists,” one that is inspired by the values of the 25 January revolution. After much public debate, Minister of Culture Emad Abu Ghazi annulled the jury’s decision for being illegal and a new jury and commissioner were selected. Critics of Abdel Rahman’s decision described his act as “corrupt’ echoing the views mentioned previously by Khan.

Two months down the line, the salon is opening under the broad theme of “change” — inspired by the continuous fervor to celebrate the ongoing revolution.

How much the selection criteria has changed is debatable. But, Hafez expects this year’s edition to be “one of the strongest salons yet.” He admits though having complied to some internal politics in the selection process, at times “compromising the quality of selected artworks when there are compensatory elements in terms of technique.” The state-funded salon is perceived as the main support structure for young artists and as such some believe a significant proportion of the submissions should be exhibited; 252 out of 1200 submissions have been accepted this year.

Hafez’s vision for this year’s salon is to work between good craftsmanship and scouting for fresh ideas, if any. “I look for artists who are technically proficient and who show potential of producing strong work in 5 to 10 years,” he explains. He quickly dismisses the word “concept” as a defining factor in his selection, arguing that it is commonly abused to promote “half talented artists.”

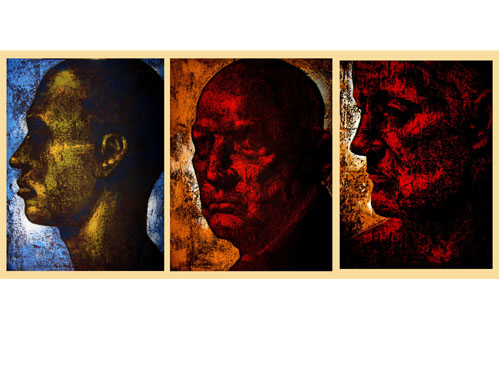

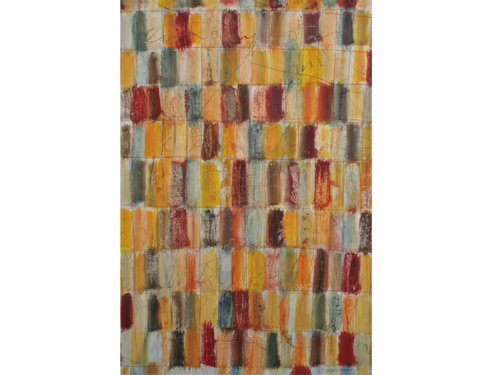

The majority of the works are exhibited at the Palace of the Arts thematically. Hafez is particularly interested in exploring artists’ obsessions reflected in their work, and this was his guiding curatorial paradigm. Some artists seem obsessed with notions of identity. Struggle for power is another prominent theme at the salon, to which a whole gallery is devoted.

As much as he hopes that the salon will offer visitors a bird’s-eye view into the practices of young artists, he is wary that many of the works are produced with an eye on the salon, at times tailored toward whatever perceptions artists have of the selection criteria, so do not always reflect “authentic” studio practices.

Inevitably, much of the works in the various galleries draws on the theme of the revolution. Some were clearly presented in that context such as photographs taken during the 18-day protests hung along the walls of a corridor and contrasted with less representational works on the opposite wall. Others are scattered in the various galleries, at times fitting with other curatorial themes.

Despite the challenges, curating an exhibition of young artists is a fun process. “One is always up for a potential surprise,” says Hafez, and in a few years time, many of these artists will be established.

One tradition of the salon aimed at supporting artists is monetary prizes, a tradition that Hafez and other artists wish to replace with residency programs. Hafez himself has just won a two-week residency in France from the African Photography Biennale.

“It is such initiatives that have a true and lasting effect on the practice of artists and their development. It did not happen this year, but is among the recommendations I made to the salon’s organizing committee, so maybe next year," he said.