There are fears for the life of the last Egyptian detained in the US Guantanamo Bay facility. His health appears to be deteriorating, even as developments in his legal case provide hope that he may one day be released.

Authorities are refusing specialist medical treatment, or even to allow his lawyer to view his medical records.

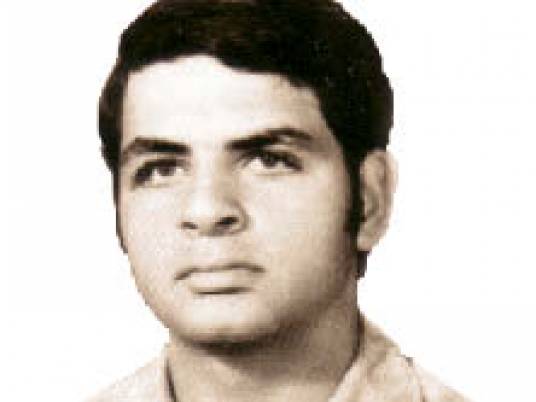

Tariq al-Sawah, born in Alexandria in 1957, is not charged with any crime. A previous Egypt Independent investigation told Sawah’s story and pointed to the errors and inconsistencies in leaked US government documents recording allegations against him.

Sawah was volunteering in a refugee camp for Bosnians fleeing Serb ethnic cleansing in 1992 when he became involved with a Mujahideen Brigade fighting for the Bosnian cause. When the war ended, he settled in Bosnia, married and had a daughter.

However, he was forced to leave the country due to the terms of the Dayton Peace Accords, which ended the war in Bosnia. Refused entry to a number of other countries, he finally arrived in Afghanistan.

Sawah says the Taliban drew him into fighting against the Northern Alliance — a fight that he was persuaded was equivalent to those in Bosnia. Although this put him in contact with associates of Al-Qaeda, there is no evidence that Sawah himself was a member or that he was ever involved in either terrorism or fighting against NATO coalition forces. There has been no evidence provided to contradict Sawah’s account, including in the leaked US files.

During his captivity, military officials have reportedly described Sawah as broadly cooperative and forthcoming when questioned. His military-appointed lawyer, Lieutenant Colonel Sean Gleason, has said three former Guantanamo commanders have provided letters indicating that he “is not a threat and recommending he should be released.”

When Gleason pressed in August 2011 for Sawah to appear in court to prove he is not guilty, the government responded by withdrawing the two formal charges then leveled against him.

What is more, those two charges no longer exist in law. In October 2012, the Federal Court of Appeals in Washington overturned the military commission conviction of former Guantanamo detainee Salim Hamdan on the basis that the charge of “providing material support for terrorism” is not a valid criminal offense.

Then, on 25 January of this year, the same court overturned the military commission conviction of Guantanamo detainee Ali al-Bahlul, thereby eliminating “conspiring to provide material support for terrorism” in the same manner.

In March 2011, US President Barack Obama issued an executive order requiring that Guantanamo’s remaining detainees should receive Periodic Review Board hearings to determine their eligibility for release. The board cannot actually release people, but makes recommendations based on the potential danger the detainee represents to the US.

Obama’s order also provided a legal framework for continued detentions at Guantanamo Bay, negating a 2009 presidential promise that the facility would be closed.

To date, no such hearings have occurred — a fact for which no official explanation has been provided.

In August last year, President Mohamed Morsy formally requested that Sawah be released and repatriated. The Egyptian government has hired a lawyer, Robert Tucker, to formally request a hearing for the detainee.

Tucker was retained in December, but was unable to start work until funding was released to him on 25 January.

Sawah’s case has also been subject to legal proceedings since 2005 under the principle of habeus corpus. This requires that a person has the right to appear in court, be judged and released if found not guilty.

A Washington district court denied a request that Sawah be freed on an interim basis, pending a Periodic Review Board hearing, in November.

At risk of death

While in captivity, Sawah’s weight has more than doubled, leaving him morbidly obese. Beset with respiratory and heart complications, he is “at significant risk” of death, according to a doctor. Authorities have refused him appropriate treatment, according to his doctor and lawyers, and continue to withhold his medical records.

Dr. Sondra Crosby, an associate professor of medicine at the Boston University School of Medicine and Public Health, has examined Sawah twice. In an October letter addressed to one of Sawah’s lawyers, Crosby wrote that his “extreme obesity” has left him at “an increased risk of death from all causes.”

With a body mass index of more than 40, Sawah is so obese that he cannot sleep lying down, lest the soft tissue from his neck block his airway. He is at great risk of coronary artery disease and heart failure, and his “functional status is extremely limited.” Associated with these conditions, and with his long internment, he is described as depressed and hopeless, with impaired neurocognitive functionality.

To Crosby’s knowledge, Sawah has not received appropriate specialized evaluation or treatment for his condition. The doctor’s letter was provided to officials at Guantanamo and filed in a federal court in October.

Gleason’s request for a specialist physician to develop a treatment plan for his client has been ignored by the military commander at Guantanamo, he says, and he is unaware of any steps being taken to treat his client’s “life-threatening heath concerns.”

Gleason has been told that Guantanamo detainees are fed the same food as the guard force, leading him to believe Sawah’s weight problem is underpinned by other factors.

Backed by his client, Gleason submitted a request for Sawah’s medical file in August 2011. The US government has classified detainee medical records at Guantanamo as secret, but although Gleason has the appropriate security clearance, he has not been allowed to view the records. He says he has received no official explanation.

However, it appears that during his internment, Sawah was fed unhealthily at times to encourage compliance. Citing a former military official, the Washington Post reported in 2010 that “the overweight Egyptian was enticed with takeout from the Subway franchise on the base.”

In his book “The Black Banners,” former FBI interrogator Ali Soufan wrote that he questioned Sawah in 2004, describing the detainee as “overweight and happiest when we’d bring him ice cream.”

There have been no further independent medical examinations, but Gleason and Sawah’s family say they have reason to believe his condition is worsening.

“It is clear to me that Sawah’s health has been declining over the 18 months I’ve been seeing him,” the lawyer said in an email interview. “It doesn’t appear that his weight has increased or decreased during the time I’ve been meeting with him, but his energy levels have been steadily declining.”

He said Sawah is also experiencing memory loss.

Sawah’s daughter and one of his sisters spoke to him via Skype early last month from Alexandria and, his brother Jamal says, his sister had the impression that he is in a worse condition than on any of the previous occasions on which she has spoken to him in captivity.

In September last year, there was talk of sending an Egyptian government delegation to Guantanamo to evaluate Sawah’s health, Gleason says. This visit has yet to occur.

Bosnia connection

Last month, Columbia University anthropologist Darryl Li interviewed a Bosnian man who fought alongside Sawah in the Mujahideen Brigade.

Li agreed to put a question to the Bosnian source on behalf of Egypt Independent.

“He had a big body, big hands, big hair. He looked dangerous, but was actually a very good person,” the source recalled. “He didn’t get into discussions much, was quiet. He found himself in jihad because it was a simple challenge. [He] used to say, ‘You should be patient until the action.’”

He said Sawah avoided factional associations within the brigade.

“I’m absolutely sure that he’s not a guy who should be in Guantanamo… Maybe he’s a dangerous-looking guy [… but] he wants to do some practical good in the world,” the man told Li.

Sawah’s involvement in the brigade is not part of the case against him. Although it is commonplace to think of “mujahideen” and the US as being firmly at loggerheads, this was not always the case in Bosnia.

Despite the United Nations’ arms embargo that it was supposed to be enforcing, the US turned a blind eye to Iran’s arming of the Bosnian forces, including the mujahideen. The US may even have provided some of the transport planes — black Hercules C-130s.

The Bosnian last saw Sawah at Sarajevo airport as he left the country for the last time. He was unable to return to Egypt for fear of persecution under former President Hosni Mubarak.

More than a decade and a revolution later, his family still waits to welcome him home to Alexandria.

“[Sawah] has now been held by the United States for over 11 years without being tried or convicted of any crime,” said Gleason. “He looks forward to having an opportunity to clear his name and to be reunited with his family in Egypt. Based on his declining health condition, he hopes that day comes soon.”

This piece was originally published in Egypt Independent's weekly print edition