Located on the ground floor of a spacious low-rise building, shaded by tall trees facing a small garden, the Greek Club in Alexandria’s Ibrahimeya neighborhood has been a social space for Greek residents, expatriates and many Egyptians since it was founded in the early 1920s.

Photos of the interior today show worn out wooden chairs stacked against striped blue walls and cardboard boxes full of newspaper-covered cutlery in its abandoned corners.

Any day now, the Greek Club in Ibrahimeya will be demolished to make way for an ambitious shopping mall. Last week a public affairs TV show brought attention to the club’s impending destruction and a small group protested against it, but it seems this will not be enough to halt the tractors and cranes.

Mohamed Adel Dessouki, an architect and member of the Alexandrian Architectural Heritage Conservation Committee, said that although the building housing the Greek Club is not of unique architectural value, its function as a public social space for decades has resonated with many Alexandrians of different ages eager to preserve their past.

While the demolition of old buildings for the sake of large real estate developments has been ongoing for many years now in Alexandria, there has been a noticeable increase since the 2011 revolution. In the increasing absence of police presence on the streets, contractors have resorted to sabotaging old buildings in perfect condition to make them eligible for demolition and sale, architecture and preservation scholars say.

“When it’s a question of population density versus architectural heritage, you know who will win,” says Mohamed Amin, a filmmaker making a documentary on Alexandria’s heritage sites. Amin’s name has been changed for the purposes of this article because he fears the real estate companies will interfere with his work if he speaks publicly about them. “All of Alexandria is for sale, especially the old buildings in densely populated areas where real estate is expensive.”

The Greek Club is not the most significant building to be targeted in the most recent round of demolitions, but the public interest in its case is helping shed light on the destruction of more important structures.

Alexandria has lost many architectural gems and valuable heritage sites in recent years, including the Count Zogheeb Palace in Raml, Prince Tooson’s Palace near the Antoniadis Gardens, and Bayram El Tonsi’s house in Anfoushi. Following decades of neglect, squatters and attempts to demolish it, the villa of celebrated novelist Laurence Durrell in Moharam Beh is a sad example of how ineffective the heritage law is at protecting buildings.

Dessouki cites the Gustav Aghion Villa in Wabor al-Maya, the Sidnawy villa in Moharem Beh and the Asia Dagher villa in Glym as important heritage buildings that were sabotaged to make way for real estate developments.

The Cicurel residential villa in Roushdi is another example of widespread corruption in the Egyptian real estate market.

Built in the 1920s by French architects Leon Azema, Jacques Hardy and Max Edrei, the art deco villa in Roushdi was the residence of Joseph Cicurel, the Jewish-Italian owner of the Cicurel department stores. The building was nationalized in the 1960s and is now owned by the Arab Marine Navigation Company. It is listed as a heritage site and protected by a 2006 law that prohibits modifications without notifying the architectural heritage committee.

In January 2012, Prime Minister Kamal Ganzouri decided to remove the Cicurel building from the heritage site list, thus making it eligible for sale and demolition. The government’s illegal intervention in the building’s fate shocked Dessouki and his committee members.

“It is simply not their legal right to remove the building off the list,” Dessouki says. “The legal system is constantly being manipulated when it comes to contractors seeking to destroy these heritage buildings.”

Mohamed al-Shahed, a writer and scholar specializing in urban issues in Egypt, says that such issues should be handled by the municipality, rather than the prime minister himself, and called the removal of the Cicurel’s protected status a “clear example of a public and obvious display of corruption” In favor of the contractors and potential new owners.

Shahed equally blames the heritage protection law for being easily manipulated and for doing little to preserve a site’s property value.

“It’s either insignificant or it tailors to benefit the contractors,” he says. “It’s pointless to put these villas on a heritage list that doesn’t protect them or preserve their value. It just creates dead spaces.”

Shahed insists that the whole heritage issues fits within a much larger context of a completely unregulated real estate market.

“There is an urgent need for a package of laws and regulations that work together in the real estate market,” he says. “There are a lot of heritage places that are rotting. The laws should ensure saving these sites by maintaining their value, not just protecting them from demolition.”

The loophole in the heritage law has been systematically exploited as contractors intentionally sabotage heritage buildings.

“The contractors go on hunting sprees for potential money-making properties,” says Shahed. “And they operate more blatantly in Alexandria than anywhere else I’ve seen.”

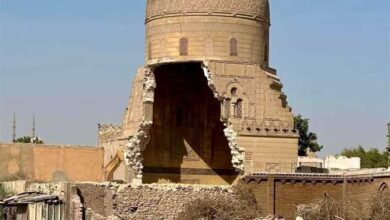

“This mafia works exceptionally well in Alexandria,” Amin says of the real estate developers. “They will ram bulldozers into the walls of buildings or by flood the foundations with water to destabilize the structure, thus making them eligible for demolition.”

A perfect example is the Asia Dagher villa on the Glym tram tracks. Dagher was a Lebanese filmmaker who made some of Egypt’s most celebrated films in the 1930s, including “Rodd Qalbi” and “Al-Nasser Salah Eldin.” She was the aunt of Egyptian filmmaker Youssef Chahine.

Shahed says her history and value to Egyptian cinema makes the villa an obvious choice for a museum, but it was recently sabotaged by contractors who hammered into a corner of the building until it partially collapsed and flooded the foundations with water. Neighbors claim that the family lawyer was involved in this scheme to sell the property, which was previously in perfect condition.

Shahed speculates that few remember Dagher today, and notes that hers is a good example of why the definition of heritage sites needs to be changed.

“Official heritage dominates our conscience,” he says. “So a palace or a large mosque is accepted as heritage, but these buildings like Asia Dagher’s and the Greek Club are heritage too. The old streets, the neighborhoods and these homes are all documents telling us the history of their inhabitants, of the society then. They tell us the real history, the people’s history.”

With little left of Alexandria’s rich architectural history of the past 100 years, the Greek Club’s demolition is yet another sad end to the former urban landscape of the city. The tree-lined neighborhood of Ibrahimeya on the tram tracks has changed drastically in recent years. Today, barely three or four old buildings survive on a 5 km route, amid empty lots of land, new structures and closed up buildings that look ready to be pulled down at any minute.

Until progress is made in rehabilitating the laws governing real estate in Egypt and specifically protecting and preserving valuable heritage sites, young Alexandrians like Amin are left with no recourse but to film and archive these nostalgic spaces for memory’s sake.

“Given the ignorance that we live in, it won’t be a surprise if [celebrated poet P.C.] Cavafi's house or Laurence Durrell’s house are pulled down soon,” he says.