The Dead Sea Scrolls were fated to a controversial place in history. After being secreted away in a cave, supposedly by an ancient monastic Jewish community, they lay hidden for nearly 2000 years until being discovered in 1947 — just the right moment to become entwined with the deeper conflict of who would claim which pieces of the Holy Land.

The seven primary scrolls found in the first cave at Qumran, near the Dead Sea, eventually made their way to The Hebrew University at around the same time Israel became a nation. The Israeli government took another large collection, discovered in later excavations, from Jordanian custody and placed it in the Rockefeller Museum in East Jerusalem as spoils of the Six Day War in 1967.

Important to contemporary understandings of the history of Judaism and the birth of Christianity, and often called the “most important archaeological discovery of the 20th century,” the scrolls have weathered years of controversy over access and ownership. Now with a little help from Google, the Israel Museum has made five of the most complete scrolls freely accessible to anyone, anywhere in the world, complete with commentary and English translations, via the internet, with more complete digitization of the collection in the works.

The scholarly value of this recent development is a subject of debate, and the availability of the scrolls online is unlikely to settle longstanding ownership disputes with Jordan and Palestine. But the scrolls have always carried as much symbolic as scholarly import, and this latest development is no different. The history of the Dead Sea Scrolls runs consistently parallel to the progression of access to information with changing technology over the past several decades.

Around the time Israel took possession of Jordan’s scrolls, a scholarly storm began to brew around the slow pace of published translations and facsimiles. In 1977, Oxford professor and leading Dead Sea Scrolls scholar Geza Vermes claimed the continued refusal to publish the documents would become “the academic scandal par excellence of the 20th century,” according to the Biblical Archaeology Review. The controversy over incomplete access and reproduction continued to build until 1991, when a pair of biblical scholars from Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati, Ohio put together a pirated version of the scrolls and made a renegade publication.

“This is an attempt to break their monopoly,” professor Ben Zion Wacholder told The Chronicle of Higher Education, speaking of the small group of editors responsible for the transcription and publication of the documents.

Displaying impressive cyber ingenuity, Wacholder and his colleague Martin G. Abegg put together an approximation of the unpublished scrolls by designing a computer program that would reconstruct the manuscripts from a concordance — an alphabetical catalogue of every important word in a document — that was published in the 1950s.

This act of information liberation, followed by an unauthorized publication of photographs of the scrolls by the Biblical Archaeology Society, forced official loosening of control of the manuscripts. In early 1992, the Israeli Antiquities Authority officially allowed scholars who research the scrolls to publish critical editions including photographs of the documents they saw for the first time, and around the same time approved the creation of a microfiche facsimile in the Netherlands, officially allowing access to the documents to scholars across the world.

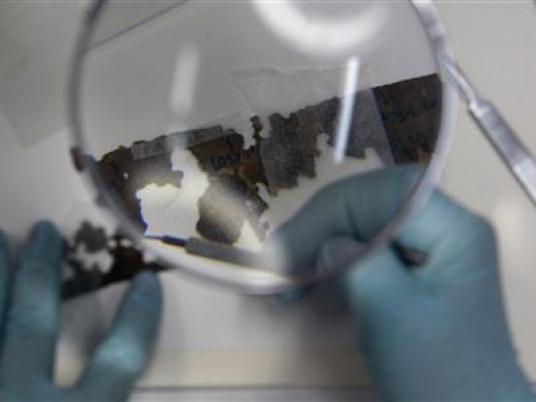

But the digitization of the scrolls by the Israeli Antiquities Authority and Google marks the pinnacle of open access, though completing the process of digitization will take years. Documents once preserved in a cavernous hideaway, and then held for decades under tight control by a small number of scholars, can now be examined with the tap of a track pad.

But in the years intervening between loosening control of the documents and their current digital liberation, numerous reproductions and translations have been published, and this landmark for public access has been greeted by scholars with a degree of apathy.

Youssef Zeidan, director of the Manuscript Center and Museum at the Bibliotheca Alexandrina, feels that the digital facsimiles, despite claims of excellent clarity and magnification capabilities, are not tools for scholarly research.

“I cannot say something serious or real about these pictures. They are just pictures,” says Zeidan.

Zeidan lamented the fragmented nature of the Dead Sea Scrolls collection, parts of which are spread out in museums across the world.

“When the scrolls were first discovered, Israeli institutions took some of them, some went to Europe and other places, and now we just have some copies,” he explains. “We cannot study these scrolls in the correct way because they are not complete.”

Mohamed Hawary, Professor of Jewish Religious Thought and Comparative Religions at Ain Shams University echoed Zeidan’s sentiments, saying “I advise scholars, if they want to study manuscripts to examine the original.”

Nonetheless, Hawary suggests that the digitization of the scrolls may encourage scholarship in general, and particularly among Arab scholars, for whom it is difficult to travel to Israel, or even to Europe or the United States.

“The fact that they are available will be helpful for scholars because now if I want to start to study documents from the Dead Sea Scrolls I can study them online, instead of living in Israel or going to Israel.”

Still, according to both Zeidan and Hawary, no scholar can publish anything that will be taken seriously without examining the actual documents.

“I could study the documents online, but before I finish or publish anything I would go for two nights to see the original,” notes Hawary.

And the fact remains that the community of scholars with the knowledge necessary to interpret the scrolls is very small. Michael Reimer, professor of History at the American University in Cairo, suggested the importance of the digitization of the scrolls has been overblown for precisely this reason.

“I do not think the fact that they are now available online makes very much difference because you have to have very specialized knowledge to read these things,” says Reimer.

It may be characteristic of scholars who deal so exclusively in the disintegrating fragments of ancient times to be dismissive of advances in technology. But the general accessibility of the scrolls may have consequences no one can foresee.

“Maybe a new generation of scholars will come around and look at this with a methodology that we do not even have now,” says Reimer.

A sign that Reimer may be right, a feature on the Cloudline Blog at Wiredmagazine, suggested the dawning of a new age of wiki-scholarship: “The second phase [after digitization] is to offer some kind of open mechanism for letting scholars … attach metadata and conversation to the different layers (raw image, color-corrected image, multi-spectral image, transliteration, transcription) of the online text.”

While the scholarly community may maintain ambivalence toward the latest sensational development in a history that has been sensationalized at every turn, the digitization of the Dead Sea Scrolls nonetheless can be seen as symbolic of our new age of information freedom, and the strength of the growing tide toward open access for all.