More than elsewhere, the coronavirus outbreak has put Saudi Arabia’s vision for the future in jeopardy. The collapse in oil revenues and the rising influence of the religious establishment could derail its plans.

Saudi Arabia is currently scrambling to contain two major threats: Coronavirus infection rates have shot up sharply recently, while at the same time its huge oil revenues look set to shrink as global prices plunge, throwing the country’s plans for the future in doubt.

In mid-April, together with OPEC, Russia and other oil producing states, the kingdom agreed to an unprecedented cut in oil production to stave off falling prices due to a massive 30 percent drop in global demand. The bloc, known as OPEC+, promised to reduce output by 10 percent of world production.

But oil producers are still having trouble selling the oil they already have, sending prices into a nosedive. On Monday, the price for West Texas Intermediate, the benchmark variety of crude, briefly fell into negative territory as full global storage facilities left nowhere for producers to send their product.

Rapidly rising infection rates

The oil crisis comes at a time when Saudi infection rates for the new coronavirus have risen sharply and the royal family is in retreat.

Confirmed cases of the virus almost doubled between April 17 and April 22, according to figures from Johns Hopkins University. The country registered 12,772 cases by Wednesday, up from 7,142 the previous Friday, and 114 deaths. The kingdom’s roughly nine million foreign workers are also seen as a possible vector for the virus. Many have been stood down without pay and live in poor accommodation or labor camps where infections are rising and social distancing is near impossible.

Up to 150 of the country’s positive cases are members of the royal family, according to a report in the New York Times, providing perhaps one of the motives behind the scale and speed with which the kingdom introduced restrictions early on. King Salman and de facto ruler Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, are reported to have secluded themselves in separate retreats on the Red Sea, along with many of the government’s ministers.

‘Vision 2030’ at risk

While the Crown Prince is in lockdown, his ambitious political and cultural agenda has come into question. Dubbed “Vision 2030,” it is intended to prepare the kingdom for the time when oil revenues will not flow so generously.

In February, the International Monetary Fund said that Saudi Arabia and other Gulf states’ wealth could run out in the next 15 years to 20 years.

In the short term, the falling oil price combined with the corona epidemic is a bitter setback for “Vision 2030,” said Stephan Roll, head of the Middle East and Africa research group at the Berlin-based German Institute for International and Security Affairs (SWP).

Aside from lower revenues, the planned second release of shares in Saudi Aramco, Saudi Arabia’s state oil company, will also become unrealistic under the current conditions, Roll said. “A further sale of Aramco shares would have made money available for major projects. Added to that, the Hajj will be cancelled — another important source of income for the kingdom.”

A return of the Wahhabis?

A second major element of “Vision 2030” had been to moderate the ultra-conservative Sunni state religion, in part to woo Western countries, where the image of a modern cosmopolitan state is important in political and cultural relations.

For a long time, the Wahhabi clergy’s power was based on a pact with the royal house: The House of Saud retained political power while securing considerable influence for the Wahhabis. At the same time, religious scholars used that influence to give religious legitimacy to the Saud family’s rule.

The clergy also gained influence and attempted to distract the population from questions of politics by bombarding them with fatwas that focused daily attention on religious life, according to Madawi al-Rasheed, a Saudi anthropologist and author of “Contesting the Saudi State.”

More recently, Mohammed bin Salman had pushed back on the clergy’s sway, but now the pandemic seems to have given Wahhabi theologians a new lease on life.

For example, at a moment when important messages to quell public concerns and spread strategic public health information might have come from government, the royal family has given license to clerics to disseminate advice on the new coronavirus in government-produced videos.

In one, a religious scholar demonstrated how to use disinfectant properly. In another, the audience learned that when the Prophet Muhammad sneezed, he held either a hand or cloth in front of his face.

All told, the dual challenge of falling oil revenues and the coronavirus pandemic pose a political and economic risk for the kingdom, mainly because of the way it is governed, Stephan Roll said.

“There is a lot of unpredictability there. There is a tendency for ad hoc decisions. Those at the center of power are impulsive and uncontrolled. All of this could mean that the country may emerge from the crisis economically weakened.”

___

By Kersten Knipp, Ismail Azzam

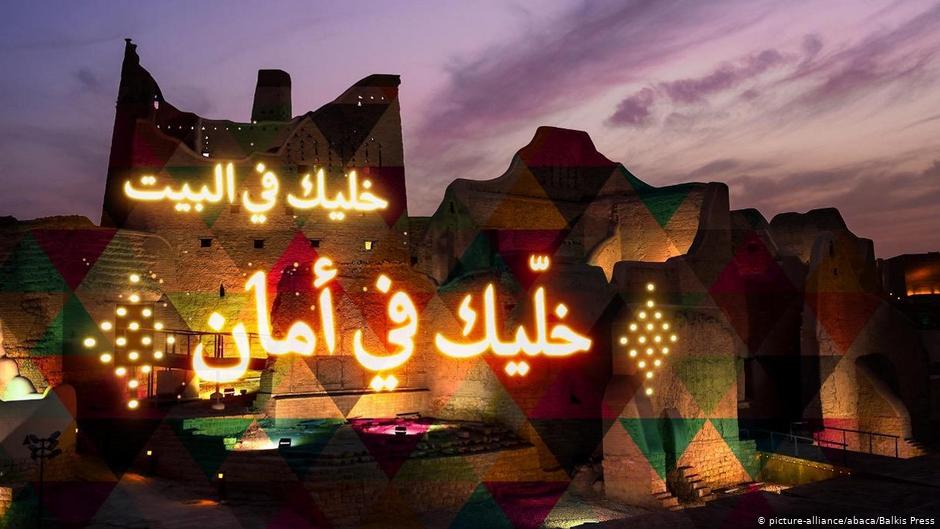

Image: Stay home, stay safe! A wall projection in Riyadh. (@picture-alliance/abaca/Balkis Press)