“The idea of travelling has controlled their minds…People who travelled started building concrete houses and multi-story buildings. The youth became jealous of each other…and travelling became the dream.”

The father of a young Egyptian man who took to the sea to reach Italian shores recounts his version of what has become the story of many others like his son.

Thousands of Egyptians have migrated to Italy in the past 20 years, making it the first destination for Egyptian migration to Europe. Nevertheless, European laws on migration are very restrictive, thus it is very difficult for Egyptians to travel legally.

More than hundreds of thousands of Egyptians now reside in the city of Milan, and a new generation of Italian-Egyptians is becoming an important part of northern Italy’s society.

While some may think migration via the Mediterranean Sea is a somewhat new phenomenon, the ties between the Italian and Egyptian people dates back to millennia ago, when the two countries were still known as the Roman Empire and the Land of the Pharaohs.

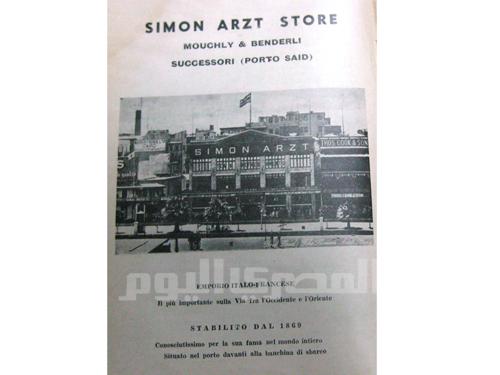

Ever since the Kingdom of Italy was formed and long before the Arab Republic of Egypt was born, the two countries relied on a solid collaboration in a myriad of different fields, from art to commerce, technology, infrastructure, artisanship and, later, the automobile industry.

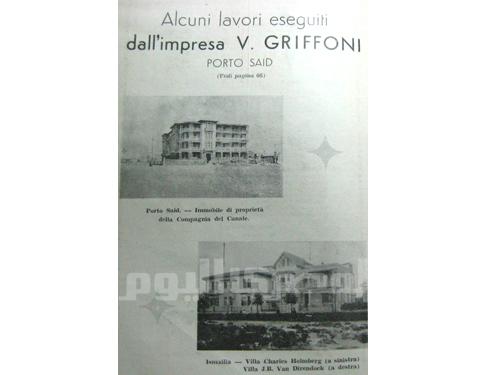

Italians contributed significantly to Egypt’s “modernization” process as Egyptian rulers were aware of their famous skills in architecture, engineering and art.

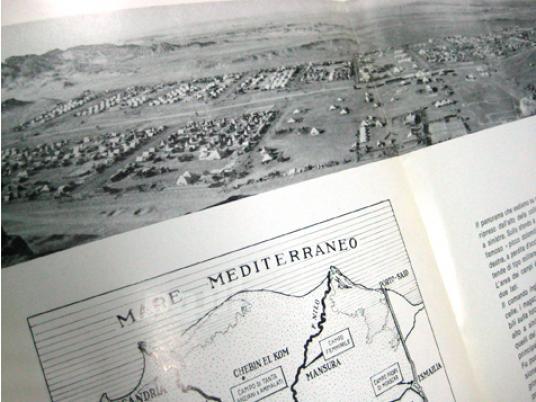

Many Italians travelled to work on the excavation of the Suez Canal where hundreds of them, mainly from Lucca (Tuscany), died in the massive enterprise. (It is worth mentioning that the Canal was in fact designed by an Italian, Alois Negrelli, but De Lesseps ended up with the credit for it). Those who survived decided to stay, while many more arrived at the beginning of the 19th century, and a new Italian expatriate community was born.

Giuseppe Ungaretti, one of the most famous Italian modernist poets, was born in Alexandria and became a representative of the Futurist movement (founded by F.T. Marinetti, another Italian Egyptian).

The Alexandrian Alvise Orfanelli contributed to the birth of cinematography in Egypt and to the rise of a generation of actors (such as comedy icon Togo Mizrahi), photographers, filmmakers and musicians who developed a cinema industry that advanced in parallel with the Italian cinema’s golden years. He also helped Youssef Chahine get into the film business.

Some of Egypt’s architectural landmarks — such as the Corniche of Alexandria, planned by Italian architect Pietro Avoscani, and the grand Mosque of Abul Abbas al-Murci and Omar Makram Mosque in Tahrir, both designed by Mario Rossi in the late 1920s — stand as monuments and memorials of this interrupted story, bearing the testimony of a cosmopolitan history when it was no scandal if a Catholic foreigner was the chief architect of awkaf (Islamic endowments).

Traces of the passage of Italians in Egypt not only can be found under layers of soil and rubble in archaeological sites or in the names of the families that populate the Latin Cemetery of Alexandria.

The mark of the Italian presence can still be heard in the voices echoing from the streets of Egyptian cities, of vendors shouting “Roba vecchia,” mechanics arguing about a “manovella,” or tailors asked to sew up a pair of “guanti.” Those words have become part of the Egyptian vocabulary and, like many other aspects of the Italian culture, are continuously transmitted through oral memories and daily practices.

Many of the Italians in Egypt left the country during World War II and a second wave returned (or travelled for the first time) after Nasser’s nationalization program in 1956, but there are still a few hundred witnesses to give some anecdotes of a serene and seemingly prosperous past.

Just by browsing through the annual diaries of the Italians in Egypt in the 1920s, stored in the library of the Italian Cultural Institute, one can immediately catch a glimpse of the scale of the community and of the depth of its involvement in the national economy with large and small businesses.

“There were almost 60,000 Italians born in Egypt and of Italian-Egyptian descent before the war. Then they started leaving. It was the beginning of the end,” says Antonio, a 40-year-old jeweler of Italian and Greek origins who thinks of himself as an Egyptian Arab. “They paid a high price for being Italian.”

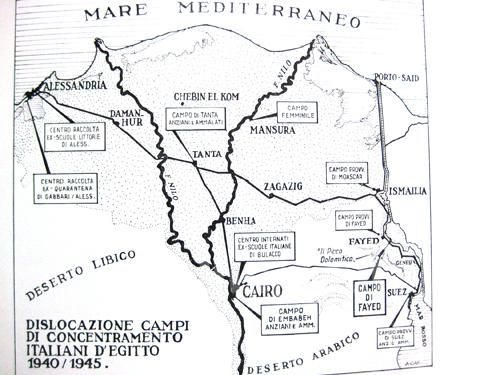

Nearly 8,000 Italian-Egyptians were interned in concentration camps by the British occupiers who feared sabotage attempts after the Italian army first attacked Egypt in 1940. Before that, they were also interned upon the Italian entrance to the war. However, this side of the story is rarely told, neither in Italy nor in Egypt.

“Ever since the early 1900’s until the Second World War, Italians have seen Egypt as an opportunity for work and a refuge from war and hardship. Indeed that’s what it was,” Antonio continues. “Alexandria was a preferred destination for people fleeing the revolts in Italy and persecution of socialists, anarchists and even atheists.”

It was normal for those born at the beginning of the century to think of the Mediterranean as an area containing many nationalities.

Differences were made evident after the start of Nasser's nationalization program because in order to build a renewed Egyptian identity there was a need to affirm its uniqueness and cultural purity as opposed to other nationalities. Nasser took inspiration also from Italy’s Mussolini where a similar process had taken place: the unification and simplification of cultural and linguistic complexity in the peninsula into a coherent and solid projection of the authentic, heroic, patriarchal, Italian race.

“Our families didn't feel discriminated against because they had different habits, as one might think, because actually our culture is very similar, or at least, it was… a strong sense of family values, hard work, peaceful living and a sort of laziness… but not in a negative sense, rather as a joy for the pleasures of life,” Antonio says. “The beauty in our community was that we could work, study, pray together. Egyptians, Italians, Greeks, Armenians, etc. Our parents felt that they belonged here. They felt they were part of a project to build the country they loved and made their home.”

There aren’t many affinities between the old community of Italians of Egypt and the more recently formed community of Italian expats working in the field of cooperation, in the diplomatic and archaeological missions and in the hundreds of Italian commercial enterprises. Nor with the younger generation that mostly sees itself as Egyptian and Arab. “Now we (Italians of Egypt) live in a bubble out of time. Our diversity is always marked and reminded. We (Egyptians) have lost the capacity to welcome. Now it’s all about the money,” Antonio says.

After two years of research, Egyptian filmmaker Sherif Fathy Salem and Italian producer Ramona De Marco just completed a long documentary about the Italians in Egypt that has been presented at the Egyptian Academy in Rome. The Egyptian premier will be held in Cairo in October. The Facebook page of the film has quickly become a platform for sharing memories and precious documents and for nourishing people’s desire to learn about their origins.

“The accounts of elderly members of the Italian community are permeated by a deep sense of nostalgia for the good times,” says Salem. “The ones who decided to move to Italy remember the peaceful atmosphere, the contact with the people, the freedom, the mix of cultures and the mutual respect and appreciation for each other's diversity, natives and not.”

“The Mediterranean was perceived as a region that connected all of them: they were naturally incorporated into a welcoming society, appreciated and valorized through the positive values of their culture and through their skills as craftsmen and professionals,” Salem adds. “Everybody was interested in taking part in the community of Egypt and building the country. The sense of belonging made them devoted to the wealth of the country.”

Even though his name in Italian means “French Greek,” Franco Greco always considered himself an Italian of Egypt. He spent 20 years of his life in Rome, but decided to return to his origins and founded a cultural organization, Associazione Nazionale Pro Italiani d'Egitto (ANPIE), to revive the history of the community and to keep cultural memory alive.

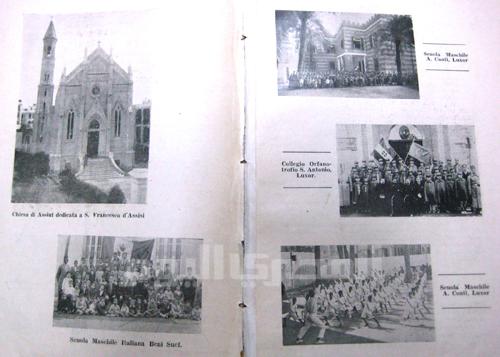

“These fragments of history need to be recuperated in order to know better where we come from and what made us become what we are now. The transmission of culture and history starts from education. That is why, with the disappearance of Italian schools, this part of history and Egyptian culture has been lost… dialogue and understanding starts from there. There were tens of Italian schools scattered everywhere around the country, mostly in Cairo, Alexandria, Port Said, Suez, down until Assiut,” he says.

There are only a couple of schools left, such as Don Bosco in Alexandria, once one of the most prestigious learning centers, and they still have an important role for linking Italy and Egypt culturally and economically.

A few survivors of the community still reunite regularly in the Hospice Vittorio Emanuele in Alexandria or in the courtyard of San Giuseppe Church in downtown Cairo.

“It reminds me of how my family used to spend almost every day at the ‘club’ [Alexandria’s Santa Caterina Church courtyard]. It was a meeting point for all ages. We used to play football for hours, and our parents would play cards or dominoes, the old ladies chitchatting and knitting,” recalls Ivano, a descendent of an old Italian-Egyptian family.

“I remember playing in my grandfather's warehouse; he was famous in the neighborhood because of his ice cream business, and Groppi was his main partner. Like my grandfather, my father was actively involved with the Don Bosco Institute in Alexandria. He used to organize football matches, plays, the Olympic tournament, lo ‘scudetto,’ and was generally well-integrated and well-known in the community," he says.

“He used to tell me that as a young man, he used to meet in Santa Lucia, Asteria, Elite and that Santo Stefano was their favorite beach in Alexandria.”

Ivano remembers that despite everything, his father did not fully master the Egyptian pronunciation. “I have to say that until now, when I go back to Alexandria, people tell me, ‘Abuk kan khawaga’ (Your father was a foreigner). In fact, up until he died, he spoke Egyptian with an Italian accent, even though he was born here!” he smiles.

From the accounts of direct witnesses of this part of Egyptian and Italian history, it seems that living together was seen as an asset rather than a problem to address and eventually solve. “Migration brought a lot of wealth in the first place,” explains Salem. “It was not merely seen as a circulation of capital, but also as circulation of knowledge and culture.”

European and Euro-Mediterranean policies promote integration as the ultimate goal toward living peacefully, but in fact, integration model that is encouraged is one that is more similar to the concept of assimilation, which means adopting the habits, lifestyle and language of the locals instead of maintaining some cultural specificities. That's quite the opposite of what was happening one century ago.

Nevertheless, some claim that conditions were not so ideal, as most Egyptians were not able to enjoy the same privileges as the “Stranieri;” among the rich and foreign communities there was indeed a sense of cosmopolitanism, but it was far from the equality and harmony that the nostalgic celebrate.