On 19 April, the streets of Cairo were once again lined with sit-ins. Within a 1km radius, six different groups–bereft of confidence in those appointed to represent them–staged protests in an effort to air their grievances.

TANTA FLAXS AND OILS

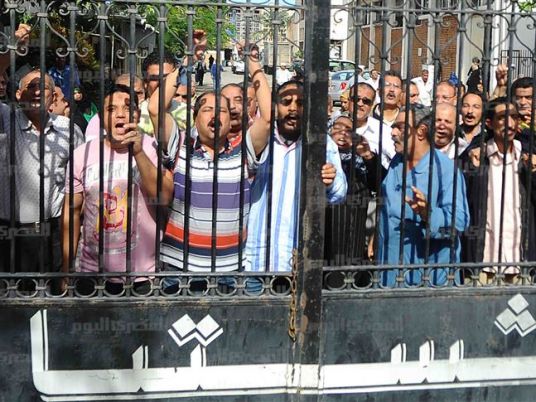

One sit-in cannot even be seen because it has been cordoned off by large numbers of security forces.

On Sunday, State Security personnel completely surrounded roughly 70 workers, sealing them off from the many other sit-ins taking place nearby. Al-Masry Al-Youm was prevented from reaching the site, but was later able to talk to one of the sit-in organizers.

“There is a continuous delay; they keep changing the agreement,” Hisham Okal, member of the Tanta Flax workers union, explained. “The factory owner wants neither to operate the factory nor pay us our retirement packages.”

On 23 February, an agreement was struck between Tanta Flax and Oils factory representatives, government labor officials and the factory’s Saudi Arabian owner. According to the terms of the deal, the factory would be liquidated, unpaid salaries paid out, and all workers provided with retirement packages based on the length of their service tenures.

“I have no faith in the People’s Assembly–it always votes in favor of the NDP [President Hosni Mubarak’s ruling National Democratic Party],” said Okal. “The government’s deceptive promises towards workers will only continue.”

SALEMCO FACTORY

Around the corner, outside the Shura Council (the consultative upper house of parliament), Salemco workers found themselves in similar dire straits.

On 14 March, employees of the Salemco textile factory returned home in smiles. A victory had been won–or so they thought.

The first aspect of the agreement that worker representatives signed with the factory owner was the payment of January salaries. The factory owner had already tried to short-change the workers: a few days after the agreement was reached, owner Mohamed Abdel Halim tried to force workers to sign a document stating that they had received their salaries in full, although LE150 had been subtracted from each laborer’s wages.

Workers refused to agree to the cuts to their already meager paychecks. Frustrated, they again hit the streets.

“All these issues are mere words on paper,” said union head Subhi Khattab. “It’s the same for the workers of the Amonsito factory, Tanta Flax, the Nubareyya company and Salemco.”

STATE-RUN INFORMATION CENTERS

For employees of state-run information centers, the situation is no different. At their sit-in, they explained how earlier promises made by officials had come to nothing. The group ended a previous strike 15 days ago, but, unable to claim any victories, it too has returned to the streets.

“Two weeks ago, Speaker of Parliament Fathi Surour stated his commitment to solving our problem in 15 days,” said Al-Shazly Mostafa. “But we’re back today since nothing has been solved.”

The equation is a simple one, according to Mostafa: “We’re here to stay until they do something for us.”

NUBAREYYA COMPANY

The situation endured by employees of the Nubareyya Agricultural Services and Land Development Company has involved even more deception.

“Today we’re calling for our rights,” Said Mostafa, one of the company’s 230 employees, told Al-Masry Al-Youm. “Even though this is also our factory, we haven’t been paid in 20 months.”

In April 2008, Egyptian-American dual national Ahmed Diaa el-Din Hussein, who owns a 75-percent stake in the company, abruptly decided to terminate all company operations.

When the government privatized the firm in 1997, workers were given 10 percent of the shares. They later managed to purchase a further 10 percent with a loan that they are currently paying back with interest earned from their 20-percent stake. Therefore, Hussein’s unilateral decision to halt operations has not only led to unpaid wages, but has also placed workers’ corporate investments at risk.

“Can you imagine 20 months without pay?” asked Mostafa. “We also lack health insurance. Our situation is like the siege of Gaza.”

Since the company has halted operations, seven workers have died leaving nothing behind for their dependents in the way of pensions.

According to Nubareyya employees, Hussein Megawir, president of the state-run Egyptian Trade Union Federation, is collaborating with the company owner.

“We have appealed to everyone: the ministry, the courts, the public prosecutor,” said one frustrated employee. “This is a political problem. The owner wants to be given land in exchange for restarting company operations.”

According to Nubareyya engineer Gamal Ahmad Kamal, company employees have three basic demands: payment of unpaid wages, the relaunch of operations, and for the government to appoint an intermediary to negotiate between employees and owner.

Workers say the Egyptian-American company owner once told them, “I am the government. I have US citizenship and can therefore do whatever I want.”

For these workers, the government has failed utterly to either represent them or act in the capacity as impartial mediator. The fact that these workers own significant shares in the company does not appear to have improved their position.

THE PHYSICALLY CHALLENGED

Wesam Eid Hassan is among the group of physically-challenged people now into its 77th day of a sit-in at the gates of the Egyptian parliament building.

According to Hassan, the government has failed to implement a law calling for government support of physically-challenged citizens.

“We have the simplest of requests: government financial support in the purchase of apartments,” Hassan said.

He went on to explain that their sit-in was not merely for the purpose of presenting demands. He and his colleagues also hope to eventually establish a network of physically-challenged citizens that can work together to protect the rights of the country’s physically challenged.

AGRICULTURE MINISTRY

Sharing the sidewalk with the Nubareyya workers is Gowahir Mukhtar el-Agami, a female laborer at the Agriculture Ministry’s land improvement authority.

“We’ve been here for 21 days without anyone meeting with us or addressing our grievances,” el-Agami told Al-Masry Al-Youm. “I had to bring my children because I’ve been here without them for three weeks.”

“I call on the president to get involved in our case,” said Omar Fawzi, another ministry employee. “Because so far, ministers have only made statements while nothing has happened–and we’re left here on the sidewalk.”

The Agriculture Ministry provides only temporary work contracts to these laborers. Protestors informed Al-Masry Al-Youm that their monthly incomes ranged between LE60 and LE100. Like so many others, these workers lack even the most basic employment benefits, including health insurance, bonuses and paid vacations.

All groups of protesters share one thing in common: a strong sense of having been abandoned by the government.

“The minister lied to us, so she can stay home,” Hisham Okal, member of the Tanta Flax workers union said, referring to Minister of Manpower and Immigration Aisha Abdel Hadi. “She has nothing to do with us.”

Manpower Ministry spokesman Ibrahim Ali was not available for comment.

Reuters quoted Investment Minister Mahmoud Mohie Eddin at a 6 April press conference as saying that the protests were simply the result of issues arising from the “management of some companies.”

Since 2004, the investment minister has pushed for economic “reforms” entailing the sell-off of public-sector enterprises and government support for the private sector. The rights of workers, however, have not represented a policy objective, critics complain. Rather, in hopes of attracting greater foreign investment, the government has accepted exceptionally low standards in terms of investor responsibility for labor forces, while failing entirely to monitor work conditions.

“No one is pressuring the investor,” said Salemco worker Abdel Sadiq Awad. “Investors can do whatever they want whether I stay on this street or die.”

At the press conference, the investment minister said: “It is not really part of a trend. Workers have their own demands and when some sort of solution for employer and worker is reached, these protests do not develop further.”

The problem is, solutions are not being sought because the government is failing to penalize investors for breaking agreements reached with employees.

The reason workers and everyday Egyptian citizens are protesting is because they alone are paying the price for economic policies by which the government has failed to support workers and farmers while backing investors to the hilt.

EgyptFeatures/Interviews