Egypt is a massive living organism — a web of ticking clocks, each set to a slightly different millisecond. With approximately 80 million in the country, 18 million of whom are woven into the streets and buildings of Cairo, the traffic of the city may crawl but many would say it is only by the will of God that it continues to flow at all. People are everywhere — driving, jumping off buses, walking, bicycling … ticking minute by minute through the days and nights of the city. Doctors, valets, belly dancers and beggars … Cairo keeps 18 million cogs in one of the world’s busiest wheels. This series takes a magnifying glass to one person, a representative of a job that keeps the city ticking — an eye-level shot that takes you through a day in the life of a cog in the wheel of Cairo. —Nevine El Shabrawy

There’s something eerie about the silence and mild manners of the queue in front of the Mohammed Shaheen Strand Bab al-Louq shop. “Why are you all standing so quiet?” asks the fasakhany, Shady Shaheen Sakr. “Because it’s the fesikh line,” a man answers over his shoulder.

“Perhaps they’re dizzy from the smell,” Shady murmurs.

Thursday night before Sham al-Nessim and Shaheen is doing a brisk trade in the Egyptian salted fish delicacy, fesikh. The infamous odor gusts dryly, with a kind of ancient irreverence, down Noubar Street and past the chrome mannequins and home goods behind glass shop windows.

“The smell isn’t usually this bad,” Shady says. “It’s because we’re so busy. We’re opening the fridges all the time. You come here another month and you won’t smell a thing. We’re so clean, people call us the fesikh pharmacy.”

“But right now when I come home, my wife says, 'Go directly to the bath.'”

Shady is the youngest of three sons of Mohamed Shaheen Shakr, the grandson of his namesake who hauled a fish-drying rack from Minya to Cairo in the 1920s. He set up a rudimentary shop in Khan al-Khalili and later bequeathed money to his son, who expanded the business to Sayeda Zeinab. That shop prospered and the head of the family supported his brothers to open other shops. Shady can now count at least five Shaheen shops owned by the family line. As well as these, there are other Shaheen shops set up by more distant relatives, though Shady is not enthusiastic about their quality control.

Eleven years ago, one side of the family that descended from Shady’s great-grandfather accused the other of selling bad fesikh and risking the Shaheen reputation for quality. The five shops were split 3-2.

“We still don’t talk,” he says.

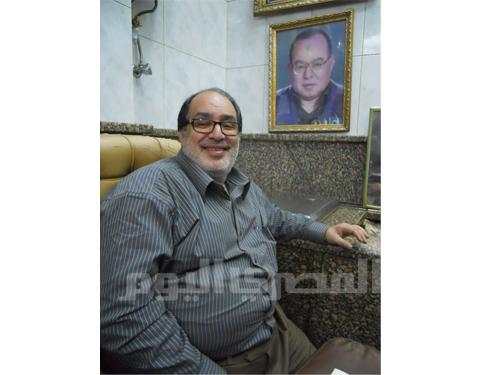

Shady is proud to continue his family’s profession. He and his two brothers work together in the Bab al-Louq shop, and he says they are adamant they will continue doing this instead of separating to each manage their own joint. His father sits behind a desk, at the back, beside the fridges of fesikh stacked lengthways. The serving staff brush past each other, orienteering back and forth between the fridges and the marble countertop. From inside a wreath of cigarette smoke, the father lends his support to their earthly labors. Sham al-Nessim is the time to make money. The shop will go through as much as 1.5 to 2 tons of fesikh in the lead-up to the annual holiday.

“God in his wisdom has made these holidays so we will be busy,” Shady tells us. “Then for the next five months it will be quiet.” He points to the television mounted high up in the corner, showing the white-robed pilgrims circling the Kaaba.

“I will go to the Kaaba,” the father says.

Shady stands to the side, looking less than enthused about his elder’s jubilant annihilation of the summer’s business prospects.

“More people are eating fish on Fridays,” says the young son, carefully upbeat about the business’s long-term prospects.

“It’s becoming less of a seasonal food and more something people eat weekly.”

Taking his cue, a gregarious koshary seller named Ahmed Hosny places an order for several kilograms of their finest barrel-salted fesikh. It is his desire to approach the fridge and pick his own, and he lays down a juicy tip to encourage their participation in the scheme. “I eat a kilogram or a kilogram and a half at a time,” Hosny rasps. “Whenever I feel like it.”

Shady places the dull silver, shrunken salted bouri, also known as mullet, in butcher’s paper and weighs the bouquet on the gleaming analogue scale. One kilogram is LE80.

As a relatively expensive delicacy that difficult to inventory and needs 50 days to prepare, fesikh is especially vulnerable to fluctuations in demand. Estimating demand is key. Last year, directly after the 25 January uprising, Shady’s father made a conservative estimate. But it turned out to be a good Sham al-Nessim.

This year, as Mohamed Shaheen Sakr sat at his desk considering how much bouri fish to order, tear gas canisters were arcing outside of the locked shopfront. A store in the same street was looted.

Yet he predicted a good year. And so far the prediction is holding true.

Shady laughs off the criticism that fesikh is an expensive delicacy for elites. A few years ago, he says, the prominent TV personality Mohamed Saad did a feature report on fesikh and visited the Shaheen Strand Bab al-Louq shop with his camera crew. On the program in which the report aired, he took calls from viewers. “A sheikh called and said fesikh is haraam,” or not allowed in Islam, Shady says.

“Because they use dynamite to catch the fish. And because it’s a rich person’s food,” he said. Saad replied that the way of catching the fish is wrong, but there is nothing wrong with the dish itself. The same goes for rumors of poor hygiene practices. A few vendors are spotting the dish’s reputation, Shady asserts.

But there is also a lot of mud-slinging from health authorities, he complains.

“They’re fighting to convince people not to eat it,” Shady says.

Earlier that day, Egypt Independent had gone looking for fesikh sellers. “They’ll never show you how they make it,” a woman told us with relish as she queued in line outside of one. She shook her head. “Otherwise you would never eat it.”

Fesikh is made and bulk-stored in the Sayeda Zeinab area. Though we are not permitted to access the top-secret facility, Shady is forthcoming about the process. The fish are stacked in large wooden barrels of freshwater, salted and compressed under a free-standing weight for a legislated minimum period of 40 days. The only family secrets are how to stack the fish so each absorbs the same amount of salt, and knowing how salty the fish are at different stages in the process.

“There are now new safety measures to make the process more professional. Before they used to use any kind of dirty rock as a weight,” Shady says.

The US Department of Health and Human Services, however, apparently remains unconvinced by the reforms, Shady says.

“I heard about someone trying to open a fesikh shop in the US,” says Shady, pausing for dramatic effect. “The government closed it down straightaway. Here in Egypt we have different health measure to the US, and it looks like they conflict.

“But give us the standards,” he adds, with a slightly wounded tone, “and we will make clean, filleted fesikh.”

Fesikh, says Shady, goes back to the time of the pharaohs. Bouri bones have shown up at excavated labor camps.

The line under the “Shaheen Kaviar International” sign continues to queue silently. The shop will be open until perhaps 2 am. Then the young scion of a fasakhany dynasty will go home to his wife and 2-year-old son.

Will the son go into the family business?

“Sure,” Shady says.