Egypt is a massive living organism — a web of ticking clocks, each set to a slightly different millisecond. With approximately 80 million in the country, 18 million of whom are woven into the streets and buildings of Cairo, the traffic of the city may crawl but many would say it is only by the will of God that it continues to flow at all. People are everywhere — driving, jumping off buses, walking, bicycling … ticking minute by minute through the days and nights of the city. Doctors, valets, belly dancers and beggars … Cairo keeps 18 million cogs in one of the world’s busiest wheels. This series takes a magnifying glass to one person, a representative of a job that keeps the city ticking — an eye-level shot that takes you through a day in the life of a cog in the wheel of Cairo.

Nevine El Shabrawy

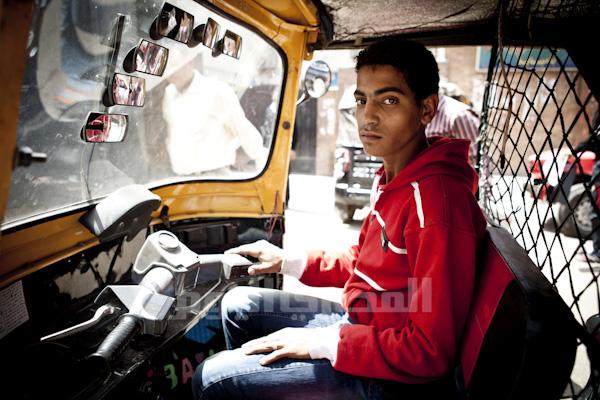

“Women,” Youssef mutters as he swerves his tuk tuk to narrowly avoid colliding with a Mitsubishi. He flicks his wrist at the frowning mother behind the steering wheel and speeds on. “You know why people say women can’t drive?” he asks. “It’s because women can’t drive.”

Youssef is tired and irritable, but understandably so. It’s been an exhaustingly hectic 10-hour shift, the streets are aggressively packed and he’s out of cigarettes. He’s also twelve years old.

“I’ll be thirteen next week,” he states matter-of-factly. He knows the occasion will not be marked by any special celebration. Instead, Youssef’s introduction into teenagedom will unfold much like today and every other day over the past two years. He will be up by 5 am, giving him a little under an hour to pick up his tuk tuk from local entrepreneur Bakha and hit the streets in time for the early morning rush.

“I don’t enjoy the mornings,” Youssef grumbles, sleep lingering in his eyes at 6:15 am. The first few hours of his day may be part of a routine, but it’s still a brutal one, predominantly fixed along a smoggy and slow-crawling path. The starting point is the bustling hub of public transportation and street vendors at the end of Faisal street, where a scattering of tuk tuks graze between herds of larger and louder microbuses. Youssef has barely parked before being approached by the day’s first fare. “The morning customers are boring,” he has no trouble explaining as a young couple in school uniforms climbs in. “I just make the same trip over and over again, taking people out to the main street.”

The main street is Al-Haram, and as far as Youssef and the early hours are concerned, it’s a no-man’s land. For LE1, he will drive customers to its corner, but not beyond for fear of being pulled over. “Traffic officers have a heavier presence this early in the day,” he says. “We’ll wait and see how it goes.” Youssef does not have a driver’s license, for obvious reasons, but ask him for his own reasoning and he’ll offer, “if they give me a license, then they’d have to give one to all the other kids. And there’s just not enough tuk tuks for us all.”

If age is an issue, “it shouldn’t be,” Youssef insists. “I’ve been driving since I was six. I know what I’m doing.”

The same can be said for his cousin, Ali. Two years Youssef’s senior, Ali has served more time behind the handlebars of a tuk tuk, and looks about ready to give it up. “No, I don’t enjoy it,” he says. “But what are you going to do?”

The two boys are fatherless — Ali’s is dead, Youssef offers no further information on his — and they both have siblings and single mothers to support. Besides his daily income (anywhere between LE15 to LE50, although usually more towards the lower end of that spectrum), Youssef’s family also relies on his older brother who “works in a chicken shop and is very lazy.” Ali, being the only male member of his direct family, enjoys no such luxury, having only graduated to the world of improvised public transportation as a means to escape the abuse handed out by his former employer, a mechanic who specialized in forklift repairs.

“I used to get cussed at all the time, all day long hearing my mother called a whore,” he recalls, adding that at times the attacks were more than just verbal. “I put up with it until my family told me I didn’t have to anymore.”

Ali’s new job came in the form of a tuk tuk which he now, for the most part, tries to ignore. “I haven’t picked it up in a few days,” he says, explaining that he prefers squeezing in the front seat with his cousin and taking turns driving since “we both get tired.” Youssef does not seem convinced.

“Bakha is very angry with you,” he warns. “He asked about you again today.”

Ali says nothing and, for a while, neither does his cousin, until the latter adds, “He’s just going to give your tuk tuk to someone else.” It’s a valid point: despite immediate legal and ethical concerns, tuk tuk driving is the rare, relatively lucrative and abuse-free choice on the lamentably long list of options available to young poverty-stricken boys with families to support. As such, the world of child tuk tuk drivers is a surprisingly vicious one — evidenced by the long fresh gash running from the back of Youssef’s neck to the middle of his left cheek.

“There was an argument over customers,” Youssef shrugs. “An older driver cut me with a key.”

Meanwhile, a science-fiction film about children killing each other over food continues to shatter global box office records. It’s likely neither of the boys will ever watch it — their severely limited funds and free time tailored for the most meager of leisurely allowances. “After my shift I’ll either play soccer with friends, or go swimming at the youth center if it’s not too late,” Ali says, inviting Egypt Independent along for the latter option. Most days, Youssef will accompany his older cousin, although there are times when he’ll “just ride along with the nightshift drivers. They’re my friends, so I enjoy spending time with them, but sometimes they’ll get tired of driving and I’ll take over.”

“It’s a good way to make some extra money,” he says.

By noon, a two-hour lull in the day is coming to an end, and Youssef is back on the move, sharing his narrow front couch with his cousin and an awkwardly positioned reporter. An older veiled woman with several shopping bags, and a teenage schoolboy — separate fares — share the backseat. Encouraged by the absence of traffic police, Youssef makes his way down Al-Haram street, reenergized after a small, 4LE lunch of fuul, falafel, eggs and eggplant.

“Look at that old hotel,” he points to a charred and burnt-out skeleton of a building, a sign on its side reading Europa Hotel. “That place was a whorehouse. That’s why it burst into flames.”

“You mean someone set fire to it, like extremists?” this reporter asks.

“No, it just set itself on fire,” he smiles cheerfully. “Because of all the sins.”

The radius of Youssef’s route has swelled throughout the day. “When there’s no cops,” he boasts, “I can go anywhere. I take people to Kerdasa, el-Shishiny, Bahgat, el-Ezba, el-Bourah, Ghatati, el-Ka’abeesh, the Hill (el-Hadaba), the New Street … everywhere.”

While “everywhere” might be limited to the district of Al-Haram, these further journeys give Youssef a sense of liberation the morning hours typically deprive him of. They may not be far apart, but, as he explains it, “going to these different places is definitely more interesting than the morning routine. At least the scenery changes.”

As do the passengers, but Youssef isn’t concerned with them. “They just sit in the back and keep their mouths shut,” he says. “I don’t talk to them much and they don’t usually have anything to say to me.” Instead, Youssef will either depend on his cousin for company, or his radio for entertainment, which, for most of the day, had been appropriately blaring the strained screeching of a child singer.

“What do you want me to tell you?” the radio asks, in echoes. “Is it not enough to tell you I love you / To tell you that I cherish you / Who misses me but you, father?”

“That’s Mohamed Rizk,” Youssef responds, pointing to the radio. “He’s really good. He’s younger than me, too.”

The song is a sad one, a melancholic melody backed with sobbing strings. Like Youssef’s tuk tuk, it may be driven by a child, but there is nothing remotely childish about it, not even the stuffed teddy bear balanced between the handlebars.

“That’s not mine,” Youssef dismisses the raggedy creature. “Bakha must have put it there. I think it’s silly.”

Unlike most children, Youssef isn’t eager to grow up, but that’s because he already has. Regardless of his actual age, the young driver knows his childhood is now a thing of the distant past. “I’m not that young,” he insists. “I have friends who are younger than me and who also drive tuk tuks for a living. Both Hanafy and Saber are 10, and Abou Talaat just turned nine.”

Things could be worse, Youssef knows. He and the other kids might fall in with an abusive employer, or a more physically demanding job. Or, they could have no work at all.

For the time being, there’s school, which Youssef attends “when there’s enough time to,” and there’s work, which is a priority. The twelve year-old talks of one day “giving up the tuk tuk” but, having been forced by circumstance to join the work force this early on, he remains realistic.

“The hardest thing about my job,” he says, “is shifting gears.”