Downtown’s Cinema Culture Center celebrated International Woman’s Day this month by screening five films by female filmmakers from the Iranian Makhmalbaf family. While filmmaking in Iran remains politically sensitive, the country’s women filmmakers have produced an impressive body of work in recent years, garnering well-deserved critical acclaim internationally.

"Despite being no more than ten years on the professional scene, working under difficult conditions and facing various limitations, [Iranian women filmmakers] have had greater success than men in a more realistic portrayal of both women and men in Iran," states Shahla Lahiji, founder and director of Iran’s Roshangaran Publishing and Women’s Studies Center, in her essay, "Portrayal of Women in Iranian Cinema: An Historical Overview" (2002).

Iranian cinema is a burgeoning industry with a long history and still-conflicted status. Low-grade popular commercial films are produced on a regular basis, while Iranian art films continue to win praise at international film festivals.

The "Iranian New Wave" of cinema–often said to have begun in 1969 with the release of Dariush Mehrjui’s The Cow–made fresh, political and socially-conscious films with a poetic visual language. Women fought to participate in this movement as both actresses and directors, intent on expressing their views, concerns and aspirations. The most notable figures of the Iranian New Wave are directors Abbas Kiarostami–who put Iran on the world cinema map when he won the Cannes Film Festival’s Palme d’Or for Taste of Cherry (1997)–Jafar Panahi, Bahram Beizai, Mohsen Makhmalbaf, Khosrow Sinai and Samira Makhmalbaf.

In the aftermath of the 1979 Islamic revolution, many films, both Iranian and foreign, were banned or heavily censored, while hundreds of cinemas were burnt down. The country’s current creative climate is still indicative of a repressive regime. Earlier this month, Panahi was arrested, along with members of his family, for shooting what loyalists termed an "anti-regime" film.

Panahi addressed women’s issues directly in his compelling The Circle (2000), which tells the story of several women trying to work their way through their unjust predicaments, and his most recent film, Offside (2006), which tells the story of a group of female football fans arrested for disguising themselves as boys in order to sneak into a football match. Other notable films by famous male Iranian directors that focus on women include Gabbeh (1996) by Mohsen Makhmalbaf; Ten (2002) by Abbas Kiarostami; and Baran (2001) by Majid Majidi.

The restrictive codes that came with the Islamic revolution were gradually liberalized over three stages, according to Tirza Kugler, lecturer at Tel-Aviv University’s film and television department. The first stage, employing rigorous censorship, involved the disappearance altogether of unveiled women from both Iranian and foreign films. In the second stage, women appeared on the screen as secondary characters in passive roles. At the same time, aesthetics and grammar rules of seeing and hiding were developed, prescribing long clothing that covered female bodies and prohibiting all physical contact–or "direct gazing"–between the sexes.

The need to overcome these rules brought about the development of cinematic tricks, notes Kugler, where alternative ways of gazing were developed–from unfocused looks to desireless gazes–in order to avoid close-ups emphasizing women’s physical beauty. In the third stage, from the end of the 1980s, with the relative liberalization that came with the election of moderate president Mohamed el-Khatami, women achieved more independence as filmmakers and succeeded in portraying more prominent characters with a will of their own; their on-screen presence became more open, and their faces and expressions were exposed.

The Iranian Ministry of Culture’s 1996 guidelines still forbid showing tight feminine clothes, any part of a woman’s body except the face and hands, any physical contact–or tender words–between men and women, as well as foreign or joyous music. These restrictions have tested the ingenuity of the country’s filmmakers, giving rise to innovative and symbolic storytelling styles–and women directors have been at the forefront of the movement.

Rakhshan Bani-Etemad is considered Iran’s premier female director, and her films and documentaries have received praise at international film festivals and have proven popular with Iranian critics and audiences. She tackles the issues of poverty, crime, divorce and polygamy in such works as Nargess (1992), the story of Afagh, an aging thief trying to cling to her fading beauty and younger lover; The May Lady (1998), about a divorced mother forced to choose between her need for companionship and her son’s respect; and Under the Skin of the City (2001), the postmodernist story of Tooba, a factory worker who shoulders the burden of her problematic family. In recognition of her socially-conscious work, Bani-Etemad received the Prince Claus Award in 1998.

Feminist filmmaker Tahmineh Milani is another one of Iran’s few high-profile female filmmakers. Constantly at odds with the government, her often melodramatic films usually deal with women’s rights and the Islamic revolution, featuring fearless female leads confronting an oppressive regime. Her fifth film, Two Women (1999), the story of a scholarly woman whose spirit is crushed by the male characters that inhabit her life, took seven years to be approved. She was arrested in 2001 for her subsequent film, The Hidden Half (2001)– about a judge who discovers that his wife was once a revolutionary–before an international uproar among filmmakers led to her release. Despite her feminism, she is famous for stating that a filmmaker’s gender is insignificant when considering cinematic creations that reflect feminine perspectives and experiences.

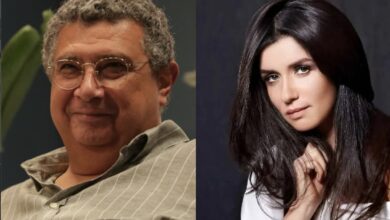

Samira Makhmalbaf, daughter of prolific filmmaker Mohsen Makhmalbaf, is also one of the best-known female film directors in Iran today. She acted in her father’s film The Cyclist (1987) at the age of seven and left high school at 14 to learn cinema under his tutelage at the Makhmalbaf Film House. At the age of 18, she became the youngest director to participate in the official competition of the 1998 Cannes Film Festival with The Apple (1998), which follows two sisters recently released from the captivity imposed on them by their parents. Samira made her second feature film, Blackboards (2000), about the trials of two travelling teachers in Kurdistan, and for the second time participated in the official competition at the Cannes Film Festival as the youngest director in the festival’s history, this time winning the Special Jury Prize.

The Cinema Culture Center focuses on Samira Makhmalbaf in it’s program this month. It will also screen Buddha Collapsed Out of Shame (2007), the story of a young girl whose desire to learn leads her into dark territory, by Samira’s sister, Hana Makhmalbaf, as well as Marzieh Mashkini’s The Day I Became A Woman (2000), considered by Kugler to be "the ultimate cinematic representation of the Iranian woman of our time," about turning points for three women at different stages in their lives. Hana Makhmalbaf and Marzieh Mashkini are also graduates of the Makhmalbaf Film House.