Stakes are high for the meeting, which takes place every five years and is known as China’s third plenum. It has historically been a platform for the party’s leadership to announce key economic reforms and policy directives.

China is grappling with a property sector crisis, high local government debt and weak consumer demand — as well as flagging investor confidence and intensifying trade and technology tensions with the United States and Europe.

Those challenges were underscored by its latest economic growth data, which were announced Monday. China’s gross domestic product expanded by 4.7 percent in the April to June months, compared to the previous year.

That represents a slowdown from the 5.3 percent growth reported for the first quarter and also missed the expectations of a group of economists polled by Reuters who had predicted 5.1 percent expansion in the second quarter.

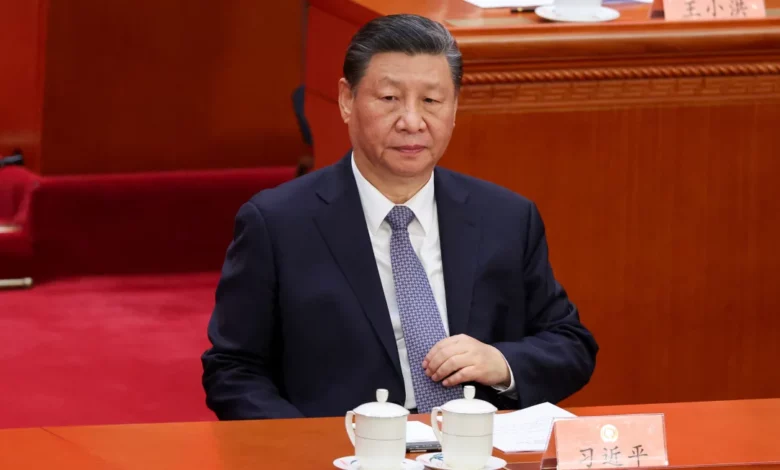

Economic problems on the back of years of stringent pandemic controls have triggered mounting social frustration, as well as questions about the direction of the country under Xi Jinping, its most powerful leader in decades.

Those questions have been underscored by a recent shake-up in the upper echelons of Xi’s government that saw three ministers and a handful of top military officers removed from posts or investigated, a situation that some observers of China’s opaque political system believe contributed to the plenum’s delay.

How Xi and his top officials choose to address the country’s economic challenges will have significant impact on whether they can continue to raise quality of life, and public confidence, within China.

They could also have a broad impact on the country’s role in the global economy and how willing foreign investors will be to do business there as uncertainties, including the outcome of the upcoming US presidential election, loom.

Here’s what to expect at the four-day gathering, which begins Monday.

Big changes?

About 200 members of the party’s Central Committee leadership body as well as 170 alternate committee members are gathering in Beijing to approve a document laying out a plan on “deepening reform” and advancing “Chinese-style modernization,” according to state media.

Past third plenums have delivered sweeping reforms.

The meeting in 1978 was linked to the landmark shift toward the “reform and opening” of China’s economy, while Xi’s first third plenum as leader in 2013 set in motion the move to dismantle the decades-old one child policy.

But observers of China’s opaque political machine don’t believe there will be fundamental economic reforms this time around.

Instead, they will be watching for more targeted efforts to address structural economic issues and social problems — and to enhance China’s technological self-reliance at a time when it faces a raft of restrictions on access to technology driven by the US.

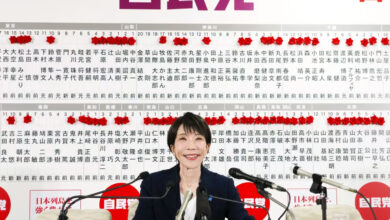

This is Xi’s third time overseeing this meeting after he extended his rule into a norm-breaking second decade at the last Party Congress in 2022.

Speculation has swirled around why the meeting, which was widely expected to take place last fall, is only happening now.

Some observers suggested the flagging economy and internal disagreement over how to address it, as well as the high-level personnel shake-ups that cast a shadow over Xi’s third term, could have played a role.

Economic challenges

The high debt loads held by local governments and their shrinking income, linked to an ongoing property sector crisis, lie at the heart of China’s current economic woes.

They’ll also be looking for signals on a new direction for real estate development and property sector policy in the wake of the industry crisis that’s seen dozens of Chinese developers default on their debts, which has, in turn, devastated investors, homebuyers and construction workers.

Observers will be watching for fiscal reforms, especially around taxation and government spending, that could reduce pressure on local governments and bolster their revenue.

Many also say the government should take steps to boost consumer spending and increase household income, including potential reforms to change rural land ownership and China’s restrictive household registration system, as well as to expand social safety nets in a country grappling with high medical costs and a rapidly aging population.

Xi has acknowledged economic hardship in China, saying in a New Year’s speech that “some people” had “difficulty finding jobs and meeting basic needs.” In a May speech, he also stressed that the party should “do more practical things that benefit the people’s livelihood,” adding that reform should give people a sense of “gain.”

While chasing rapid economic growth is “no longer Beijing’s singular priority,” Asia Society Center for China Analysis experts Neil Thomas and Jing Qian wrote last week, Xi likely recognizes that his priorities of national security and tech self-reliance “must co-exist with a baseline level of growth that sustains consumption, investment, social stability, and his own political security.”

Tech push

Tech self-reliance has become a key focus for Beijing as the US and its allies have moved to limit China’s access to high-end technologies, citing their own security concerns.

The plenum is expected to greenlight more government coordination around Xi’s plan to build China into a “science and technology power,” both in terms of innovation as well as industry.

But such a focus also threatens to heighten frictions with the West.

The EU and the US have recently slapped hefty tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles, saying they are unfairly subsidized by the government and flooding global markets. Any moves this week that bolster the production of such high-end green technologies, which also include goods like solar panels or batteries, could further inflame the issue.

Meanwhile, global investors will be looking for Beijing to make good on promises to further open up its market, even as many firms have become more wary of doing business in the country as Xi has prioritized heightened state control and security.

The plenum could also see the formal ousting of top Communist Party officials who have been ensnared in opaque disciplinary investigations or removed from posts without explanation, some of whom were linked to an apparent military purge.

Li Shangfu, China’s former defense minister who was fired from his role in October and expelled from the Communist Party following a corruption investigation, will likely be formally removed from the Central Committee.

Observers will be watching closely for any similar movement around other ousted government and military officials, including former Foreign Minister Qin Gang, People’s Liberation Army Rocket Force commander Li Yuchao and his political commissar Xu Zhongbo.