It is Friday evening and a Jewish family’s preparations for the Sabbath, the holiest day of the week, are in full swing. In the living room, everyone has gathered around the big table for the traditional celebration as tantalizing aromas of hot food drift through from the kitchen.

The youngest son breaks the unsalted bread, then reads from the Tanakh as his father pours the obligatory glass of red wine to be passed around the table. Although it may look very like the kind of typical scene to be found in thousands of households across Israel every weekend, there is one important difference here. This one is happening in Iran.

Read more: Jewish heritage in Iran was ‘always better than in Europe’

The last rays of winter sunshine are just dipping out of sight behind the Alborz mountains on this cold January day in Tehran. It is the last day of the week, which in Iran begins on Saturday. There are no major buildings — and certainly none of a religious nature — to punctuate the skyline in this part of town, with its plethora of small kiosks and supermarkets.

There is no doubt that things have changed since the revolution. Prior to 1979 there were 10 times more Jews living in Iran than there are now. Despite the troubled relationship with Israel however, Iranian politicians and clergy are always at pains to stress that they have no quarrel with the Jews, only with the state of Israel. As Ayatollah Khomeini put it shortly after the revolution: “We recognize our Jews as separate from those godless Zionists.”

It is a quote that is still to be found today on every Jewish prayer house. Something that the Iranians, no matter which religion they belong to, have internalized. In contrast to the situation in German-speaking countries, Jewish institutions in Iran do not require any security arrangements. Iran has not seen a single attack on a Jewish building.

Everyday freedoms

After several major waves of emigration, the number of Jews living in the country has now stabilized. According to Israeli statistics, only 1,100 Jews migrated to Israel from Iran between 2002 and 2010. For those who remain, prospects are surprisingly positive. They have been granted official minority status, a permanent seat in parliament and freedom to practice their religion. They have their own butchers’ shops, their rabbis are permitted to conduct weddings, and the community can produce and drink its own wine for the Sabbath — and that, even though alcohol is otherwise subject to strict prohibition in Iran.

“We love Iran and we are able to live in freedom here,” says Eliyan, the Musazedeh family’s eldest daughter. The 24-year-old lives with her family near the center of Tehran, the only Jewish family in the apartment block. “Our neighbors know we are Jews, but it isn’t an issue. The society here in general does not have problem with us being Jews.”

Although Jews in Iran are not allowed to hold leading positions in state institutions such as the army, police or secret service, their lives are otherwise as free of restrictions as those of other Iranians.

A memorial was erected to Jewish martyrs of the Iran-Iraq war by President Hassan Rouhani, and for some years now, Jews have had the right to take off from work on the Sabbath. “There have been a couple of occasions in the past when I have been looking for work and didn’t get the job after saying at the interview that I was Jewish,” Eliyan admits. “It wasn’t because they didn’t want to hire a Jew, but rather because they knew they would be legally obliged to give me Saturday off if I wanted it.”

So, if a Jew in Iran does not get a job, it’s not because of their religion, it’s because the law is on their side and employers are obliged by law to give them an extra day free per week, she explains. “There is no anti-Semitism in Iran. Iran is a multi-ethnic and very diverse country and Iranians are proud of that diversity and history.”

‘Too fat, too old, or both’

As the eldest daughter, the pressure is now on her to start thinking about a future marriage partner. “My father is always trying to find potential candidates from families we know, but I turn them all down. They are all well off, but either too fat, too old, or both.” Eliyan’s dilemma is compounded by the fact that, as the eldest, she must marry first; only then will her two sisters, Nazanin and Yasaman, be allowed to date.

Friday evening Sabbath celebrations usually take place at home. Although it is only a few streets away, the Musazadeh family rarely goes to the local synagogue. Three of Eliyan’s cousins, Rafael, Ariel and Avraham, have arrived for today’s Sabbath. Mother Anita has been busy preparing and cooking the food all afternoon, because any form of work, or use of fire or electricity, is forbidden during the Sabbath, which begins at nightfall.

The Musazadehs generally celebrate Sabbath at home on Friday evenings rather than going to the nearby synagogue

The Musazadehs generally celebrate Sabbath at home on Friday evenings rather than going to the nearby synagogue

Despite that, Anita will cook the rice in the evening. “I can’t serve cold rice for dinner,” she says — a sentiment that no Iranian would argue with. The only family member who is regularly allowed to ignore religious laws is the father of the family, Shahrokh, who runs a small business selling women’s shoes and bags. He spends Sabbath evenings on the couch, zapping his way through the Iranian satellite TV channels, while Anita is kept busy between the kitchen, her three daughters, youngest son Ariyan and the family dog, as well as seeing to the food.

It is at times like this that it becomes clear why Iranian Jews are Iranians first and Jews second. Like most Iranians, the Musazadehs have an almost unconditional love for their country. Like other Iranians, too, however, they also find the economic situation hard to bear. “I would like to go abroad, to Europe maybe, or Canada,” says Eliyan. “You cannot find any well-paid jobs in Iran anymore, and the situation is getting worse every year.”

No future in Iran

It is a view shared by many young people in Iran. Many no longer see a future for themselves in the country and are keen to go abroad, at least temporarily, for work or study. “Neither America nor Israel would be an option for me. A relative of ours once went to the US and she hated it. She didn’t take to the culture or the fast pace of life at all.”

One of Eliyan’s aunts, who died last year, visited Israel for medical treatment. “As Jews we have the opportunity of emigrating to Israel, and even receiving around $15,000 (€13,300) from the Israeli government for going. But if we went there, we would have to speak Hebrew, something we only ever do in religious contexts. That would be very strange for us and I would not feel at home there. Iran is our home.”

As the food is brought to the table, Shahrokh brings out another bottle of homemade wine. Everyone takes up a glass while Ariyan, reads a prayer. The meal consists of salad with pomegranate seeds, the obligatory Sabbath fish, Iranian barbari bread, and gondi (chicken and chickpea dumplings), a dish that is particular to Persian-Jewish cuisine.

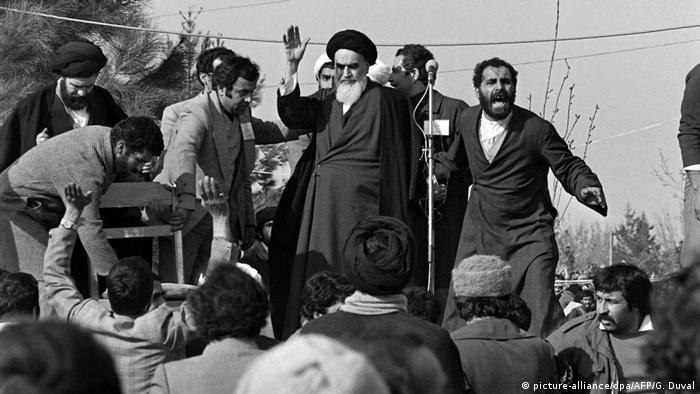

Many Jews left Iran as a result of the 1979 revolution, which led to the founding of the Islamic republic

Many Jews left Iran as a result of the 1979 revolution, which led to the founding of the Islamic republic

Despite the positive circumstances for Jews in Iran, tens of thousands of them seized the welcome opportunity provided by the 1979 revolution to turn their backs on their homeland forever. Eli Hoorizadeh, an uncle of the Musazadehs, seeing little prospect in Iran of realizing his ambition of becoming a rabbi, left the country in 1980. Today he lives in Jerusalem with his wife and 13 children. “He is happy to have left Iran and has no interest in coming back. Israel has become the home for him that Iran could never have been,” says Eliyan.

As the long evening draws to a close, and another pot of tea brews in the kitchen, the family sit together in the living room engrossed in the Iranian version of “Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?”.

The idea, propagated by the West, that Iranian Jews are suffering under the country’s government is something Eliyan has little patience for. When asked about her hopes for the future, she answers: “If I as a Jew could request anything of the Iranian government, I would ask for some nice, handsome Jewish boys, so I could finally find someone to marry.”

Jan Schneider is a pseudonym.

This article was originally published at DW’s partner site Qantara, which focuses on dialogue with the Islamic world.