In middle school, Junior Alvarado often struggled with multiplication and earned poor grades in math, so when he started his freshman year at Washington Leadership Academy, a charter high school in the nation’s capital, he fretted that he would lag behind.

But his teachers used technology to identify his weak spots, customize a learning plan just for him and coach him through it. This past week, as Alvarado started sophomore geometry, he was more confident in his skills.

“For me personalized learning is having classes set at your level,” Alvarado, 15, said in between lessons. “They explain the problem step by step, it wouldn’t be as fast, it will be at your pace.”

As schools struggle to raise high school graduation rates and close the persistent achievement gap for minority and low-income students, many educators tout digital technology in the classroom as a way forward. But experts caution that this approach still needs more scrutiny and warn schools and parents against being overly reliant on computers.

The use of technology in schools is part of a broader concept of personalized learning that has been gaining popularity in recent years. It’s a pedagogical philosophy centered around the interests and needs of each individual child as opposed to universal standards. Other features include flexible learning environments, customized education paths and letting students have a say in what and how they want to learn.

Under the Obama administration, the Education Department poured $500 million into personalized learning programs in 68 school districts serving close to a half million students in 13 states plus the District of Columbia. Large organizations such as the Melinda and Bill Gates Foundation have also invested heavily in digital tools and other student-centered practices.

The International Association for K-12 Online Learning estimates that up to 10 percent of all America’s public schools have adopted some form of personalized learning. Rhode Island plans to spend $2 million to become the first state to make instruction in every one of its schools individualized. Education Secretary Betsy DeVos also embraces personalized learning as part of her broader push for school choice.

Supporters say the traditional education model, in which a teacher lectures at the blackboard and then tests all students at the same time, is obsolete and doesn’t reflect the modern world.

“The economy needs kids who are creative problem solvers, who synthesize information, formulate and express a point of view,” said Rhode Island Education Commissioner Ken Wagner. “That’s the model we are trying to move toward.”

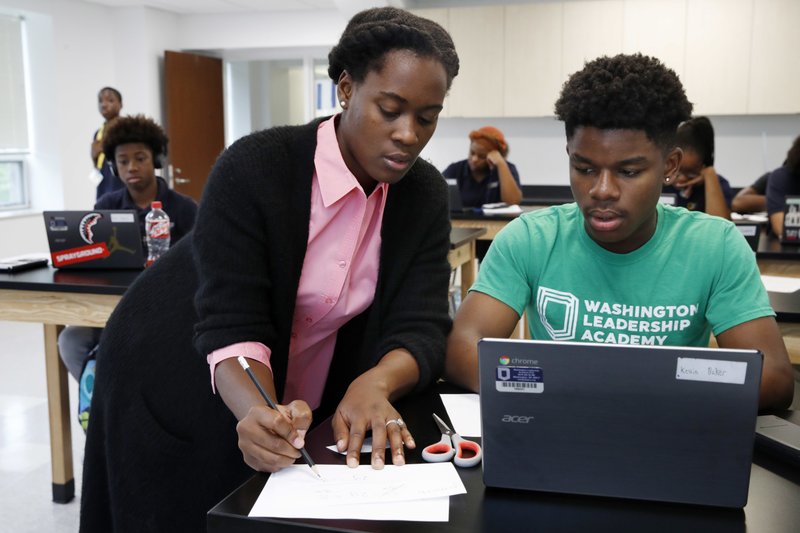

At Washington Leadership Academy, educators rely on software and data to track student progress and adapt teaching to enable students to master topics at their own speed.

This past week, sophomores used special computer programs to take diagnostic tests in math and reading, and teachers then used that data to develop individual learning plans. In English class, for example, students reading below grade level would be assigned the same books or articles as their peers, but complicated vocabulary in the text would be annotated on their screen.

“The digital tool tells us: We have a problem to fix with these kids right here and we can do it right then and there; we don’t have to wait for the problem to come to us,” said Joseph Webb, founding principal at the school, which opened last year.

Webb, dressed in a green T-shirt reading “super school builder,” greeted students Wednesday with high-fives, hugs and humor. “Red boxers are not part of our uniform!” he shouted to one student, who responded by pulling up his pants.

The school serves some 200 predominantly African-American students from high-poverty and high-risk neighborhoods. Flags of prestigious universities hang from the ceiling and a “You are a leader” poster is taped to a classroom door. Based on a national assessment last year, the school ranked in the 96th percentile for improvement in math and in the 99th percentile in reading compared with schools whose students scored similarly at the beginning of the year.

It was one of 10 schools to win a $10 million grant in a national competition aimed at reinventing American high schools that is funded by Lauren Powell Jobs, widow of Apple founder Steve Jobs.

Naia McNett, a lively 15-year-old who hopes to become “the African-American and female Bill Gates,” remembers feeling so bored and unchallenged in fourth grade that she stopped doing homework and her grades slipped.

At the academy, “I don’t get bored ’cause I guess I am pushed so much,” said McNett, a sophomore. “It makes you like you need to do more, you need to know more.”

In math class, McNett quickly worked through quadratic equations on her laptop. When she finished, the system spitted out additional, more challenging problems.

Her math teacher, Britney Wray, says that in her previous school she was torn between advanced learners and those who lagged significantly. She says often she wouldn’t know if a student was failing a specific unit until she started a new one.

In comparison, the academy’s technology now gives Wray instant feedback on which students need help and where. “We like to see the problem and fix the problem immediately,” she said.

Still, most researchers say it is too early to tell if personalized learning works better than traditional teaching.

A recent study by the Rand Corporation found that personalized learning produced modest improvements: a 3 percentile increase in math and a smaller, statistically insignificant increase for reading compared with schools that used more traditional approaches. Some students also complained that collaboration with classmates suffered because everybody was working on a different task.

“I would not advise for everybody to drop what they are doing and adopt personalized learning,” said John Pane, a co-author of the report. “A more cautious approach is necessary.”

The new opportunities also pose new challenges. Pediatricians warn that too much screen time can come at the expense of face-to-face social interaction, hands-on exploration and physical activity. Some studies also have shown that students may learn better from books than from computer screens, while another found that keeping children away from computers for five days in a row improved their emotional intelligence.

Some teachers are skeptical. Marla Kilfoyle, executive director of the Badass Teachers Association, an education advocacy group, agrees that technology has its merits, but insists that no computer or software should ever replace the personal touch, motivation and inspiration teachers give their students.

“That interaction and that human element is very important when children learn,” Kilfoyle said.