When French President Emmanuel Macron and German Chancellor Angela Merkel meet President Donald Trump in the White House within days of each other, it will represent the most high profile European push yet to try to convince him to remain in the Iran nuclear accord, which he has repeatedly branded as the “worst deal ever.”

The Franco-German charm offensive is certainly the most visible effort to prevent the Trump administration from pulling out of the deal which was signed in 2015. But it is only the tip of the iceberg.

Negotiations are ongoing between the so-called E3 group, Germany, France, Britain, and the US to reach an agreement that would satisfy the demands the president made in his January 12 ultimatum when he last waived sanctions against Iran. Last week, hundreds of European legislators wrote an open letter urging the US Congress to support the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), as the Iran nuclear accord is officially called.

But the concerted European push, according to high-ranking former US officials and Washington-based European diplomats, may well fall short of its goal to persuade Trump ahead of the May 12 deadline to renew the sanctions relief for Iran, a key step in keeping the nuclear deal alive.

Pessimistic outlook

“Unfortunately, I don’t know anyone in the United States who is particularly optimistic that the sanction waivers will be signed again at the relevant time,” said Laura Holgate, who served as US ambassador to the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) until President Trump’s inauguration in January 2017.

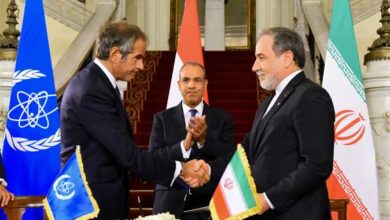

The IAEA, which is tasked with monitoring and verifying Tehran’s compliance with the Iran agreement, has so far concluded that the country did comply with the accord.

Elizabeth Rosenberg, a former senior sanctions official at the Treasury Department, shared Holgate’s skepticism about the chances that the US will remain in the agreement — even if negotiators’ succeed in hammering out an agreement.

“I feel much less hopeful about whether the US administration will in the end continue to fulfill its obligations under the deal, which is to say I am doubtful that the US will stay in the deal,” said Rosenberg.

“Flaws” to fix

European diplomats who requested not to be named in order to talk openly about this sensitive issue expressed hope that negotiators might be able to find common ground, but remained skeptical whether this would ultimately suffice for Trump.

“I am hopeful, but not confident,” said one. “No one knows what Trump will do in the end.”

A diplomat of another European country said he was hopeful that a joint document could be negotiated, but emphasized that even US officials these days cannot say for certain whether the president would accept it.

Of the three “flaws” Trump demanded to be fixed in order for him to extend the Iran sanctions relief — Tehran’s ballistic weapons program, expanded IAEA access to Iranian facilities and the so-called sunset clauses — the latter is the main stumbling block, say the US and European experts.

Bolton and Trump

While the Trump administration effectively wants to extend the limits on Tehran’s nuclear program, which according to the accord are set to fully expire by 2031, the Europeans are reluctant to do so, saying this would de facto be a renegotiation of the agreement.

From a US perspective, there are further complications regarding negotiations with the E3. Richard Nephew, the lead sanctions expert for US negotiations with Tehran in the Obama administration where he also served as the National Security Council’s Iran director, questions to what extent Germany, France and Britain can really speak for all other EU countries, some of which favor a softer approach vis-à-vis Tehran than the E3.

“Germany cannot force sanctions retaliation upon Italy, and Britain, with everything that’s going on with Brexit, they sure can’t force any EU response,” he said.

But the core of the problem, agreed the former and current officials from the US and Europe, is Trump’s long-standing fundamental opposition against the Iran accord, a view which is only likely to be amplified by Trump’s new hard-line National Security Advisor John Bolton who in an editorial three years ago advocated “To Stop Iran’s Bomb, Bomb Iran.”

“There is so much emphasis in President Trump’s track record as a candidate and in office directed even in an ideological manner against this deal, it seems hard to believe there will be some magical diplomatic solution that allows him to both spurn the deal and leave it in place,” said Rosenberg.

What to tell Trump?

Given Trump’s deep-seated animus against the Iran deal — his predecessor’s signature foreign policy achievement — how much can Merkel and Macron realistically do to try to convince Trump to remain in the agreement?

Their influence is limited, argue the former US officials. Their suggestion would be to try to establish a warm personal relationship with the president and to be prepared with an offer that could encourage him to stick to the agreement.

But ultimately, said former US IAEA ambassador Holgate, Merkel and Macron should try to explain why it is in Washington’s own interest not to kill the deal.

“The only thing I can think of is to really bring home what the day after a broken agreement looks like. How can that possibly be in the US’s interest to have our European alliance in tatters, to have Iran unconstrained and perhaps more motivated than they have ever been in the last 15 years, to actually feel like they need a nuclear weapon to defend themselves against some future US action. I just can’t conceive of a way how the world without the JCPOA is in the US’ interest.”