Cairo Climate Talks held its 15th panel discussion on Wednesday night, focusing on how Egypt should address the consequences of climate change, particularly in regards to poor urban populations and those living in informal housing.

The inconvenient truth is that approximately 60 percent of Egyptians live in informal and unregistered housing without proper sewage and drainage facilities. This population — which represents the majority of the nation — is at the highest risk to suffer from the adverse effects of global warming.

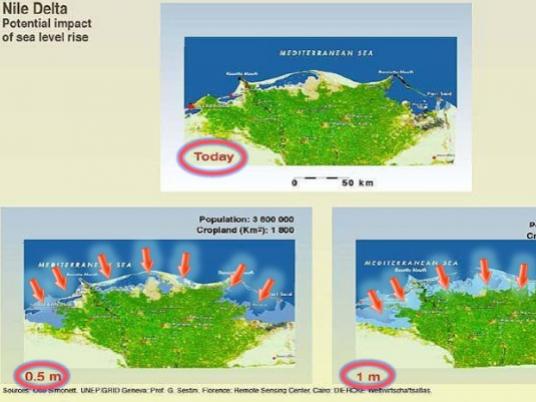

For instance, as climate change has caused sea levels to rise, flooding occurs, particularly in the Delta region, which has already prompted many residents to elevate their houses several feet off of the ground as a quick fix to the problem.

The altered water salinity levels that are brought on by climate change, as another example, are detrimental to agriculture and food security in a country where water is already scarce. For these issues, there are as of yet no real solutions, or even any quick fixes.

Wednesday’s discussion was called “Getting Ready,” as it was intended to be a first step in publically acknowledging and discussing the issues with all stakeholders — the public sector, research institutions, international organizations and civil society institutions — in order to create a framework for dealing with these issues.

As Saber Osman, a panelist from the Egyptian Environmental Affairs Agency (EEAA) — an agency under the umbrella of the Ministry of Environmental Affairs — humbly admitted on Wednesday night, “there currently is [no framework], and that is why I am here.”

The discussion between these stakeholders comes in light of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) latest assessment on global warming, which concludes that most of the MENA region — particularly Egypt — is highly vulnerable to the impact of climate change. Additionally, last week, Agriculture Minister Salah Abdel Momen announced that global warming is forcing the country to change its agricultural practices.

Even acknowledging these serious environmental hazards is somewhat of a breakthrough for the government, because, as Osman reiterated many times on Wednesday, “For 30 years we have had a regime that was pretending to address these issues while sitting at their desks. Now that we [the new government] have been handed these very large-scale problems, we are attempting to build bridges and learn from people who have been already working on it for years.”

Flying in from the UK to participate on the panel was David Dodman, a senior policy researcher at the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED), who opened up the discussion with a brief presentation highlighting what he considers to be the most critical environmental issues facing a country like Egypt, and what solutions they may require. Dodman has international experience tackling similar concerns in developing countries such as the Philippines and the Dominican Republic.

He briefly summarized the major issues in developing countries as: Rapid urbanization in low and middle income communities; very little to no association between the industries who cause climate change and those who are affected by it on the peripheries; how those most at risk are the ones least empowered to address the underlying causes; and the huge challenges to fight this problem for a politically turbulent and cash-strapped country like Egypt.

Dodman emphasized the importance of Community Based Adaptation (CBA), which involves doing extensive research, bridge building between various stakeholders, and determining “what exactly is a high risk area, and what determines when and how third parties should intervene.”

As Osman stated, “We are now aiming to focus on high risk areas and develop solutions.” However, when asked how they determined a high risk area, Osman admitted that he did not know.

Dodman’s concern was that a top-down approach of actively intervening without giving voice to various communities could be quite detrimental. He stressed that Egypt now has a major issue of trust between the government and poor urban communities, and hence the government must strive to rebuild that trust.

The panel was not focused on offering concrete plans of action, but rather highlighting the current problems. Regina Kipper, another panelist who has been working on CBA-related solutions in Egypt for a few years, stated that they are still working hard to develop a framework in which to highlight these issues, and that significant progress has been made in the field following the 25 January revolution.

Sarah Rifaat, 350.org’s Arab world coordinator, added that initiatives such as rooftop gardening, though small-scale, have the potential to tackle issues revolving around food security and access to arable land.

It was clear throughout the discussion that Egypt’s biggest hurdle right now is finding holistic approaches and big picture solutions, which all panelists admitted is next to impossible to push for right now given the political climate. However, what was impressive from Wednesday’s talk, and speaking to Osman following the discussion, is the government’s seemingly newfound commitment to transparency regarding climate change, and how willing they appear to be to listen to solutions.

Hearing public sector representatives answer many of my questions with a simple “I don’t know, but I would like to figure it out too,” was already a breath of fresh air compared to previous encounters with governing bodies who downright ignored that the issue exists.

A good start for Egypt, but there is a very long way to go, and the detrimental consequences of climate change are now to be expected, not just anticipated.