Contemporary art in Egypt is often framed in social and political terms, but at the Alexandria Contemporary Arts Forum, director Bassam El Baroni is engaged with a very different type of contemporary art discourse.

For the past few years, this nonprofit exhibition space founded in 2005 has been a home base of sorts for the kinds of art making and curatorial practice that international critics have dubbed the "educational turn": primarily discursive, highly theoretical and often pedagogical in its aims. "Fifteen Ways to Leave Badiou," an artist book produced last November, is one of the most recent manifestations of ACAF's very particular curatorial voice; unfortunately, this project's actual relevance for (or impact on) local arts practitioners is doubtful.

Both the premise of the book and its materiality as an object are promising. The publication starts off with a list: namely, radical leftist philosopher Alain Badiou's "Fifteen Theses for Contemporary Art," as well as a copy of the lecture Badiou gave on the theses in 2003. Next, Goldsmiths lecturer Suhail Malik responds to Badiou's proposition with an essay of his own; and finally, 15 artists from Egypt and the broader region take turns responding to each of the theses. The slim volume, with a flimsy cardstock cover and lightweight, colored copy paper, has a comfortable, homemade appeal that makes its often-difficult contents feel more accessible.

The choice of Badiou's text as a point of departure is timely, given the writer's ideological stake in the Arab Spring. Last spring, the Rabat-born, Paris-based philosopher wrote triumphantly in Le Monde of the uprisings in Tunisia and Egypt as potentially bearing the seeds of a utopian new world order. In light of these events, his 15 theses are interesting to consider as a potential system for the radicalization of art practice.

True to his militant, Maoist roots, Badiou claims that all contemporary politics, thought systems and art forms are, inescapably, manifestations of "Empire," his word for late neoliberal capitalism. However, a certain type of art — that is, an art that is "pure in form" and detached from the artist-as-personality and other market mechanisms — holds a potential to create systematic change by miraculously exposing us to "pure," universal ideas.

The essay by Suhail Malik that follows is a lively and engaging read that deconstructs Badiou's main points and lays out their flaws (the obvious one being that if everything is subject to the machinations of Empire, Badiou's own essay must be, too). It's a stimulating, if drily academic, dialogue.

After finishing the essays, the reader encounters the 15 works that were created in response to each of the theses. The curatorial choice in the selection of the artists is conceptually intriguing. One of Badiou's main arguments in his 2003 lecture is against contemporary art that is rooted in multiculturalism, identity politics or specific socio-political events, in favor of the universal and non-specific. By inviting only regional artists to participate in his project (but not commenting on this choice), Baroni offers a subtle reply to Badiou's demand.

Where the project really starts to become problematic, however, is in the framing of the works, which sets up impossibly high stakes. "Each artist was asked to develop an artwork in response to one specific thesis that was pre-selected based on conjectured relevance to the artist’s work," writes Baroni. "The resulting publication brings to light the cross-struggles between hegemonic orders, art, philosophy and universality." Unfortunately (or, perhaps, inevitably), the book falls far short of Baroni's aims.

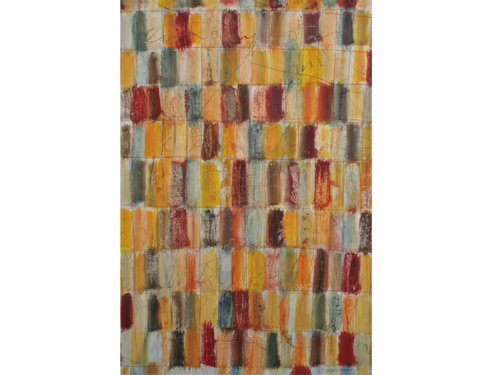

The strongest works are those that were themselves readerly, or at least seemed to deliberately engage with this particular mode of representation. Hassan Khan's "The Knot," for instance, self-referentially engages with Badiou and the materiality of the book itself. "The Knot" is an elegant response to Badiou's sixth thesis: "The subject of an artistic truth is the set of the works which compose it" — the cornerstone of Badiou's argument for a highly formalist understanding of art divorced from biography or artist's intention, which he considers to be mere accessories of late capitalism. Khan had the book's designer, Jurg Waidlich, create a knot image based on one taken from a 1970 text by psychiatrist R.D. Laing — a symbol meant to represent the interfolding relationship between self and other, subject and object, illustrating how perception is always filtered through a highly subjective lens.

Doa Aly's "On the Plurality of Consciousnesses," presented in response to thesis four, is similarly engaging. The piece is a cheeky answer to Badiou's argument against an art practice that attempts to encompass all forms (such as multimedia installations that include time-based media, sculpture, photographs and so forth) — the philosopher prefers "pure," unadulterated art forms. Aly responds with a text piece that presents a portrait of split and fractured psyches, presenting passages from a variety of texts on madness (usually female) authored by canonical, Western male authors, from Sir James Frazier to C.G. Jung, uniting them all in one, universalizing narrative.

Another intriguing, text-driven response is Mohamed Allam's piece, "We should become the pitiless censors of ourselves," which takes its title from thesis 14. Allam presents a fictional conversation between himself and Badiou, in which the philosopher disavows his statement in a somewhat cryptic, obscure series of Facebook messages. Interestingly, Allam's work and an open letter by STANCE/Cultural Monitoring Group were the only works included that openly alluded to the current political situation in Egypt.

But less successful pieces are in the majority, like Adel El Siwi's "Esam Mahrous and The Fortune Teller," a reproduction of two paintings from 2009 that falls completely flat in this mode of presentation and feels out of context in this very language-driven, conceptual framework. In general, the works that are presented in reproduction and weren't specifically created for the book tend to be underwhelming, like Akram Zaatari's "Twenty-Eight Nights and a Poem" — an index of the objects found in the photography studio of Hashem el-Madani, and part of a larger project sponsored by the Arab Image Foundation. The condensed format of the book doesn't provide a suitably rich platform for engagement with Zaatari's project, on the one hand, and the project itself seems to be lacking in relevance vis-à-vis the larger themes running through Badiou's text.

Part of the problem with engaging with these works is also the prompt-response arrangement; each thesis is printed on a blank page, followed by one artist's work and a few explanatory notes on the piece. The art would have been more engaging if it hadn't been subservient to the text.

Ostensibly, one of the goals behind presenting this project in a book format was a wider dissemination of ideas than an exhibition would have offered, but unfortunately, distribution of "Fifteen Ways to Leave Badiou" has been limited due to the ongoing political instability. The Cairo launch event, due to take place on 23 November, was canceled; the launch included lecturers and discussions that would conceivably have instigated a more impactful, longer-lasting discussion.

But even if extenuating circumstances hadn't hampered the release of "Fifteen Ways," its potential impact is still doubtful. It's a book that is rooted in timely and urgent questions regarding the political potential for art and our collective ability to challenge entrenched systems — but the execution of the project is too pedantic and too hermetic to allow the book to meaningfully engage with these issues. In the end, it fails to deliver on its over-optimistic promise.