Britain on Monday starts hearing Washington’s extradition request for WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange in a test case of media freedoms in the digital age and the limits of US justice.

A ruling against Assange in the case could see the 48-year-old Australian jailed for 175 years if convicted on all 17 US Espionage Act charges and one count of computer hacking he faces.

Each stems from his site’s release in 2010 of a trove of classified State Department and Pentagon files detailing the realities of the US campaigns in Afghanistan and Iraq.

One video from 2007 showed an Apache helicopter attack in which US soldiers gunned down two Reuters reporters and nine Iraqi civilians in broad daylight in Baghdad.

The files also disclosed the secret identities of diplomats and government agents in hostile environments — as well as locals who risked their lives by cooperating with the United States.

These names were redacted by the Western newspapers with which WikiLeaks initially worked.

But a falling out with their editors prompted Assange to release hundreds of thousands of files in their original form.

The US Justice Department said last May that the “human resources” compromised by Assange “included local Afghans and Iraqis, journalists, religious leaders, human rights advocates, and political dissidents from repressive regimes”.

His supporters argue that Assange’s prosecution was political — and personal — from the start.

“For the sake of press freedom, Julian Assange must be defended,” the Committee to Protect Journalists said in December.

– Trump involvement –

The case was injected with still more intrigue when the defense claimed US President Donald Trump promised to issue a pardon if Assange denied Russia leaked the emails of his 2016 election rival’s campaign.

“In August 2017, Donald Trump’s administration tried to pressure Julian Assange into saying things that would be favorable to President Trump himself,” Assange’s defense team coordinator Baltasar Garzon said on Thursday.

“When Julian Assange refused, he was charged and an extradition request was issued alongside an international arrest warrant.”

The White House called the allegation “another never-ending hoax and total lie” but a judge agreed to add it to the case file.

Assange is additionally shadowed by a rape allegation and a sexual assault claim that stem from his 2010 visit to Sweden.

He denied everything and called the case a legal pretext for Sweden to extradite him to the United States.

Assange agreed to attend hearings into the charges in London and his legal battles crossed borders yet again.

– International fugitive –

A UK court ruled in February 2011 that Assange could be extradited back to Sweden to stand trial.

He secured political asylum in Ecuador’s London embassy instead and became international fugitive by breaching his UK bail conditions in 2012.

Yet his campaigning continued in full.

Assange struck a deal with Russia’s state broadcaster RT in 2012 and began airing Skype interviews with anti-Western figures such as Hezbollah chief Hassan Nasrallah that further infuriated Washington.

A political realignment in Ecuador toward the United States saw Assange fall out of favor and begin losing his embassy privileges in 2018.

The last protections were lifted last April and Assange was dragged kicking and screaming out of the embassy and locked up in a high-security prison next to London’s Woolwich Crown Court where the case will be heard in two sessions this week and in May.

– Public interest –

The sex charges no longer apply because of the statute of limitations and Swedish investigators’ inability to question Assange about what a top prosecutor lamented in November remained a “credible” claim.

But the court will consider whether “the conduct described (by the US Justice Department) amounts to an extradition offense”.

Britain’s Crown Prosecution Service says the court must also weigh whether “extradition would be disproportionate or would be incompatible with the requested person’s human rights”.

The defense claims that it would and some US legal experts think Assange has a case.

“Use of the Espionage Act has a very checkered history in the century since Congress passed it,” University of Richmond law professor Carl Tobias told AFP.

Many think “extradition and US prosecution would have a chilling effect on press efforts to expose government information that is important to the public interest.”

Britain on Monday starts hearing Washington’s extradition request for WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange in a test case of media freedoms in the digital age and the limits of US justice.

A ruling against Assange in the case could see the 48-year-old Australian jailed for 175 years if convicted on all 17 US Espionage Act charges and one count of computer hacking he faces.

Each stems from his site’s release in 2010 of a trove of classified State Department and Pentagon files detailing the realities of the US campaigns in Afghanistan and Iraq.

One video from 2007 showed an Apache helicopter attack in which US soldiers gunned down two Reuters reporters and nine Iraqi civilians in broad daylight in Baghdad.

The files also disclosed the secret identities of diplomats and government agents in hostile environments — as well as locals who risked their lives by cooperating with the United States.

These names were redacted by the Western newspapers with which WikiLeaks initially worked.

But a falling out with their editors prompted Assange to release hundreds of thousands of files in their original form.

The US Justice Department said last May that the “human resources” compromised by Assange “included local Afghans and Iraqis, journalists, religious leaders, human rights advocates, and political dissidents from repressive regimes”.

His supporters argue that Assange’s prosecution was political — and personal — from the start.

“For the sake of press freedom, Julian Assange must be defended,” the Committee to Protect Journalists said in December.

– Trump involvement –

The case was injected with still more intrigue when the defence claimed US President Donald Trump promised to issue a pardon if Assange denied Russia leaked the emails of his 2016 election rival’s campaign.

“In August 2017, Donald Trump’s administration tried to pressure Julian Assange into saying things that would be favorable to President Trump himself,” Assange’s defence team coordinator Baltasar Garzon said on Thursday.

“When Julian Assange refused, he was charged and an extradition request was issued alongside an international arrest warrant.”

The White House called the allegation “another never-ending hoax and total lie” but a judge agreed to add it to the case file.

Assange is additionally shadowed by a rape allegation and a sexual assault claim that stem from his 2010 visit to Sweden.

He denied everything and called the case a legal pretext for Sweden to extradite him to the United States.

Assange agreed to attend hearings into the charges in London and his legal battles crossed borders yet again.

– International fugitive –

A UK court ruled in February 2011 that Assange could be extradited back to Sweden to stand trial.

He secured political asylum in Ecuador’s London embassy instead and became international fugitive by breaching his UK bail conditions in 2012.

Yet his campaigning continued in full.

Assange struck a deal with Russia’s state broadcaster RT in 2012 and began airing Skype interviews with anti-Western figures such as Hezbollah chief Hassan Nasrallah that further infuriated Washington.

A political realignment in Ecuador toward the United States saw Assange fall out of favor and begin losing his embassy privileges in 2018.

The last protections were lifted last April and Assange was dragged kicking and screaming out of the embassy and locked up in a high-security prison next to London’s Woolwich Crown Court where the case will be heard in two sessions this week and in May.

– Public interest –

The sex charges no longer apply because of the statute of limitations and Swedish investigators’ inability to question Assange about what a top prosecutor lamented in November remained a “credible” claim.

But the court will consider whether “the conduct described (by the US Justice Department) amounts to an extradition offense”.

Britain’s Crown Prosecution Service says the court must also weigh whether “extradition would be disproportionate or would be incompatible with the requested person’s human rights”.

The defense claims that it would and some US legal experts think Assange has a case.

“Use of the Espionage Act has a very checkered history in the century since Congress passed it,” University of Richmond law professor Carl Tobias told AFP.

Many think “extradition and US prosecution would have a chilling effect on press efforts to expose government information that is important to the public interest.”

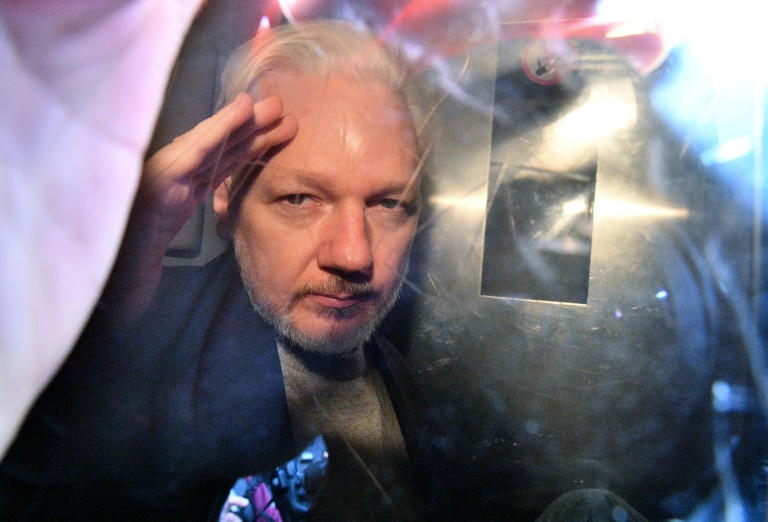

Image: AFP/File / Daniel LEAL-OLIVAS Assange’s supporters argue that his prosecution was political — and personal — from the start