One might feel uneasy after reading Egypt and Egyptians in the Mubarak Era, the newly published book by prominent Egyptian scholar Galal Amin.

The selection of pre-revolutionary articles gives critical accounts of economic, social, political and cultural crises brought about by ousted President Mubarak’s policies. With a new preface, entitled “Egypt surprises itself” in reference to the revolution, Amin attempts to trace “important developments that took place in Egyptian society,” pushing people to revolt. His answers to the recurring question, “What brought about the revolution?” are, however, in many cases simplistic, vague or non-factual.

Current debates in Egypt mostly attribute chronic socio-cultural and economic problems to Mubarak’s three-decade autocratic rule. Amin seems to subscribe to this understanding, but many of the problems he addresses in Egypt and Egyptians in the Mubarak Era, such as the negative effects of economic liberalization and rise of social conservatism, are not Mubarak’s sole responsibility.

Both former presidents, Gamal Abdel Nasser (1952-1970) and Anwar Sadat (1970-1981), are responsible for certain problems that Mubarak inherited. But in Amin’s book, Mubarak receives all the blame.

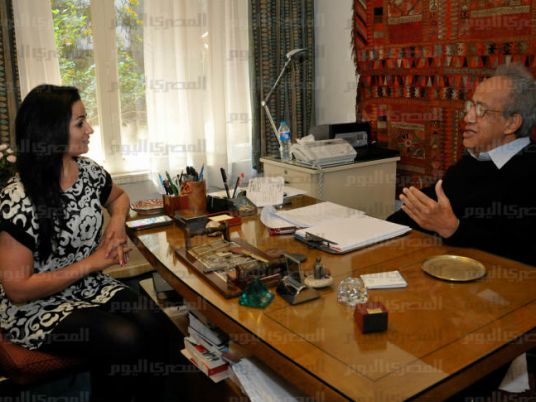

An economics professor at the American University in Cairo, Amin is famous for his critical writings on Mubarak’s domestic and foreign policies. He is also an intellectual who regularly engages in religious and cultural debates.

In Egypt and Egyptians in the Mubarak Era, Amin uses the “soft state” theory developed by Swedish Nobel Laureate economist Gunnar Myrdal to explain the 25 January revolution. A “soft state” is one that’s unwilling to perform its main functions – namely preserving law and order – leaving mediocrity and lawlessness to prevail. According to Myrdal in his seminal 1968 book, Asian Drama, there’s no respect for the law in such a state, and breaking legal codes is the cultural norm.

Amin allocated his first chapter to this concept, touching upon the deterioration of the education and health systems, among other symptoms of the so-called soft state under Mubarak.

The most outstanding application of the theory to Egypt is an article by renowned Middle East expert John Waterbury published in the mid-1980s. In The “Soft State” and the Open Door: Egypt’s Experience with Economic Liberalization, 1974-1984, Waterbury argues that Egypt experienced symptoms of the "Soft State" under the Nasser regime, since he didn’t allow any kind of autonomous growth.

Amin, however, argues that Egypt started turning soft, so to speak, only under Sadat’s rule.

The book is rife with contradictions and arbitrary judgments, probably because the articles were written on different occasions and have no common thread.

For example, it is widely agreed that Egypt's top Sunni institution, Al-Azhar, has been losing its influence over the past century. Amin, on the other hand, argues that Al-Azhar’s major problem is that its clerics supported Mubarak. This argument might be true, but what surprised many was the significant participation of Al-Azhar imams in the revolution.

Amin’s popular book has a strong nostalgic tone.

In Egypt and Egyptians in the Mubarak Era, the same nostalgia Amin used in his popular book Whatever Happened to the Egyptians? dominates the text, although there have been some improvements in cultural and political conditions over the past few decades.

One case in point is the development of journalism and news media. Amin portrays a gloomy media landscape, with what he says is significant deterioration of both state-run and privately-owned newspapers. He argues that newspapers lost their great writers between the 1950s and 1980s.

This arbitrary judgment overlooks significant developments in Egyptian media, one of which is that journalists’ struggle made it possible to criticize the Egyptian president for the first time in the country's history under Mubarak. Starting in 2005, several private papers were established and continuously pushed boundaries by highlighting corruption and problems related to Mubarak’s policies.