There is little belief inside the American government that Biden’s actions will completely shut down the constellation of Iranian proxy groups that have been responsible for escalating attacks on American bases and commercial shipping lanes in the Red Sea. A longer-term solution remains elusive, as Biden enters a reelection year while also pursuing a broad diplomatic breakthrough he hopes could transform the larger region.

Whether the 125 precision-guided missiles fired over 30 minutes Friday night will have the effect of preventing further attacks on Americans is a question officials aren’t yet ready to answer.

But there is hope that by taking out intelligence centers, weapons facilities, command and control operations and bunkers used by Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps Quds Force and other affiliated militia groups, the US can diminish the militants’ capabilities and send a message that attacks won’t go unanswered.

“I think it is a real strong deterrence,” said Sen. Tammy Duckworth, an Illinois Democrat and Iraq War veteran. “We’re saying: Listen, we don’t want to go to war. But have a little taste of what we can do. Here you go. Eighty-five targets. And I think that that is part of the balancing act that we need to be engaged in right now.”

The American reprisal is not over, and officials have not ruled out unseen elements, like cyberattacks, to degrade Iran and its proxies’ capabilities. The White House said clearly ahead of the counterstrikes that it expected a multiphase response, with a trajectory and duration likely to be dictated by circumstances on the ground.

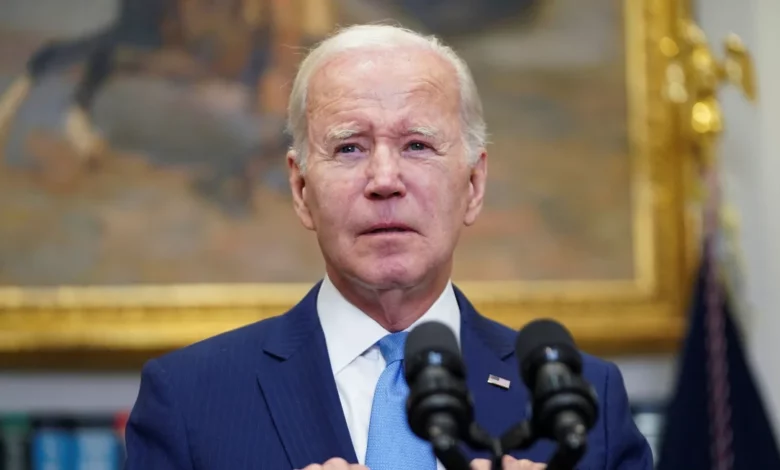

How the coming days unfold will have wide ramifications for the region and for the president himself, who spent the hours before the American B-1 bombers began hitting their targets consoling grieving families of the three Americans killed in Jordan.

It was only about an hour after Biden departed Dover Air Force Base in Delaware that the first US strikes began in Iraq and Syria. The timing was coincidental, officials said, but nonetheless symbolic of the gravity of his decision.

“Our response began today. It will continue at times and places of our choosing,” Biden said in a written statement. “The United States does not seek conflict in the Middle East or anywhere else in the world. But let all those who might seek to do us harm know this: If you harm an American, we will respond.”

In selecting how to respond to the death of three Americans, Biden faced a consequential choice: how to retaliate, and send a message to Iran, while avoiding getting pulled into a wider regional war.

Inside the Situation Room, Biden and his team assessed a set of options that each came with a certain degree of risk. Strike too hard, and what had been a relatively low-grade exchange of fire between the US and Iranian proxy groups could expand into something far more serious. Strike not hard enough, and a message of impunity could be interpreted by the group behind the deadly drone attack — and by Americans at home.

Adding another layer of complexity were the difficult negotiations ongoing to secure the release of hostages held in Gaza and impose a prolonged pause in the fighting there, talks which officials said Biden was loathe to disrupt by potentially escalatory action.

“It’s both a science and an art,” said former Defense Secretary Mark Esper, who engaged in similar Situation Room debates during his tenure in Donald Trump’s administration. In developing options for the president, officials weighed the complexity of the attack, the estimated damage it would do, the number of Iranians or militia members it could kill, and the potential retaliation it might prompt.

“That’s a discussion that goes on within the room: what will the impact be? What will we expect from the Iranians?” Esper said. “It’ll be important to see what happens when the sun comes up tomorrow morning in Iraq and Syria.”

What Biden and his advisers agreed on was that the US response to the Americans’ deaths would have to be on a correspondingly different scale than the tit-for-tat exchange of fire that had been unfolding in the region since October 7.

They were not short of options: plans have long been drawn up to go after targets associated with the array of Iranian-backed groups that have been fomenting instability in the region. Identifying a calibrated approach did not take long. Biden told reporters on Tuesday he’d made a decision on how to counter the drone attack — only two days after he vowed in South Carolina: “We shall respond.”

Bad weather in the region played the biggest role in dictating when the strikes would occur, officials said afterward. Clear skies on Friday meant a lower risk of striking unintended targets — and preventing civilian casualties.

The question that can only be answered in the coming days and weeks is whether the response will move the needle in Iran, who the US has accused of supplying and resourcing the militant groups behind the attack that killed the three Americans.

American officials had already been detecting signs that leaders in Tehran were growing nervous about some of the actions of its proxy groups in Iraq, Syria and Yemen, according to multiple people familiar with US intelligence. And there are clear indications that Iran isn’t looking for a war with the United States — just as Washington insists it isn’t seeking a broader conflict.

But how to resolve the problem of the militias is still not an easy one. There has been little evidence that American military action against them over the past several months — which the US frames as an effort at deterrence — has actually deterred anything. Biden acknowledged as much last month, saying that American strikes in Yemen on the Houthi rebel group haven’t stopped their attacks on the Red Sea shipping lane.

Despite calls from Republicans in Washington to go directly after sites inside Iran, that option appeared unlikely from the start as the White House seeks to avoid becoming embroiled in a full-blown war.

And there are few outward signs Washington is attempting to renew any diplomatic engagement with Tehran after Biden’s attempts earlier in his term to resuscitate the Obama-era nuclear deal stalled out. “There’s been no communications with Iran since the attack that killed our three soldiers in Jordan,” National Security Council spokesman John Kirby said Friday night.

That makes for a vanishingly narrow path for the president to navigate.

“This is a very fine line. They are threading a needle here. And some of this is informed by history,” said Beth Sanner, a former senior intelligence official who was Trump’s intelligence briefer in the tense days surrounding his decision to strike a top Iranian general, Qasem Soleimani.

“This is what every administration does,” Sanner said. “You are trying to figure out where that line is. … There isn’t a thing that you can point to that is the dot. You’re going to have to feel your way around it.”