Most of Iraq’s celebrated authors live and write outside their country: Fadhil al-Azzawi is in Berlin; Sinan Antoon is in New York City; Inaam Kachachi is in Paris; Mahmoud Saeed is in Chicago; Hassan Blasim is in Finland; Ali Bader is in Belgium.

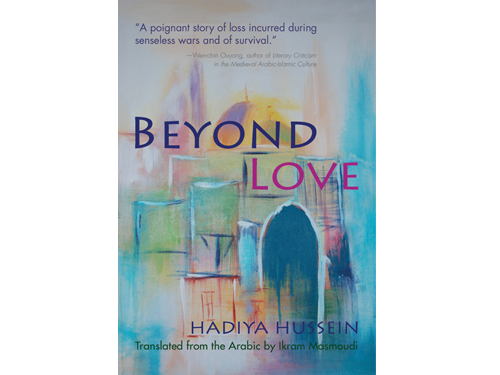

Hadiya Hussein, whose third novel, “Ma Ba’d al-Hub” (2004), was just published as “Beyond Love” by Syracuse University Press, left for Jordan in the 1990s. At present, she lives in Canada.

Hussein, like the other Iraqi authors scattered around the world, must draw and re-draw Iraq from memory. Near the beginning of “Beyond Love,” a character complains that memory “reshapes the past like an enemy lying in ambush.”

Indeed, the novel has a complex relationship with memory and history. Huda, the book’s protagonist, both preserves and flees her past. She clings to the stories of people who struggled against the Saddam Hussein regime, but she also wants to forget them and start anew.

Characters in “Beyond Love” — they are mostly women, men having died or disappeared — find memories of their home country painful. Yet these shifting memories are also irresistible. As one character says, “we’re eager to torture ourselves and whip our souls” with recollections “for reasons we don’t understand.”

The novel’s foreground action is set in Jordan, just after the First Gulf War in 1991. That’s when Iraq’s sudden and crushing defeat sparked both an anti-regime uprising in the south as well as severe crackdowns from the state. In the years that followed, many Iraqis were forced to, or chose to, flee the country.

Here, Jordan is an in-between space: The protagonist is caught between an Iraqi past that she cannot digest and a future in exile that she cannot imagine. Of the three central characters, only one — Huda — is fully present. The second is Huda’s dead friend, Nadia, and the third is Nadia’s lost lover. Huda’s daily life in Jordan is not without possibilities, but these are overwhelmed by the dead, the missing and the unknown.

Hussein’s structural choices — prioritizing background over foreground, memory over action — could easily bog down the narrative and frustrate the reader. However, the lure of the characters’ pasts keeps the reader moving. The book begins as Huda recalls working with Nadia at the ironically named al-Amal (Hope) underwear factory, a job where “floating flannel particles clung to our clothes and our eyelashes, dulling the shine in our eyes.” Throughout the book, language is beautifully and vividly rendered by translator Ikram Masmoudi.

The reader, like Nadia and Huda, is drawn to the flame of memories. Huda flees the consequences of voting “no” in an Iraqi “election.” Nadia flees multiple horrors and losses; she is seeking asylum when she is killed in a traffic accident. Before she dies, she tells Huda, “… every time I want to get away from these tragedies, I get drawn back to them.” It is the same for the reader.

Nadia, like Huda, is nearly drowned in her memories. Indeed, Nadia’s recollections seem to smother her: “The past that we buried has left us with no present through which to reach another life.”

And yet both Nadia and Huda, like many other Iraqi refugees in Jordan, still reach toward another life. Huda’s personal memories, Nadia’s journal and Nadia’s love letters are central to the story. Yet Huda still struggles, inexorably, to move toward a new beginning. She spends her weekends at the confusing and bureaucratic refugee office, petitioning for futures she is not sure she wants.

The three non-loves

As she waits, Huda stumbles into two men who might have loved her. A third man, her betrothed, perhaps should have loved her. One non-lover is a worthy Jordanian: He is a talented musician who loves poetry and treats Huda with affection and sympathy. He is also blind, but it is Huda who cannot see. She barely recognizes his love and barely notes his suppressed tears when she tells him she is leaving.

The second non-lover is a mysterious Iraqi who, like Huda, is in Amman seeking asylum. He has already been accepted by Australia; after briefly knowing Huda, he offers to marry her and take her along. She cannot make up her mind about his proposal. Her indecision is compelling, but the “aha” at the end of this story is the novel’s one false note.

Meanwhile, Huda’s third non-love is a more conventional relationship with her fiancé and cousin, Youssef. This relationship ends when Youssef says he will not join Huda in exile. He writes from Baghdad: “Memories can no longer rekindle our passion when its flame dies. Memories have become a toy we use to flirt with the present out of fear of the future…”

Youssef wants to shed the past, including Huda, and move on. He wants a new Iraq, a real future, the fall of the regime. He passes along a verbal message that “… people are on the rim of a volcano. The regime will fall, and you will return.”

Here, memories hold the characters back, but they also push them forward. Huda encourages Nadia to remember, to bear witness. And it is through passing on Nadia’s memories that Huda achieves some small serenity. She finds a home for Nadia’s papers, and thus can travel more easily to America.

And yet this shedding of memory is not the last word, either. As Huda heads toward her plane, she leaves the reader with two lines from Iraqi poet Ibrahim al-Zabidi: “Oh, morning of Baghdad, Farewell/I’m entering exile.”

Huda has moved “beyond” love, and yet love still guides her decisions. Just so, she moves to a space beyond memory, and yet this image — “Oh, morning of Baghdad” — cannot be escaped.

This piece was originally published in Egypt Independent's weekly print edition.