Mohamed was going to the Heliopolis Sporting Club on April 25th, a day that coincided with the second wave of protests against the transfer of two disputed Red Sea islands to Saudi Arabia, when police stopped him and demanded his phone.

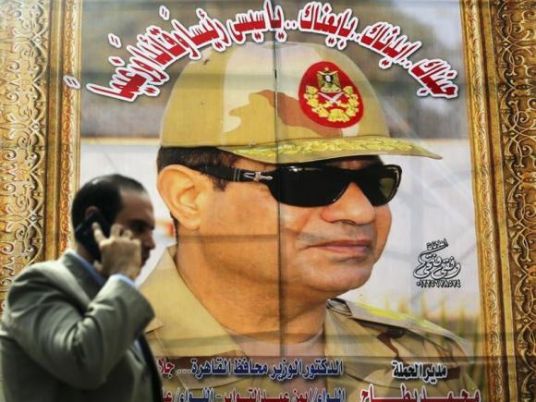

Comical photographs of Egyptian President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, dressed as a superhero, adorned with flowers, and given the wings of an angel, saved Mohamed, who preferred not to use his real name, from arrest that day.

Located in the upscale Cairo neighbourhood of Heliopolis, the club is very close to Mohamed's home. "I walk there all the time," he told Aswat Masriya. Mohamed planned to spend the day with his friend, far from the protests taking place in Giza. He waited for his friend in front of a nearby mosque so that they could walk there together.

"I hadn't even been waiting for five minutes," he said explaining how his short wait was interrupted by a man dressed in civilian clothing who "kept asking questions".

"I live here," Mohamed told the man.

"Show me your national ID card. Show me your mobile phone. What are you doing here? Who are you waiting for?" the policeman in plain clothes spurted orders and questions at Mohamed.

Confused by what he saw in Mohamed's phone, the low-ranking officer took Mohamed to another police officer, who was dressed in uniform and surrounded by "men wearing black."

The officer proceeded to look through Mohamed's photo gallery, even after Mohamed told him that there were some private photographs, "Then he saw all the photographs of Sisi."

A display of Sisi-mania, photographs of Sisi with hearts, angels and horses, super hero capes, red laser beams glowing out of his eyes surprised the officer scrolling through Mohamed's phone gallery.

"The day before, I had downloaded a lot of exaggerated photos from pages like 'for the love of Sisi' and stuff, it was all for humour," he explained to Aswat Masriya, "I was making fun of them."

Mohamed began to panic, "What's wrong? I am only going to the club."

"Why do you have all these photographs?"

"I am a fan of the president," Mohamed lied, the officer laughed, and thankfully, Mohamed managed not to get arrested.

Ragia Omran, one of the lawyers in the Front of Defence for Egyptian Protesters, told Aswat Masriya that "nothing in the law stipulates that they [the police] have the right to do that."

Usually, the people that the police inspect are "not caught red-handed, they are taken arbitrarily. There were no protests in downtown that day anyway," Omran said, referring to the arbitrary arrests that took place before and on April 25, when various political movements and parties announced they would protest "the sale of Egypt."

Demonstrations on April 15 and April 25 included chants against the police, the regime, military rule, and against Egypt's maritime border agreement stipulating that the Red Sea islands of Tiran and Sanafir fall within Saudi Arabia's territorial waters.

A campaign of mass arrests saw even wider securitization of public spaces, with security forces arresting scores of people, from cafes and from their homes, days before protests were due to take place. Freedom for the Brave, one of the groups that provides support for detainees, reported that over 300 were arrested, before and during April 25.

Activists and social media users, while frightened, still poked fun at the ongoing campaign of raids and detentions, joking, "Guys, please do not go home, or visit anybody, or be in the streets, or sit at a cafe."

Mohamed Youssef, the assistant interior minister for transportation police, told Aswat Masriya that he ordered security forces to widen the "circle of suspicion," which meant that security forces would tighten measures on buses, metro stations, and trains.

Security forces also took up the practice of stopping people and inspecting them arbitrarily. In fact, various social media users shared testimonies of police stopping microbuses and looking through the phones of the passengers. They also testified to seeing people being taken and not coming back, and to police interrupting their journeys to university campuses to poke around their belongings.

This intensifying police practice of rummaging through peoples' phones often harms pedestrians who are not politically affiliated. "Sometimes photos and posts just show up on people's Facebook pages," Omran said elaborating that people find themselves facing politicised charges on that basis alone.

In fact, the practice also puts those on the list of phone contacts, or a person's "Facebook friends", in danger as well.

Mohamed may have been able to get away with his Sisi fandom photographs, but he fears his name might have been listed with the police after another incident of police inspection of his friend's phone.

Mohamed's friend was also stopped by the Behooth metro station in Giza to get his phone searched by the police. Whilst going through Facebook, the police saw a post Mohamed had made, in which he commented on "the oppressive state." Police took note of his name. A case in point, Mohamed says.

When asked specifically about the practice, a security source denied that police look though citizens' phones or laptops, adding that private Facebook pages are not monitored and that there is no surveillance.

According to Amnesty International, Egypt's security apparatus has a history of monitoring electronic communications, while many activists “have also been arrested and prosecuted for content they have posted on social media.”