Many observers fear that the country may be transiting from one authoritarian regime to another under the rule of the Muslim Brotherhood. Some talk about Egypt turning into an illiberal democracy in which democracy exists only procedurally, with no liberties guaranteed.

Others warn against the rise of a disguised religious state where unelected clerics will dominate the state. All in all, there seems to be a consensus that, in the absence of a sizable pro-democracy movement, Egypt is likely to end up with some form of elected authoritarianism.

Brotherhood majorities in Parliament and the Constituent Assembly, and the election of a Brotherhood president, have all produced considerable fear among liberals that the group has strong authoritarian inclinations.

The Brotherhood has had a rather unfavorable position on rights and liberties. Their parliamentary bloc was not in favor of a new trade union law that would guarantee the freedom of organization of workers.

A few weeks after President Mohamed Morsy was sworn in, Brotherhood associates filed lawsuits against newspapers and other media channels accusing them of insulting the president.

Moreover, Morsy’s decisions to call the once-disbanded Parliament to reconvene and to remove the public prosecutor hardly showed his respect for the rule of law.

Over and above, the clashes with secular protesters by supporters of the Brotherhood made even more people concerned about the future of the freedom of public protest in Egypt.

However, the continuous attempts to restore the authoritarian order do not seem so far to have been that successful. Various sorts of protest still occupy the public sphere, the media still has enough freedom to level vehement criticism at Morsy and the ruling bloc, and most oppressive measures have backfired on the authorities.

Why has it been so hard to restore the old repressive regime by a newly elected and hence more legitimate Islamist majority? The answer lies in the social and economic changes that Egypt has witnessed in the last two decades and that contributed to the ouster of former President Hosni Mubarak.

End of Nasserism

To start with, the 25 January revolution was the final showdown for the Nasserist, paternalistic state that dominated the country for six decades. In such a setting, the state maintained its authoritarianism by giving away economic entitlements in return for political rights.

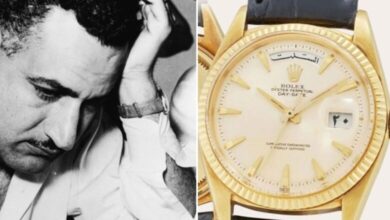

President Gamal Abdel Nasser enjoyed the support and loyalty of significant strata of middle-class employees and the formal unionized labor force, who were heavily dependent on the state.

Ever since the time of former President Anwar Sadat, this situation has been running out of money and against time. Most market entrants since the 1970s and 1980s either joined the emergent formal private sector or the informal sector. The state-dependent classes have grown more destitute as the neoliberal reforms of the 1990s took their toll on their real wages.

The far-reaching deregulation of significant sectors of the economy in the last decade created a new middle class that is more linked to the global economy and less dependent on the state. What’s new is that the traditional middle-class professionals who work predominantly for state-owned facilities are becoming vocal about their social and economic demands and thus less supportive for whoever is in power.

Egypt has witnessed its first post-revolution physicians’ open-ended strike, together with the emergence of an influential independent teachers’ union that could call for various forms of protests.

Bankrupt authoritarianism

The formula is very simple. The restoration of the authoritarian order, under an electoral guise, needs resources. The Brothers need to mobilize financial resources that could buy them the support of sizable strata.

This is not likely to happen anytime soon as the Brothers will have to adopt austerity measures to get out of the pressing fiscal crisis. These measures are expected to render them even less popular.

As a matter of fact, the government’s declaration in September that there is no money for any extra payments for protesting teachers and doctors is quite historic. For the first time in Egypt’s modern history, the state has declared its inability to sustain the very basis of its political authoritarianism by delivering side payments.

One can safely state that this is the actual and long-expected end of the Nasserist order.

Losing carrot and stick

Now the state has lost both its carrot and stick. The police force is a shambles and the state is on the verge of declaring bankruptcy. The only thing the ruling elites can offer is the distribution of political rights to the protesting masses, through which conflicting social interests can be represented and thus mediated and possibly mitigated.

No short-term solutions can be given, only longer-term ones that depend on the ability to hammer out a political system that can mediate social conflict. However, such an option only means that the newly formed political system is bound to be reshaped in a radical way, and that public policies are likely to transform so as to accommodate the interests of the newly represented groups.

Can the Brotherhood, with its current social composition and political choices, bear such a choice?

Amr Adly is director of the Social and Economic Justice Unit at the Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights. He has a PhD in political economy.

This piece was originally published in Egypt Independent's weekly print edition.