BAGHDAD (Reuters) — They survived censorship under Saddam Hussein and the years of violence that followed his downfall, so the booksellers of Baghdad are not too worried by coronavirus.

Iraqi authorities have urged people to avoid public gatherings and ordered cafes to close as virus cases have hit 67, mainly blamed on travelers from Iran.

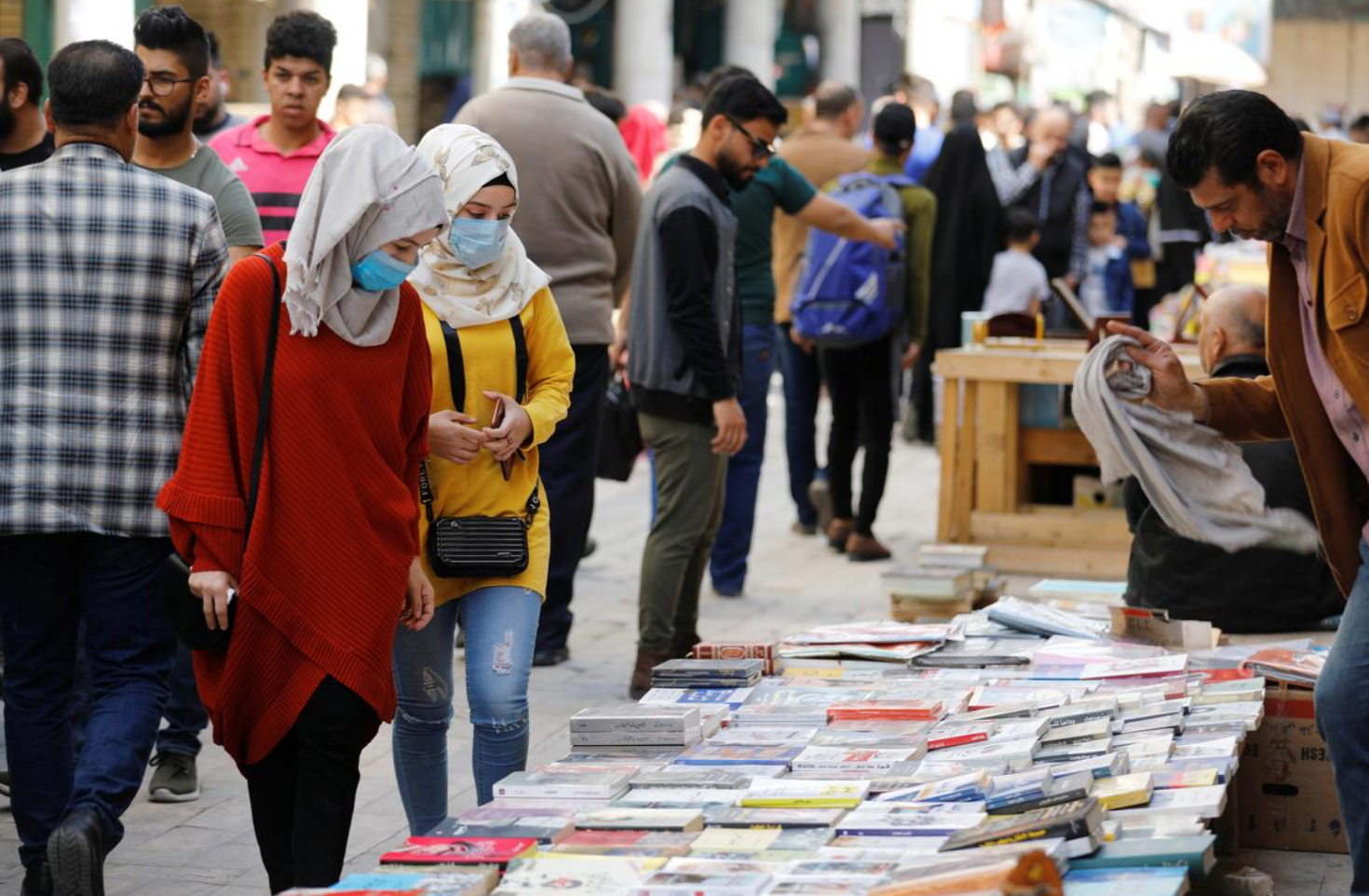

Yet the booksellers of Mutanabbi Street on the banks of the River Tigris are still meeting their customers to do business and discuss politics in the usual way.

Some cultural events have been canceled but writers, musicians and painters still flock there on Fridays, gathering near the imposing statue of Mutanabbi, the 10th century poet after whom the street is named.

Numbers are down due to the virus and months of violent anti-government street protests, but staying at home is not an option for hard-core book lovers, even if it does mean wearing a face mask.

“I have been coming here every Friday since the 80s when I was a student,” said Jawad al Bidhani, a university professor, who bought four academic books.

“The disease is dangerous and fatal. But this won’t prevent us coming to Mutanabbi Street. So we take the opportunity to sit here with our friends for an hour or two,” he said.

The market, where books are brought on trolleys from store-rooms in nearby buildings to be displayed on tables in the street, is a barometer of intellectual life.

The city’s literary tradition is summed up in the saying: “Cairo writes. Beirut prints. Baghdad reads.”

Choices were limited under Saddam, who banned anything critical. After he fell, political and religious literature was popular, but tastes are changing as Iraqis lose confidence in a political system many see as corrupt.

“There is little demand for political books, also not religious books,” said Hamza Abu Sara, a bookseller. “People buy more self-help books … to be positive, or fiction,” he said.

An economic crisis has hit sales, but Saraa al-Bayati, the book market’s only female trader, is not thinking of closing.

“We are doing kind of okay,” she said in the one-room shop where she sells her own publications and works in translation.

Her bookshop is her dream. Her family would not let her study journalism at university, deeming the job too dangerous in turbulent Iraq.

She graduated in engineering but decided to found a publishing house. “I simply love books,” she said.

Reporting by Ulf Laessing; Additional reporting by Maher Nazem and Khalid Al-Mousily; Editing by Giles Elgood