Egypt's asbestos factories were officially closed down in 2005, and yet the impact of this extremely dangerous material is being felt more vividly than ever today, because of the long timespan between the actual exposure to deadly asbestos fibers and the onset of asbestos-related cancers.

Studies conducted by both the National Cancer Institute and Abbasseya Hospital have revealed a rise of asbestos-related cancer patients in the past few years, a number that is expected to grow in the coming years.

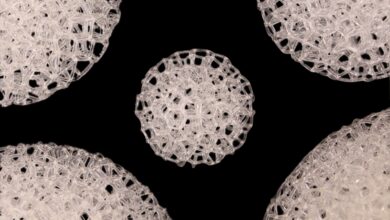

Asbestos is the name given to a group of minerals that occur naturally in the environment as bundles of fibers that can be separated into thin, durable threads. This material is extremely resistant to heat, fire and chemicals, and for these reasons has been widely used in many industries throughout the 20th century.

Asbestos is a generic name, and three different types of asbestos belong to this family: blue asbestos (crocidolite), yellow asbestos (amosite), and white asbestos (chrysotile). The first two are extremely dangerous for humans if inhaled, because the needle-like blue and yellow asbestos fibers can embed themselves in the lungs and cause cancers 20 to 30 years later.

“Chrysotile is less harmful because it is inert and has no chemical reaction with any part of the body,” explains Salah al-Haggar, chairman of the mechanical engineering department at the American University in Cairo, adding that the round shape of white asbestos fibers makes them harder to ingest or inhale.

Awareness of the dangers of asbestos developed much sooner in the West than in the developing world. Those companies working in asbestos responded to the negative impact of such awareness by aggressively marketing their wares in the developing world. In Egypt, all types of asbestos – even the deadly blue type – started being imported in 1944. Some industries used asbestos for insulation, roofing, fireproofing and sound absorption, while the cement industry used asbestos for its cement-strengthening properties. Soon, 14 cement factories located around Cairo started using asbestos in the manufacture of water pipes, and failed to introduce security measures – such as the wearing of a mask – to protect their workers.

Apart from the obvious threat to workers within the factories, the other main issue was the slack waste disposal methods used. Cement factories carelessly disposed of their waste, including piles of cement and rubble containing asbestos, in the vicinity of the plant, close to residential areas and schools.

Dr. Rabab Gaafar is a professor of medical oncology at the National Cancer Institute in Garden City. She has dealt with many patients suffering from asbestos-related cancer over the years and has written countless papers on the mesothelioma epidemic, a relatively rare cancer of the thin membranes that line the chest and abdomen, also caused by exposure to asbestos.

“No one knew at the time how dangerous asbestos was as a material, and it was put everywhere – in the buildings, in the garages, in the stop signs – and highly appreciated for its excellent isolation power,” she explains. Gaafar says that the phenomenon of asbestos-related cancers is rising in Egypt. “It takes 25 to 30 years on average to develop into a disease and become symptomatic. If a child inhales deeply in his lung an asbestos fiber, he can develop a cancer at the age of 30,” she says.

“The symptoms are the following: chest pain, dry cough, shortness of breath and tightness of the chest, all symptomatic of a lung cancer,” explains the doctor.

“This is unfortunately a very aggressive disease. We have done several trial treatments for these patients, ranging from radiotherapy to chemotherapy. … These heavy treatments have brought mild improvements, but there is no cure as such,” she stresses. The patients who cannot undergo surgery live less than a year on average. With surgery, their life expectancy can reach three to four years after diagnosis, according to the doctor.

Although blue asbestos was banned in Egypt in the '70s after its dangers were revealed, the government has not yet undertaken a nationwide campaign to remove it from buildings and the infrastructure in general. Haggar explains why: “Egypt is not famous for keeping up-to-date records, and no one really knows in which structures the blue asbestos was used.”

What is even more alarming is that asbestos fibers contained in a cement-asbestos mix begin to be released as buildings start deteriorating, causing those using or living in such buildings to inhale the fibers. Since many buildings in Egypt are in an advanced state of decay, and since maintenance of old buildings is a rarity, the danger is vivid.

According to a paper written by Abdel Hameed A. Awad, the head of the air pollution department at the Egyptian National Research Centre (NRC), any intake of asbestos, regardless of the quantity, can be fatal eventually. While running some air pollution tests close to the ORA-Egypt cement factory, located in Tenth of Ramadan City, he discovered that although the plant closed in 2005, traces of asbestos can still be found today.

The ORA-Egypt cement factory closed down in 2005 after sick workers held a long strike to denounce the lack of safety measures to protect them from the inhalation of asbestos fibers. The case finally ended up in parliament, which decided to close the factory and shut down all the asbestos departments of all the cement factories in Egypt.

But for the people living in the vicinity of these factories and the workers themselves, the damage was already done.

Mohamed Abdel Fatah is 47 years old. He grew up and lived for 38 years in Maasara, a neighborhood located south of Maadi, less than a kilometer away from a Sigwart cement company.

“When I was a child, I often played with some other kids from the neighborhood on the heaps of rubble discharged by Sigwart trucks in the streets,” he explains. “We had no idea this was dangerous, and the cement company did not bother disposing of its waste further away from the community and its residents."

A study conducted by Awad from the NRC has revealed that asbestos fibers can reach a 5km range around the factory in quantities much higher than what is safe to inhale.

“I was diagnosed with mesothelioma cancer seven months ago,” Abdel Fatah explains. “I went to the doctor for a checkup because I was feeling acute pains in the back and inside my body, and after taking an x-ray, the doctor discovered that I had a small bag of water in the chest, and I did an operation to drain the liquid out. Unfortunately, the water starting accumulating once more in my chest, so much that I started having trouble breathing.”

The doctor was immediately able to link Mohamed’s disease to his early exposure to asbestos.

Mohamed’s two brothers, his sister and his mother have all died of asbestos-related cancers over the past 10 years. He is now starting chemotherapy at the NCI, which offers free chemotherapy sessions. Looking determined, he explains that what deeply upsets him is not the prospect of dying, but that his disease is the result of negligence.

"Everyone dies; this is natural. What drives me crazy is that I am going to die because of a cement factory’s carelessness,” he says.

Since 2005, all cement industries have complied with the ban imposed on the import and manufacture of asbestos and have stopped using the material. Unfortunately, the legislation regarding asbestos has two major loopholes: it bans “asbestos” but the names of its subcategories (crocidolite, amosite and chrysotile) are not mentioned anywhere, making it possible for workshops to freely import blue, yellow and white asbestos under their scientific names without being challenged. These materials are then used in the production of insulation boards and fire-resistant clothing, among other things.

“Informal workshops still import raw asbestos under its other names and the authorities ignore the fact that these materials are types of asbestos,” Haggar says.

He adds that the legislation has another loophole. While the ban covers the import of raw asbestos, it does not restrict the import of manufactured products that contain asbestos, including certain kinds of glass. Such goods are, of course, ticking time bombs in their own right.