One of the less expected was that over a year into the conflict, President Xi Jinping of China would receive a courting from European leaders. Given the EU’s hard stance on Russia, you’d be forgiven for thinking they’d take a similarly firm approach with the Kremlin’s most important ally.

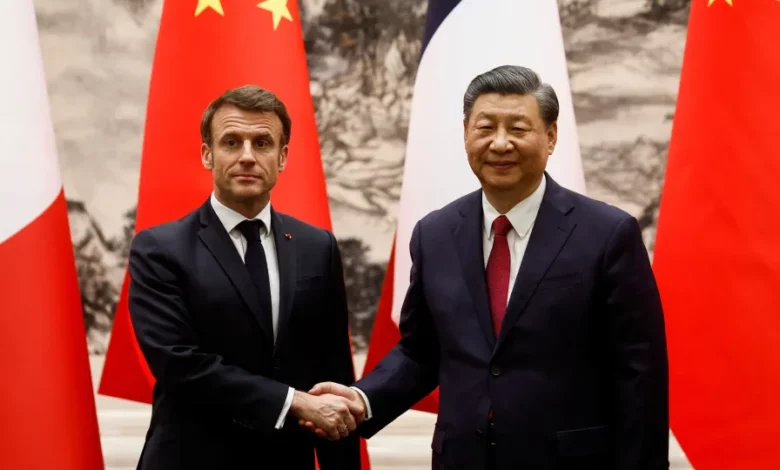

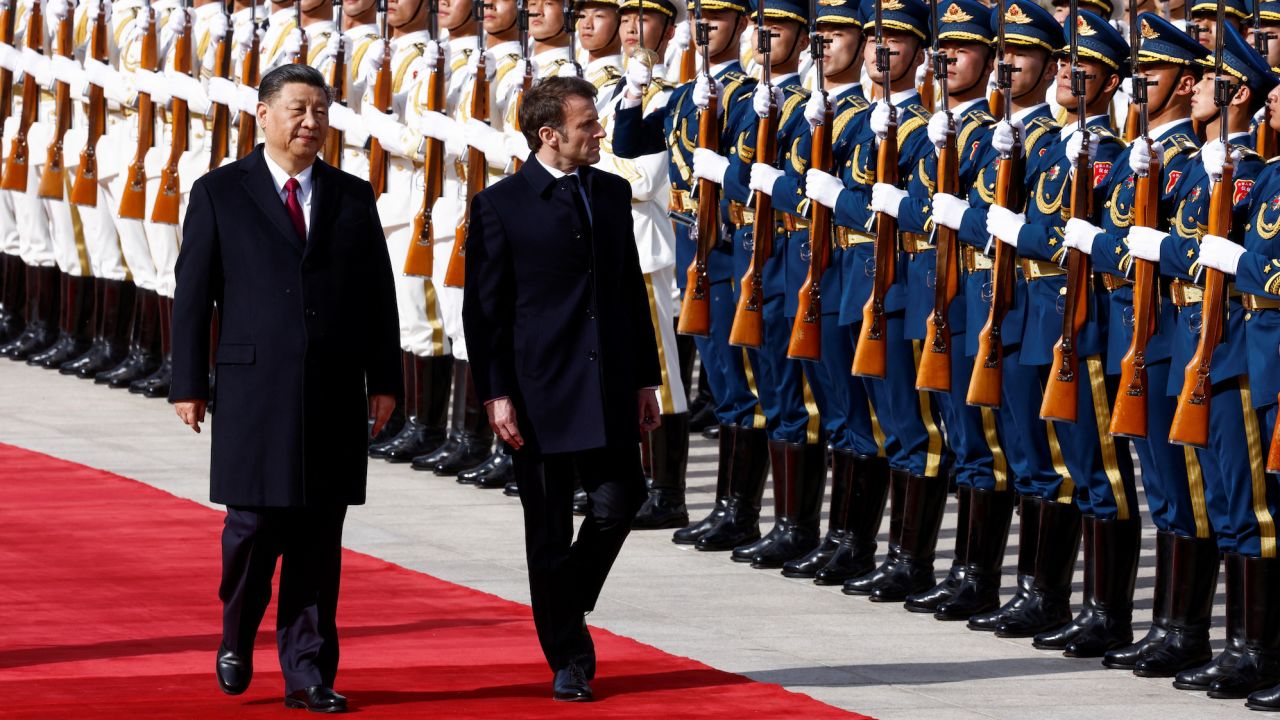

Yet this week in Beijing, French President Emmanuel Macron stood next Xi – who has not condemned Vladimir Putin’s war and doubled down on China and Russia’s “no-limits partnership” – and said “I know I can count on you to bring Russia to its senses, and bring everyone back to the negotiating table.”

Relations between China and the EU have been on a strange journey over the past decade. While an investment deal was struck in 2020 after years of negotiations, it is currently on ice, in part because of political differences – the EU has called China a “system rival” – but also because the Chinese government sanctioned European Parliament members after they criticized China’s treatment of Uyghur Muslims.”

Things have been frosty ever since and the lack of personal contact during the pandemic didn’t help.

This caused great upset to some EU members, who see good economic relations with China as essential to the bloc’s ambition to become a major geopolitical player.

“Strategic Autonomy”, an ugly Brussels term that refers to the EU having an independent geopolitical policy, relied in part of the EU being able to become a third power and not get squashed between the US and China. However, the China hawks, typically in the east of the bloc, have always been skeptical of anything that puts clear water between Europe and the US, who they see as the ultimate protectors of European territory through NATO.

A reluctant partner

Prior to the visit, Ursula von der Leyen, President of the EU Commission, had criticized China’s “becoming more repressive at home and more assertive abroad.” She said that it was clear to her that China had turned the page on its reform period and that national security now trumped and international cooperation: China is seeking to reshape the global order in a way that puts China at the center.

However, she said that these were not reasons for European to walk away from China, but to reduce any risk in their partnerships, rather than decouple from China, as the US seeks to.

The European Union, often criticized for its approach to international affairs when injustice runs directly into its economic ambition, has been far harder on Russia than expected. Through a series of sanctions and coordinated military aid, Brussels has pleasantly surprised diplomats and officials in other supranational institutions like NATO and the UN.

But the EU has declined to mete out similar punishment to Putin’s most important friend. The Ukraine crisis has forced many European officials to – in some cases reluctantly – conclude that their relationship with China might be more important now than it was before.

One European diplomat explains why it’s not possible to take a hard, US-style line of decoupling from China.

“We are not in a position geographically, economically or strategically to do what the US is doing. We cannot move away from both Russia and China at the same time,” the diplomat told CNN.

One example: “Sanctions against Russia increased energy prices. Our goal is to transition from Russian gas to renewable. A big part of that quickly is getting hold of cheap solar panels. Who makes cheap solar panels? China. We cannot shut out our original energy source and our new one at the same time,” the diplomat adds.

A second diplomat explained that while “no one is naive and thinks we should open the flood gates to Chinese technology,” most have accepted that “if we are to achieve our long term goals, including becoming a geo-political player who can hold influence over China, we need a strong economy. Our geopolitical value is nothing if our economy is struggling.”

‘China needs the EU’

Officials in the Commission paint a slightly less stark picture.

“Yes, there are things we cannot do without China, especially on climate change,” a senior Commission official tells CNN. “But China needs the EU more than it needs Russia,” they claim.

The official says that in the view of the Commission, Beijing’s support of Russia is more about appeasing the Chinese domestic audience in the short term by supporting a non-Western, non-NATO ally. They believe that China’s long-term thinking plays into the West’s hands more than it does Moscow’s.

“China’s power lies in its economy. It does more business with the EU than it does with Russia. They have seen what we were happy to do in terms of sanctions on Russia and don’t want that for themselves. China also wants to be seen as a responsible global power, not interested in upending the world order. This combination of factors creates an opportunity for us,” the official continues.

It’s a very optimistic view. Member states, including those who have historically taken a softer view on China like France and Germany, are more cautious than they’ve been for years.

“We have a problem with Russia that we will have for generations. If we have a problem with China at the same time, that is something we cannot geopolitica’ruly handle,” a government official of an influential EU member state told CNN. “Everyone is supports Macron’s trip and agrees we need to fix relations with China, but we are nervous about where it all ends and what China does in the context of Ukraine.”

The traditional China hawks within the EU share these concerns, but have equally been convinced that Europe cannot simply walk away from Beijing at the same time it does so from Moscow.

CNN spoke to diplomats from three of the most hawkish states.

Their main observations were that diplomatic lines with China must remain open, but with the express understanding that China could still get directly involved in the war. They say every effort must be made to discourage China from crossing the red line of arming Russia, that Europe must lead the dialogue and make sure engagement stays on European terms.

They also described fear that asking China to act as a peace broker between Ukraine and Russia gifts Beijing a propaganda coup where it can act as a player in European security with the EU’s blessing.

Alicja Bachulska, a policy fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations, told CNN that there is a window of opportunity for Europe to reshape its economic relationship with Europe.

“We don’t have to just sit down and accept China has more power than Europe. While it will be very difficult to persuade China to change its position on Ukraine, economic engagement with Beijing is still a must for the EU. But while we do that, we must also diversify our economy so we are less reliant on China.”

Alexander Stubb, the former Prime Minister of Finland, believes that “Russia’s attack on Ukraine marks the end of the post-Cold war era and the beginning of the crafting of a world order,” and that if Europe wants to play an important role in it, that “means staying as close to the US as possible, but not decoupling with China.”

Ever since Putin invaded Ukraine, the West’s largely coordinated response raised questions about a return to the US-led world order. But old questions about China have not gone away. And for Europe, the question of where it places itself in a multi-polar world has become more complicated and carries more risk than ever.