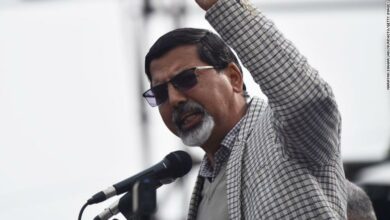

Ahmed Shafiq, former presidential frontrunner and Hosni Mubarak’s last prime minister, is back in the headlines. He was referred to criminal court Tuesday on charges related to facilitating the sale of the Kabreet land, an area overlooking the Great Bitter Lakes, near the Suez Canal.

Osama al-Saiedy, the investigative judge appointed by the Justice Ministry on the case, told Reuters the accusations include profiteering, forging official documents and squandering public funds.

While filled with legal loopholes, the case is also raising questions about being politicized, with Shafiq representing an important opposition pillar to his former adversary in the presidential race, President Mohamed Morsy, and his group, the Muslim Brotherhood.

The history of the case dates back to last May, when Essam Sultan, former MP and vice president of the moderate Islamist Wasat Party, filed a report to former People’s Assembly Speaker Saad al-Katatny, accusing Shafiq of squandering public funds. According to Sultan, the report included official documentation that would prove Shafiq — as head of the Cooperative for Construction and Housing of Air Force Pilots in 1989 — sold 40,000 meters of Kabreet land to Mubarak’s sons at a price lower than that offered to other members of the cooperative who acquired the land during the mid-1980s.

Even though other reports were filed against Shafiq accusing him of corruption during his time as civil aviation minister, this case seems to be heading in a different direction. After Katatny referred the case to Public Prosecutor Abdel Meguid Mahmoud, Shafiq entered a fierce media war with Sultan in parallel with the first round of the presidential election in May.

This was followed by a period of silence that left people under the impression that the case was closed and that the accusations were not based on solid evidence.

After Shafiq lost the presidential election and left the country to visit the United Arab Emirates, the case came back into the spotlight and its legal procedures were accelerated. The investigations ended with the corruption accusation against Shafiq, along with Nabil Shokry, former lieutenant and head of the cooperative at the time the deal was implemented, and three other air force officers.

Law experts see in the acceleration of the case an indication that a political factor is at play.

Ahmed Fawzy, human rights lawyer and secretary general of the Social Democratic Party, says it is illegal to refer Shafiq and his former colleagues to a civil court because Article 8 of Military Judiciary Law states that only military prosecution is allowed to investigate corruption accusations against former or current military personnel.

“The sequence of events in the case, and the fact that the general prosecutor did not refer it to military court, both its investigative and judicial branches, indicate a clear desire on the side of the political leadership to keep it in the civil court to guarantee no sympathy from the military,” argues Fawzy. “Unfortunately, officials in Egypt are always held accountable after they leave their positions, and corruption is later used to settle political disputes.”

The story

In 1985, the cooperative, a civil association that members of the same profession form with the state’s approval, bought the Kabreet land. According to its charter, all current and retired officers and their families are entitled to the privileges offered by the cooperative.

Playing its role, which is acquiring state land and selling it to its members with no profit, the cooperative justified buying this land because of its proximity to the airport. The land was formed during the reconstruction of the Suez Canal following its reopening in 1975, when land appeared inside the Great Bitter Lakes, surrounded by water from three sides.

Shokry, the fourth defendant in the case, says the land was bought from the governorate of Suez after the Suez Canal Authority and the General Authority for Fish Resources Development said they did not need it.

He says 64 members of the cooperative acquired lands in 1958. Seventy-three pieces of land were allocated to members between 1985 and 1989; three acquired land in 1987, and four — including Gamal and Alaa Mubarak, the former president’s sons — acquired land in 1989.

Conflicting accusations

In his first TV appearance on an Egyptian channel after losing the presidential election, Shafiq told Dream TV Saturday that Sultan’s allegations that he sold the land to Gamal and Alaa Mubarak at low prices were “absolutely false.”

At a press conference last May, Sultan said he had documents proving that Shafiq sold a total of 40,000 meters to Gamal and Alaa Mubarak in 1993, at a price of 75 piasters per meter. Sultan said he discovered, through the High Committee for Land Appraisal, which is affiliated with the Agriculture Ministry, that the price of a meter at this time was actually LE8.

“I understand that the cooperative allocates land to young pilots with an average income, but to do it for the president’s sons and at a cheap price — this is wasting public funds,” Sultan said.

On the other hand, Yehia Kadry, Shafiq’s lawyer on the case, says that, as the treasurer of the cooperative at the time the land was bought in 1985, Shafiq handled all the financial transactions of the cooperative. Hence, he would have known the cooperative had signed a contract with the Suez Governorate that year pricing the land at 59 piasters per meter, and that the land was allocated to members at this price.

“There is an important point that demonstrates my client’s innocence, which is that there are two kinds of contracts: the allocation contract, which the buyer makes with the cooperative at the time of land acquisition, and the sale contract, which is made when the buyer intends to build,” says Kadry.

Kadry says the price listed in the allocation contract is the preliminary price, which is 59 piasters — a sum that goes up in the sale contract when the buyer decides to build on the land.

He adds that the Mubarak brothers paid the difference between the price of 59 piasters per meter in the allocation contract and the LE6 for the 40,000 meters in the sale contract.

During the prosecution’s investigations, Gamal confirmed he and Alaa paid the difference, in addition to a surplus of LE127, when they made the sales contracts in 1993.

The Public Funds Investigative Authority also accused the defendants of adding 10,000 of the 40,000 meters in question with no legal basis.

Shafiq’s lawyer and Shokry, however, say both were aware of the allocation of the additional 10,000 meters, which were meant for the presidential guard, which was expected to go there when the president visited his sons.

“The 10,000 meters were included in the payment and we added them to the contract in case there was a need for a building for the presidential guards. This is a routine procedure,” Shafiq said during his TV appearance.

Shafiq’s fate

Since last August, Shafiq has been put on the airport surveillance lists, based on a public prosecutor call. Legal experts predict that if he is found guilty, he could serve a jail sentence of 10 to 15 years.

Kadry speculates that this might be the reason behind Shafiq staying in the Emirates and that the case would be heard in absentia. He denies reports that the public prosecutor has issued a warrant to Interpol to arrest him and bring him back into the country. Egypt shares an extradition agreement with the Emirates, based on which Shafiq could be arrested, returned to Cairo and kept in detention.

But Fawzy doubts this will happen.

“There needs to be political will for this scenario to take place. The Emirates had good ties with Mubarak and hence won’t extradite his associate that easily,” he says.

Fawzy adds that there are indications that Shafiq is in a politically precarious position, with his alleged military backers facing corruption charges themselves.

This week, a report accusing former Armed Forces chief of staff Sami Anan of graft charges was transferred to the military prosecutor by the public prosecutor. Similarly, a report on illicit gains by former defense minister and head of the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces Hussein Tantawi was also referred to the military prosecutor.

The referrals follow Morsy’s decision to send both men to retirement and replace them with a younger rank of officers.

“While Anan and Tantawi are being referred to military prosecution, which is the normal path for military officers, the development of Shafiq’s case is indicative of the fact that he is being politically punished, not criminally. His referral to a civil court is in violation of the law,” says Fawzy.